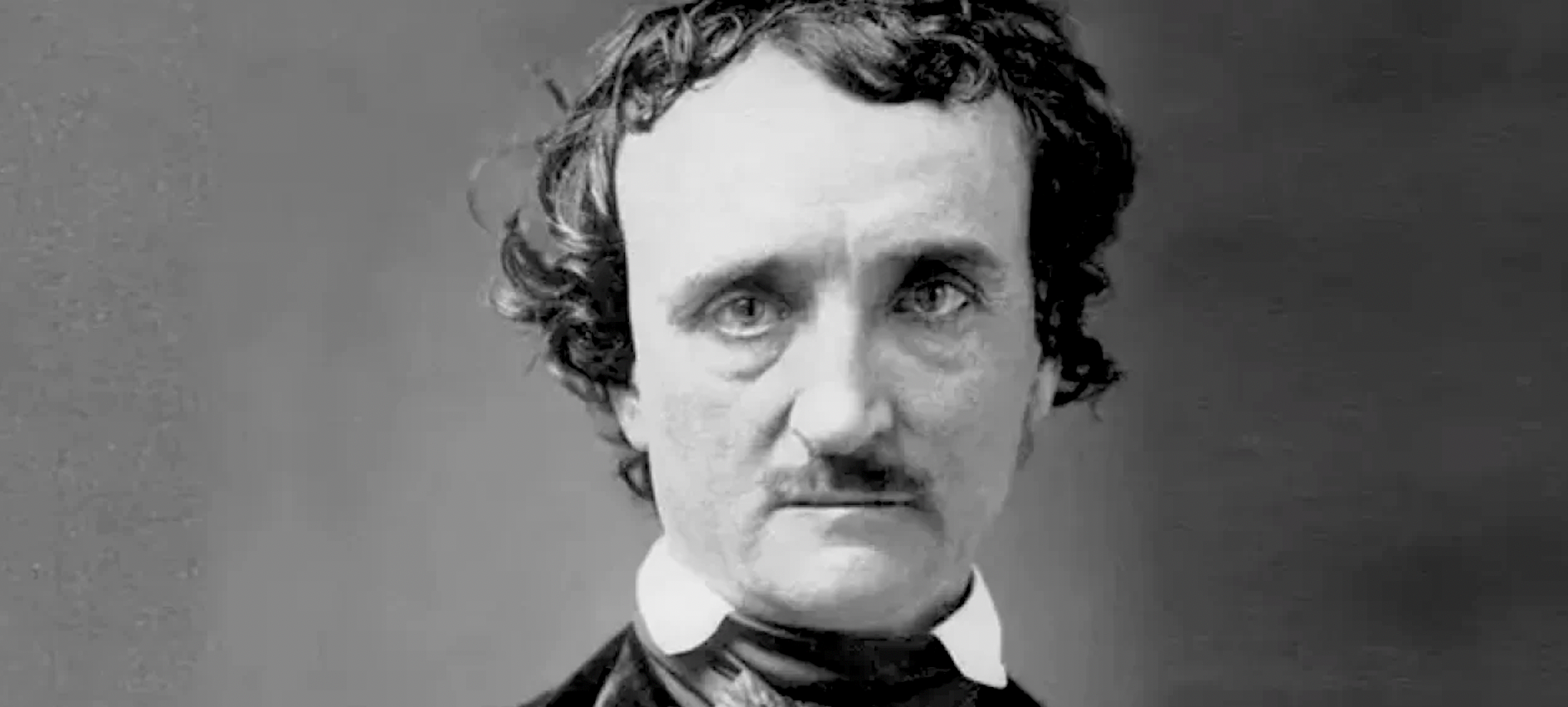

On May 3, 1841, Edgar Allan Poe, a thirty-two-year-old editor at Graham’s Magazine in Philadelphia, penned a request to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Smith Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard University. Two years Poe’s senior, Longfellow was established in an academic career and already had achieved renown as a poet, translator, and author of travelogues and romances. Ambitious and poor, Poe was hoping to make his literary reputation and support himself as an editor and tastemaker. To impress the professor of modern languages, Poe self-consciously sprinkled his entreaty with French phrases and flattered him with compliments:

DEAR SIR—Mr. George R. Graham, proprietor of Graham’s Magazine, a monthly journal published in this city and edited by myself, desires me to beg of you the honor of your contribution to its pages…I have no reason to think myself favorably known to you; but the attempt was to be made, and I make it.

