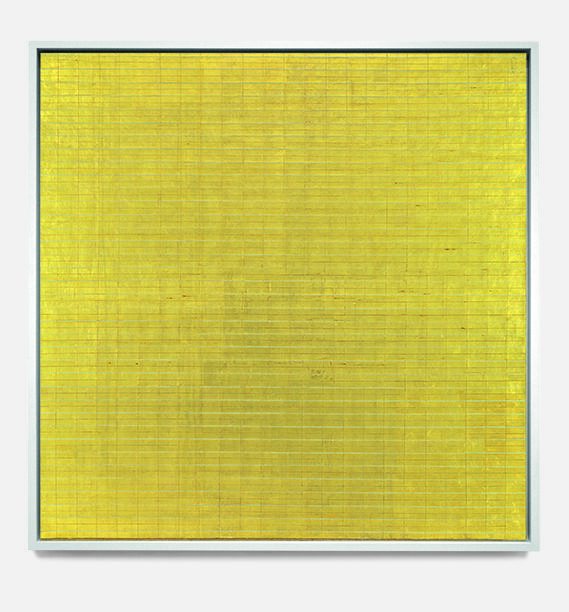

Featured image: “Close Up of Friendship” by Agnes Martin © Agnes Martin Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

On a cold day deep in the pandemic I took the Q train from Brooklyn to see the Agnes Martin painting Friendship (1963) at the Museum of Modern Art. Friendship is a six-by-six-foot square, gold leaf grid. The surface shimmers and jumps. I think of mosque ceilings, of God’s geometry. I sense something vast inside the painting, an energy with no beginning or end. Martin used an ancient technique called sgraffito, scratching into the barely dry gold paint to expose the red paint underneath. The grid is mathematical, but also human in its slight off-ness, its many small imperfections. Before it, I feel small but not diminished. A smallness that I sometimes feel inside a great snowstorm, a smallness that places me back into the grid of the world’s infinite living things.

Martin recalls in many interviews that in Saskatchewan, where she grew up, the land was so flat, “you could see the curvature of the earth. When the 9am train left the station, it was still leaving at noon.”

On my next visit to MoMA, the docent lets me sit on the floor before Friendship. In the days between my first visit and this one I’ve read about Martin’s life. How friendships were complicated for her—her need for people, but also how easily they could overwhelm her. After she left New York City in the late 60s, Martin wrote to a friend, “I do not think that there will be any more people in my life.” When, years later, feminist Jill Johnston visited Martin in New Mexico, Martin felt Johnston’s nightmares were infiltrating her own head. The gold paint curling up around the thin lines have a broken- skin-like quality, a scratch, and underneath the hint of blood.

In a letter to a former lover Martin wrote, “I have tried existing, and I do not like it. I would like to give it up. Please pretend that I am dead.”

Friendship by Agnes Martin © Agnes Martin Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Friendship by Agnes Martin © Agnes Martin Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Between the second and third visit, Friendship begins to appear in my mind at random times throughout the day. To me, a minister’s daughter whose main icon both at home and in church was the cross, Friendship is a grid made up of hundreds of tiny crosses. Not fixed symbols of suffering or redemption but, as Simone Weil described them, the cross—a conduit that explores struggle.

Art critic Rosalind Krauss has described the grid as a paradox that allows two realms of “paralogical suspension”: “The grid’s mythic power is that it makes us able to think we are dealing with materialism (or something like science or logic) while at the same time it provides us with a release into belief (or illusions or fictions).”

On my fourth visit to Friendship, the way is now familiar. I move easily down Broadway to 53rd Street, then left toward MoMA. The city is uncannily empty, the street a grid of closed restaurants and empty office buildings. Inside MoMA, I find my way to the fourth floor, through the maze of gallery rooms to the permanent collection installation Touching the Void. The new docent will not let me sit on the floor, but suggests I go back downstairs to the front desk and ask for a folding chair. And so I do, sitting like a tailgater in a stadium parking lot contemplating Friendship.

