Playing the End: Alice Austen on Writing Character Like an Actor

“We all have layers; we are all actors playing our parts.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Early on, a Cuban theater director gave me advice on writing characters I’ve never forgotten—

“Watch them,” she told me. “See what they do.”

I did. To my fascination, my characters began to take on lives of their own, seeming almost to write themselves. In Cherry Orchard Massacre (very loosely based on Chekhov’s play), I wrote a character called Boris, an audience plant whose cell phone would ring a lot. Boris was funny. Ruthless. Before I knew it, he’d hijacked the play, taken the actors hostage, and stepped in for the lead… after killing him.

An extreme example, sure, but theater is as alive as it is unpredictable. Take my first play—I wrote it on a pub bet with two actor friends who were looking for something to star in together. The play was produced, they weren’t cast—a perfect introduction to theater politics. I went on to become a playwright, another plot point I couldn’t have imagined.

I hadn’t studied theater. So I read plays. I watched plays. I workshopped colleague’s plays; they workshopped mine. The director of the Chicago playwrights theater took me under his wing and gave me his trademark scathing, kind feedback. “Make sure you don’t quote a writer in your play who’s better than you are.” Or “Don’t cast him—he has a face like a shovel.”

I grew to love theater: the tension of performance before a live audience, the way everything happens in the moment, the unexpected raw emotions that can emerge to enrich or disrupt. All this has influenced my novel writing. To me, a novel should be as exciting and unpredictable as a theatrical performance.

An actor must make illusion seem real. They must integrate layers of their own personality with those of their character and emerge on stage as one. It’s a fascinating process that has given me insight into the complexity of human nature, and also the characters I write.

Actors have an expression: “Don’t play the end”. Night after night, despite having done it dozens of times before, they must go on stage and convince the audience that they have no idea what will happen or what their character will do. Actors understand intuitively that to be true to life, they cannot play the end because outside the theater no one is playing the end. How could we? While we may like to think we know what will happen in our lives, of course we don’t. Moreover, we don’t know how we will behave when confronted with unexpected and difficult circumstances that force us to make hard choices. What will we do? Who are we really? These are questions that fascinate me. Theater best illuminates these questions when actors maintain the illusion and don’t play the end.

There is a kind of spontaneity in theater that isn’t available to the novelist. Actors forget lines and entrances. They pull pranks, sometimes crack under pressure or majestically rise to an occasion. But characters in books don’t morph on the page and when the reader holds a finished book in hand, the last page will be already written. The entire weight is carried by the novelist. It is the novelist who must make the illusion seem real and convince the reader that characters are making choices in the moment by creating an experience so vivid that the existence of that last printed page is forgotten until read. Only then will readers feel like witnesses to events happening before their eyes.

I confess, I have taken more than a few cues from actors. Like an actor, I put myself in my characters’ shoes. I fear and hope and desire right along with them, fall in love with the people they fall in love with, and I feel the burden of their struggles, ambitions, failures. I walk where they’re walking, go along with what they’re planning to do. And then, I watch them.

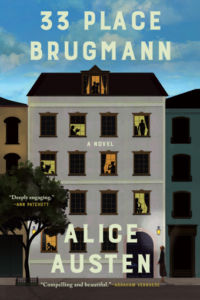

In my book 33 Place Brugmann, I wanted to make that illusion real and bring life to a work of historical fiction that stays scrupulously true to the larger story of the past. This presented a whole new set of challenges, foremost that readers will come to the book knowing the devastating outcome of that larger story—in this case, World War II. The trick for me was to create original fictional characters with uncertain outcomes that readers would not know in advance. Would these characters beat the odds, betray, save, survive? And once again, following the advice I received so many years ago, as I wrote, I watched my characters. They nearly always surprised me. I don’t think any of them were playing the end, far from it, they didn’t know the end. And neither did I, often finding myself modifying the plot I intended to write to accommodate who my characters were and what they did.

I’ve come to believe that every story is a detective story. We all have layers; we are all actors playing our parts. And yes, life is unpredictable, forcing us to make the hardest choices under difficult, sometimes impossible, circumstances that we did not, could not, foresee. To me, those choices are at the heart of fiction, which is an investigation into the mystery of who we really are with the understanding that none of us is playing the end.

_______________________________________

33 Place Brugmann by Alice Austen is available via Grove Atlantic.

Alice Austen

Alice Austen won the John Cassavetes Award for her debut film Give Me Liberty (writer/producer). She is a past resident of the Royal Court Theatre and her internationally produced plays include Animal Farm (Steppenwolf Theatre), Water, Cherry Orchard Massacre, and Girls in the Boat (Dramatic Publishing). She studied creative writing under Seamus Heaney at Harvard, where she received her JD, after which she moved to Brussels and lived on Place Brugmann. Austen currently lives in Milwaukee and is working on a new film and her next novel.