I should be overjoyed if we could get from you an article each month, either poetry or prose, length and subject à discretion. In respect to terms, we would gladly offer you carte blanche; and the periods of payment should also be made to suit yourself.

In conclusion, I cannot refrain from availing myself of this, the only opportunity I may ever have, to assure the author of the “Hymn to the Night,” of the “Beleaguered City,” and of the “Skeleton in Armor,” of the fervent admiration with which his genius has inspired me….

With the highest respect,

Your obedient servant,

Edgar A. Poe

Longfellow turned down the request. In a noncommittal yet gracious response, he conveyed to Poe his own compliments:

May 19, 1841

I am much obliged to you for your kind expression of regard, and to Mr. Graham for his very generous offer, of which I should gladly avail myself under other circumstances. But I am so much occupied at present that I could not do it with any satisfaction either to you or to myself. I must therefore respectfully decline his proposition.

You are mistaken in supposing that you are not “favorably known to me.” On the contrary, all that I have read from your pen has inspired me with a high idea of your power, and I think you are destined to stand among the first romance-writers of the country, if such be your aim.

The two writers never met, and this exchange marked the beginning and end of their correspondence. Nevertheless, their names have been linked in the annals of American cultural history because of Poe’s literary attacks against Longfellow four years later in 1845, which Poe titled the “Little Longfellow War.” Poe’s “War” was an unprovoked aggression against one of the most beloved figures of the New England literary establishment, outraging Longfellow’s friends and fans. Chief among the contemporary writers who responded in Longfellow’s defense was someone who referred to himself as “Outis,” Greek for “nobody.”

The year after his request to Longfellow and Longfellow’s polite refusal, Poe began to sharpen his steel for his Little Longfellow War. In the March 1842 issue of Graham’s Magazine, Poe published a negative review of Longfellow’s Ballads of the Night, a collection of original poems and translations. Longfellow’s translations, Poe claimed, failed to do justice to the author or translator, but Poe reserved his most scathing criticism for Longfellow’s own poems, basing his disapproval, as he would again in the “Little Longfellow War,” on theoretical reasoning: “Mr. Longfellow’s conception of the aims of poesy is all wrong,” he wrote, “and this we shall prove at some future day.”

Three years later, in January 1845, now living in New York and reviewing Longfellow’s The Waif in the Daily Mirror, Poe revised his conception of Longfellow as a didactic naif who wrote “brilliant poems—by accident” to accuse him of that most serious of literary crimes—plagiarism: “We conclude our notes on the ‘Waif,’ with the observation that, although full of beauties, it is infected with a moral taint . . . somebody is a thief.” Poe accused Longfellow not of copying others’ words verbatim, which is our contemporary understanding of plagiarism, but of appropriating others’ ideas, meters, rhythms, and images. Longfellow, he charged, was guilty of “the most barbarous class of literary robbery; that class in which, while the words of the wronged author are avoided, his most intangible, and therefore least defensible and least reclaimable property is purloined.”

Two months later in March, now editing the New York-based Broadway Journal, Poe took advantage of his position to expand his charges of plagiarism against Longfellow. His elaboration of this “large account of a small matter” filled the pages of the Broadway Journal for six consecutive weeks, from March 1, 1845, to April 5, 1845. Poe claimed that he was writing in response to several of “Longfellow’s friends,” who had sent protests to the Daily Mirror, defending Longfellow against Poe’s attack on The Waif. According to Poe, Outis was the most persistent of the group, and Poe reproduced his long essay verbatim from the Daily Mirror to the Broadway Journal, prefacing an even more lengthy response. Outis asked:

What is plagiarism? And what constitutes a good ground for the charge? Did no two men ever think alike without stealing one from the other? or, thinking alike, did no two men ever use the same, or similar words, to convey the thoughts, and that, without any communication with each other? To deny it would be absurd.