“I am intrigued and touched,” wrote the sculptor Richard Tuttle, “by a quality of her [Martin’s] painting that is not real, which may be related to such things as phantoms and mirages. It moves from here to there.” The gold surface rises, then flattens, like wind in a wheatfield, or the pattern my petting hand makes in my cat’s fur. After nearly an hour, suddenly, the painting closes to me. I feel dismissed. I stand and fold up my chair. Just outside the gallery doorway, I see, from the side of my eye, Friendship shift like a school of tiny goldfish, each no bigger than a dust mite, all turning, changing directions, moving one way and then another.

“The path to an understanding of nothingness,” writes Robert E. Carter in his book about the philosopher Nishida Kitaro, “is the nothingness of poetic experience i.e. the self as pure awareness.”

*

Martin used a quote from Gertrude Stein’s poem “Idem the Same,” written for her longtime lover Alice B. Toklas, for the exhibition card of her 1967 show at Betty Parsons Gallery: “In which way are stars brighter than they are. When we have come to this discussion. We mention thousands of buds. And when I close my eyes I see them.” Jill Johnston has written that Martin was “a dead ringer” for Stein. Later in life Martin adopted Stein’s high bangs and close-cropped hairdo. Martin heard stories about Stein from both Betty Parsons and Mabel Dodge Lujan, who’d met the writer in Paris. One friend called Martin “a walking Stein seminar.”

At Coenties Slip, in downtown New York City, Martin and others, including Ellsworth Kelly and Robert Rauschenberg, had studios—a creative space art historian Jonathan Katz has characterized as a gay community. In the evenings the resident artists sometimes gathered, and Martin once gave a poetry reading from Stein’s erotic poem “Lifting Belly”: “Every night/Lifting belly again./It is a credit to me.” While we know Martin read Eastern texts and, later in her life, shopping bags full of mystery novels, Stein is the writer closest to Martin in both form and intent. In speech, Martin sometimes sounded like Stein: “I’m not a woman I’m a doorknob, leading a quiet existence.”

An early girlfriend of Martin’s, Krista Wilson, felt the artist was “very secretive” and “tremendously conflicted” about her sexuality. The only place Martin felt free was in the woods. Martin took Krista camping every weekend after they first met in the 1950s. “Camping,” Wilson said, “gets you into a lot of trouble!” Wilson wanted to live an out life with Martin. Agnes was certain that she could never be a successful artist if people knew she was gay. “I put it to her one time that Gertrude Stein was famous, and she wasn’t secretive.”

“The care with which the rain is wrong,” Stein writes in Tender Buttons, her celebration of lesbian domestic life, “and the green is wrong and the white is wrong, the care with which there is a chair and plenty of breathing.” And in a section called “Petticoat”: “A light white, a disgrace, an ink spot, a rosy charm.”

Stein was not interested in a forward-moving plot, but rather, like Martin, the eternal now. The continual present. While at Harvard, studying under William James, Stein and her lab partner did experiments that examined reality and consciousness. “They sought to find,” wrote John Malcolm Brinnin in his book The Third Rose, “the exact point at which the personality may be said to ‘split’ thereby releasing a secondary personality operating without discernible reference to the first.” Often Stein herself was the subject for free writing experiments. In one, Stein records her experience in the third person: “Strange fancies begin to crowd upon her, she felt that her silent pen is writing on and on forever.”

“To the extent that her painting can be called automatist, it can also be identified with unspoken and not fully articulated writing,” Nancy Princenthal writes in her biography of Martin. “It is a line of language, not in the sense of discrete meaningful words but as the minimal structure, the onward flow, of all rumination.”

“Words left alone,” writes Stein, “more and more feel that they are moving and all of it is detached and is detaching anything from anything and in this detaching and in this moving it is being in its way creating its existing.”

*

In the late 1960s, when Martin lived and worked in her studio at Coenties Slip, she was in a church one Christmas season, listening to Handel’s Messiah. “After three notes I zonked out, in a trance,” she told her art dealer Arne Glimcher. “I’ve been in many trances, you know. That’s how they put me away in Bellevue.”