Outis proceeded to give the example of “an anonymous writer, observing a January thaw…Every tree is a diamond chandelier.” Supposing this anonymous writer put his description in a drawer. Soon after, there appeared in a publication a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier that described a similar scene, “The trees, like crystal chandeliers.” The similarity was not a theft, but a coincidence. “Images are not created, but suggested,” reasoned Outis. “And why not the same images, when the circumstances are precisely the same, to different minds?”

While praising Poe’s poem, “The Raven,” as “a remarkable poem… of uncommon merit,” Outis maintained that, given his definition of plagiarism, Poe was himself guilty of this charge. Outis referenced “an anonymous poem of five years ago, entitled ‘The Bird and the Dream,’” wherein he found no less than fifteen “identities” with “The Raven.” Yet Outis would not charge Poe with plagiarism. On the contrary: “I have selected this poem of Mr. Poe’s, for illustrating my remarks, because it is…remarkable for its power, beauty, and originality.” Outis concluded:

Though acquainted with Mr. Longfellow… I have no acquaintance with Mr. Poe. I have written what I have written from no personal motives, but simply because, from my earliest reading of reviews and critical notices, I have been disgusted with this wholesale mangling of victims without rhyme or reason. I scarcely remember an instance where the resemblances detected were not exceedingly far-fetched and shadowy, and only perceptible to a mind pre-disposed to suspicion, and accustomed to splitting hairs.

Outis’s epistle galvanized Poe to a counter-response of nearly fifteen thousand words, “A Continuation of the Voluminous History of the Little Longfellow War,” published in the Broadway Journal the following week on March 15. He took the opportunity to launch into a long and detailed analysis and comparison of his use of poetic meter and rhyme in “The Raven.” One by one, he refuted each of the “identities” found by Outis, claiming his arrangement of poetic meter was unique. The tone of his rebuttal to Outis escalated, and it is hard not to read in it a dominant note of (to use a term that Poe might have employed himself) ressentiment. Amounting to more than resentment, ressentiment is a deeper grievance, which often—as in this case—has its basis in disparities of wealth and social class. He wrote:

The plagiarist is either a man of no note or a man of note. In the first case, he is usually an ignoramus, and getting possession of a rather rare book, plunders it without scruple, on the ground that nobody has ever seen a copy of it except himself. In the second case (which is a more general one by far) he pilfers from some poverty-stricken, and therefore neglected man of genius, on the reasonable supposition that this neglected man of genius will very soon cut his throat, or die of starvation, (the sooner the better, no doubt,) and that in the meantime he will be too busy in keeping the wolf from the door to look; after the purloiners of his property—and too poor, and too cowed, and for these reasons too contemptible, under any circumstances, to dare accuse of so base a thing as theft, the wealthy and triumphant gentleman of elegant leisure who has only done the vagabond too much honor in knocking him down and robbing him upon the highway.

While Poe did not accuse Longfellow of plagiarizing him specifically, he considered himself a “neglected man of genius,” while casting Longfellow as a “wealthy and triumphant gentleman of elegant leisure.” Born to a prominent Portland, Maine, family that could trace its origins back to Mayflower passengers John and Priscilla Alden, Longfellow enjoyed a secure background and a fortunate upbringing. One grandfather was a Revolutionary War hero, the other grandfather a prominent judge, and his father was a prosperous attorney who had represented his Maine district in the House of Representatives. Longfellow had been privately tutored as a boy and completed his education at Bowdoin College, where his father was one of the founding trustees, Nathaniel Hawthorne one of his classmates, and Franklin Pierce in the class ahead of him. With his knowledge of French, Spanish, Italian, and German, his years of European travel, his academic sinecure at Harvard, and his comfortable existence in beautiful, historic Craigie House, in rooms once occupied by George Washington, Longfellow enjoyed a life of privilege that was everything that Poe’s life was not.

Orphaned at an early age, disowned by his guardian whose fortune he had expected to inherit, forced to withdraw from the University of Virginia after one year because of debts, susceptible to alcohol, Poe lived a life of turmoil, frequently changing lodgings and jobs, nearly always in poverty and emotional upheaval.

While Poe did not accuse Longfellow of plagiarizing him specifically, he considered himself a “neglected man of genius,” while casting Longfellow as a “wealthy and triumphant gentleman of elegant leisure.”Nevertheless, Poe considered himself to be Longfellow’s intellectual superior. Poe was a self-proclaimed literary theoretician, devoted to reason, logic, and rigor, an autodidact who cleaved to high, self-imposed standards. An intellectual outside of the academy, Poe had all the brilliance and dangerous notions of a man who had developed his ideas in relative isolation. In contrast, Longfellow, despite his formal education, was a dreamy popularizer and a borrower from other cultures, whose poetry inhabited moods and tales rather than ideas, and who showed little interest in literary theories.

Poe couldn’t forgive Longfellow for his popularity—his embrace by the literary and academic establishment and the less sophisticated public, who were reassured and comforted by Longfellow’s didacticism, even as they were in thrall to the music of his verses and his narrative skills. In contrast, Poe depicted himself as an independent voice of poetic principles, railing against charlatans like Longfellow and their cowardly, anonymous defenders like Outis.

In the 170 years since Poe published this diatribe, the identity of Outis, whom Poe compared to a bullying mob, has been the subject of speculation among scholars, who have attempted to identify various contemporary figures as Poe’s shadowy adversary. None of the candidates, however, has earned any sort of universal acceptance. Attacking Poe was one of the surest routes to popularity in most of the literary circles of the time, yet no writer stepped forward to take credit for Outis, and Longfellow himself professed ignorance on the matter, although Outis claimed to be a friend of his.

So long after the fact, the person of Outis remains a mystery, and Poe’s motives in initiating and prolonging the controversy a matter of debate. Was Poe exhibiting more of his out-of-control, crazy behavior in promulgating the “Little Longfellow War”? How seriously should we take his charges? Were his literary criticisms credible, if cranky?

In his long rebuttal to Outis, Poe offers a clue to his motivations when he defends himself against the charge of unpopularity:

In one year, the circulation of the “Southern Messenger” (a five-dollar journal) extended itself from seven hundred to nearly five thousand,—and that, in little more than twice the same time, “Graham’s Magazine” swelled its list from five to fifty-two thousand subscribers.

Was the “Little Longfellow War” a publicity stunt instigated by Poe in an effort to try to increase the circulation of the Broadway Journal, as he had with previous periodicals? In Poe’s day, as well as in ours, controversy sold copies, and Poe’s quarrel with Longfellow was not the first nor the last literary feud that he provoked for the sake of boosting sales. More than one critic has suggested that Outis was none other than Poe himself. The inventor of the modern detective story, Poe enjoyed mysteries and games. As in “The Purloined Letter,” he hid his clues in plain sight. In an unpublished essay, “The Reviewer Reviewed,” Poe, writing under the name of Walter G. Bowen, attacked his own writings in a tone reminiscent of Outis.

All his life, Poe delighted in hiding behind multiple identities and inventing adventures and escapades for himself. In his life and his art, he was a master manipulator. While purporting to criticize Poe, Outis flattered him, alluding to his “beautiful and powerful poem” and playing the same word game with Poe’s name as Poe had done earlier: “Mr. EDGAR A. POE. (Write it rather EDGAR, a Poet, and then it is right to a T.”

Outis was a useful invention for Poe, giving him an adversary in a public forum whom he could manipulate to his heart’s content. Far from a “pathetic wreck” on the verge of mental collapse, “thoroughly embarrassed” and “driven to his wit’s end to vindicate himself,” as his biographer Sidney Moss described him, Poe was an obsessive, self-promoting schemer, with a rapier-sharp wit, a love of intrigue, and an enjoyment of the joke that turned on itself like a Mobius strip. Indeed, these are the aspects of his character that speak so forcefully to our present day.

“Outis… has praised me even more than he has blamed,” Poe reminded us, should we prove too obtuse to perceive it for ourselves. Magnanimously, he avowed that he bore Outis no ill will, for Outis had (as was intended) afforded him a valuable opportunity:

In replying to him, my design has been to place fairly and distinctly before the literary public certain principles of criticism for which I have been long contending, and which, through sheer misrepresentation, were in danger of being misunderstood.