Martin experienced fugue states, but also voices that no one else could hear, voices that could emanate from dogs, or houses. Krista Wilson told an interviewer that Agnes told her demons spoke to her and had come through the walls and taken her wallet. Her voices told her she could not own property. In a message to a friend, the photographer Donald Woodman, she wrote, “My voices have instructed me to tell you that we are moving to your land in Galisteo.”

Esmé Weijun Wang writes, in her book about her own schizophrenia, about how quickly a psychotic break can overtake her. “I turn my head and in a single moment realize that my coworkers have been replaced by robots.” It was not music but an episode of the science fiction television show Doctor Who that breaks reality for Wang. After Doctor Who is over, Wang asks her friend: “Did that happen someplace else?” Another schizophrenic writer describes how she disassociates: “Consciousness gradually loses its coherence. The me becomes a haze and the solid center from which one experiences reality breaks up like a bad radio signal.”

Passages from Martin’s own writing suggest a complicated and nuanced relationship to reality. “The silence on the floor of my house is all the questions and all the answers that have been known in the world.” And: “The sentimental furniture threatens the peace.” Objects freighted with memory can disorient Martin’s acute sensitivity. And she’s not wrong—the kitchen table in my house in Brooklyn belonged to a great-aunt, a woman whose loneliness can emanate, when I am susceptible, from the white enamel.

Objects freighted with memory can disorient Martin’s acute sensitivity. And she’s not wrong—the kitchen table in my house in Brooklyn belonged to a great-aunt, a woman whose loneliness can emanate, when I am susceptible, from the white enamel.White Stone (1964) at the Guggenheim is a tighter grid than Friendship. Pencil lines moving up and down and side to side make a grid of small squares, hovering above an expanse of mottled white. It has a depth and pull that Friendship lacks. White Stone hangs in a show entitled Marking Time: Process in Minimal Abstraction, a white painting among other white paintings.

But Martin’s painting, to me, differs dramatically from that of her peers. I feel I am staring at a sword rather than a work on canvas. “You can almost feel,” Buffalo-based painter Pam Glick told me, “Agnes trying to keep it together.” Glick admires Martin for bringing the mind into her painting. “They are as much about her mind, as the paint.” White Stone’s murky depths remind me of the river bottom where I swim in upstate New York. Slow motion. Lines of leaves buried in grey muck, the ancient seeded in the now. Nearby in the Guggenheim, the voice of Roman Opałka, the Polish painter of numbers one to infinity, emanates from his painting 1520432-1537871—a recording of him counting each digit in Polish, as he marks his canvas.

The charts W. E. B. Du Bois created in the mid-nineteenth century show the progress of African American life in the United States. These spirals, block prints, and lines in bright colors have an undeniable link to Abstract Expressionism. “These images,” write Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert in W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits, “anticipate the forms of ‘racial abstraction’ that would come to define social scientific, visual, and fictional representations of Harlem beginning in the 1920s.” In one chart, a black line climbs year by year up a grid, marking the value of Black-owned property. The chart is both diagnostic and holy, a visual representation of struggle and ascendency.

“Because of its bivalent structure,” Rosalind Krauss writes, “the grid is fully, even cheerfully schizophrenic.”

Rather than discount her voices, Martin seems to have worked with them. Current therapies for schizophrenics can include negotiations with voices rather than medicating them. T. M. Luhrmann, a psychological anthropologist who started the Hearing Voices Movement, helps patients come to terms with their inner voices. She explains that how a person feels about their voices is culturally constructed. In Europe and America, we see ourselves as individuals motivated by a sense of self-identity. In America particularly, voices are intrusions and a threat to our private world. In Africa and India, Luhrmann’s subjects were less frightened by voices; some even assumed they were ancestors instructing them in positive ways. If voices were addressed, directly and appropriately, Luhrmann found they eventually became less hostile: “The emotional pain carried by a voice must be acknowledged and understood before its ferocity can abate.”

Martin’s voices told her not to own dogs, so she raised chickens. They instructed her not to own property, so she built a house and studio on her friend Donald Woodman’s land. Woodman lived in a teepee on the same land, and for a time in the 1970s he and Martin were close. The Colorado State Hospital called Woodman when Agnes was admitted after having been found in the street disoriented and screaming at the top of her lungs. “Her relationship to her voices was a constant struggle,” Woodman wrote to me in an email, “to quiet them and allow her to focus on the inspiration for her painting.”

“Surely,” writes Douglas Crimp, “it is the turmoil away from which Martin turned . . . that constituted the tensions so many of us see in her paintings.”

“I am aware that the man who is said to be delusional,” writes R. D. Laing in his book The Divided Self, “maybe in his delusions is telling me the truth and this is in no equivalent or metaphoric sense, but quite literally and that the cracked mind of the schizophrenic may let in light which does not enter the intact mind.”

To let in light, to trap light, to, like a lantern, contain light, to hold light. To, as Hilton Als has written about Martin, “make mystery a solid object.”

*

“My paintings,” Martin said, “are about merging, about formlessness.” I wonder if Martin’s interest in formlessness may have come from her unique experience of reality, but also perhaps because she did not fit into traditional gender roles. Martin said she was not a woman; she was proud that “us Martins are military men,” and enjoyed being misgendered in restaurants by waiters. Martin was anti-domestic, living in her camper until she was nearly seventy. When asked about marriage and children she experienced not regret but relief. She tells an interviewer she believes in reincarnation: “I’ve had hundreds of children. This time I asked to be left alone.”

I wonder if Martin’s interest in formlessness may have come from her unique experience of reality, but also perhaps because she did not fit into traditional gender roles.Years before Judith Butler’s idea of gender performativity, Martin saw femininity as a burden. “The concept of a female sensibility,” she wrote, “is our greatest burden as women artists.” Martin recognized the energy women spent and wasted on propping up femininity, as well as the weight of domestic duties. She also co-opted traditional female symbols. Martin wrested the rocking chair, associated with grandmothers and elderly obsolescence, from the front porch and into a place of contemplation and inspiration. Likewise, in a photo taken by Mildred Tolbert in the late 1950s, Martin wears a striped apron with black piping. The apron, a housewife staple, is transferred from the kitchen into the archetypal realm of creativity, the artist’s studio.

Ann Lee, founder of the Shakers, also elevated domestic symbols as part of her theology. In one story, a follower in the midst of a religious crisis clings to the bottom of Ann Lee’s apron, wringing it in her hands. Eventually, Lee takes off the apron and gives it to the women as sign of both maternal and spiritual support.

Martin denied her paintings were in any way religious. She called the current religious landscape “messed up.” Still, release from materiality, a key religious tenet, is one of her aims. “These paintings are about freedom from the cares of this world,” Martin wrote, “from worldliness.”

The eleventh-century nun Hildegard of Bingen saw freedom in the regeneration of plant life. Her philosophy of viriditas, or “ever greening,” revolved around a generative force found in all the earth’s life, as well as in art, in poetry, in theology. Mary, for Hildegard, was the green branch, and Jesus the bloom. “Glance at the sun,” she wrote, “see the moon and the stars. Gaze at the beauty of the earth’s greening. Now think.”

*

In the Harwood Museum in Taos, New Mexico, I sit on a bench designed by Donald Judd and contemplate a sequence of Martin’s paintings from the 1990s. Early vaccination has landed me, to my delight, in the West, where the empty expanse of red earth covered in clumps of sage brush makes me feel exposed, but also somehow central, as if a great being has drawn a circle around me on their map. The seven paintings, horizontal stripes in white and pale blue, activate one after another. Their surfaces opening, flooding with subtle light. I take a photo with my phone of the palest painting, and send it to a friend, the Los Angeles–based painter Kevin Appel. I write that while these later line paintings are successful, they don’t move me the way the New York grids do. He replies: What’s crazy is how, using essentially the same elements, the late paintings are so different. I write that they are easier to access. Kevin: Yes. New York more laborious. In New Mexico she freed herself from labor. An aspect of freedom I had not thought of. Martin, her skills developing, gets to the effect she wants faster. Kevin brings in the metaphysical: More direct contact.