Throughout its six-week duration, the “Little Longfellow War” was a one-sided skirmish. If Poe had hoped to provoke Longfellow’s response in his own defense, he did not succeed. When beset by critics, both at this time and throughout his life, Longfellow sheathed his pen. That is not to say that Longfellow was not upset by Poe’s attacks. During that spring of 1845, he confessed privately in his journal that he “damns censorious Poe.” He could have been speaking of Poe when he wrote, “A young critic is like a boy with a gun; he fires at every living thing he sees. He thinks only of his own skill, not of the pain he is giving.”

Perhaps it was precisely because Longfellow was so pained by negative criticism—Poe’s and others’—that he made efforts to protect himself from its effects by creating a mental distance. In his Table Talk, a collection of his notes and aphorisms published posthumously, he noted, “A great part of happiness of life consists not in fighting battles but in avoiding them. A masterly retreat is in itself a victory.”

Longfellow could afford to ignore his critics. No other American poet, before or since, has enjoyed such great popular success or tremendous sales. Income from the sales of his poetry enabled Longfellow to retire from his Harvard professorship in his forties. Of greater concern to him than harsh criticism was the need for stricter international copyright law to prevent the piracy of his works overseas. He urged his close friend Congressman Charles Sumner to introduce this legislation, an effort in which he was joined by another close friend, Charles Dickens, who also suffered from copyright piracy. Samuel Longfellow, his brother and biographer, estimated that for want of an international copyright, the poet forfeited forty thousand dollars in income—in nineteenth-century dollars, a fortune.

For Poe, the point was not the justice of his accusations against Longfellow, but the incitement of a controversy and the attendant publicity.Plagiarism in the mid-nineteenth century had a different meaning than today. Then plagiarism might refer to any literary borrowing, whether conscious or unconscious. In this broad sense, every writer is a plagiarist, but not every plagiarism is a crime. Critics could not agree if ideas were copyrightable. Could an idea be attributed to a single author, and how specific or original did the idea have to be to “belong” to the author? Plagiarism scholar Sandi Leonard has suggested that once stricter international copyright laws were established, the conception of plagiarism began to shift to a demonstrable notion of copying verbatim, with intention. The establishment of a legal standard redefined our understanding of plagiarism, rather than the other way around.

For Poe, the point was not the justice of his accusations against Longfellow, but the incitement of a controversy and the attendant publicity. The wrong that he was seeking to redress was not literary theft, but the unfairness of life that decreed that Longfellow was rich and successful, and he was poor and obscure. Nevertheless, the charge of plagiarism was more than a convenience for Poe. Themes of plagiarism, influence, doubling, and imitation, which penetrated deeply into Poe’s psyche, are expressed in his troubling fictions and colored all of his literary and professional relationships. Poe’s hypersensitivity to this subject and the complexity of his twisted, contradictory responses continue to exert their fascination, offering insight into the demonic psyche, the individual in extremis.

Balance, proportion, and moderation were Longfellow’s qualities. But Longfellow, a lifelong student and translator of Dante, recognized a soul in torment, and he pitied Poe the man while appreciating his poetic talents. Author and critic William Winter (1836–1917), who befriended Longfellow during his Harvard days in the 1850s until Longfellow’s death thirty years later, recalled that the older poet kept a volume of Poe’s poems on his table, singling out for special praise Poe’s late poem “For Annie.” (When asked to recommend an epitaph for Poe’s 1857 memorial, Longfellow chose the line, “The fever called ‘Living’ / is conquered at last” from “For Annie.”)

After Poe’s death, Longfellow provided financial support to Poe’s aunt and mother-in-law, Maria Clemm. Taking the long view, he said to Winter, “I never answered Mr. Poe’s attacks and I would advise you now, at the outset of your literary life, never to take notice of any attacks that may be made upon you. Let them all pass. My works seemed to give him much trouble, first and last; but Mr. Poe is dead and gone, and I am alive and still writing—and that is the end of the matter.”

*

Author’s Note: I am grateful to the Edgar Allan Poe Society for making Poe’s criticism, along with all of his writings, available digitally