In her eighties, Martin, who struggled for equilibrium and peace throughout her life, would often say she “stayed above the line.” The lines in the Harwood paintings emote and tremble. They open up a passageway connecting this world with the next. Wang writes of how she uses a “lifeline” whenever she feels an episode coming on: “When a certain kind of psychic detachment occurs, I retrieve my ribbon; I tie it around my ankle. I tell myself that should delusion come to call, or hallucinations crowd my senses again, I might be able to wrangle sense out of the senseless. I tell myself that if I must live with a slippery mind, I want to know how to tether it, too.”

“To hold onto the ‘silver cord,’” Martin wrote, “the artist’s own mind will be all the help he needs.”

Upstairs at the Harwood, in a new room devoted to Martin’s early works, is a sequence of drawings, as well as Nude (1947), one of the few representational paintings Martin did not destroy, and Tundra (1967), the last work Martin painted before she left New York City in 1968. Tundra is no quick conduit; if it’s an escape hatch, it remains a secretive one. Six rectangular canvases form one large, loose grid. Smoky light floats up around the grey rectangles.

Martin painted Tundra at a time of uncertainty in her life. At fifty-five, she was about to lose her beloved high-ceilinged, light-filled Coenties Slip studio. She’d broken up with her girlfriend Lenore Tawney, and her friend Ad Reinhardt had died suddenly of a heart attack. Her most recent show at Betty Parsons Gallery had gone well, and she felt pressure to join a commercial art world she distrusted. With money from a fellowship, Martin bought a truck and drove west, beginning a nomadic period that would last three years.

“My heart—I thought it stopped,” writes Amy Hempel, in her short story “In a Tub.” “So I got in my car and headed for God. I passed two churches with cars parked in front. . . . I thought about the feeling of the long missed beat, and the tumble of the next ones as they rushed to fill the space.”

*

“The best thing to do after you finish painting,” Martin said, “is to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge.”

I start at Coenties Slip next to the East River and nearby Wall Street. The sail factory that housed Martin and her contemporaries’ studios was torn down long ago. In its place there is now a Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Green glass is etched with lines from the letters of fallen soldiers. A passage reads: “One thing that is worrying me—will people believe me? Will they want to hear about it. Or will they want to forget the whole thing ever happened.”

From the slip I walk from Water, to Gold, to Pearl Street. A doorway in a cement wall opens to steps that lead up toward the Brooklyn Bridge. On the boardwalk, cars rush by on either side. Soon, I am high above them and even farther from the lapping and tumbling East River below. Wind whips my hair against my face. “Renunciation,” writes Jonathan Katz, “seems to have been Martin’s chosen form of self-expression.” She left Canada, she left New York City, she lived for decades in a camper, first on the road and later in New Mexico. She gave up romantic relationships. Using a box cutter, she destroyed works that did not please her, and then burned them in a yearly bonfire.

At the bridge’s high point, I look out toward the horizon. It’s a cloudy day, but the demarcation between water and sky spills white. Once when asked what she was painting, Martin replied, “I’m doing a river.” The horizon in New York City is harder to find than in New Mexico, but it still holds the wonder of the earth’s rotation, the reminder that day after day we fly through darkness, circling an all-encompassing light. I am the same age as Martin when she made Tundra. Like the concept of God, the painting is the last fixed point before she jumped. Numinous, but not necessarily positive, Tundra, like all Martin’s paintings, reminds this viewer of life’s sad grandeur and its relentless, ever-greening flow. The artist did not know then that, after a time of travel and aloneness, she would move into her longest and most productive period. As she entered her sixties, an age at which the culture tells women they are over, Martin had just begun.

____________________________________

From “Touching the Void” by Darcey Steinke, from Agnes Martin: Independence of Mind. Used with permission of the publisher, Radius Books. Text Copyright © 2022 by Darcey Steinke. Images © Agnes Martin Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.