Place is Not a Character—It is Its Own Story

Morgan Thomas on the Way We Write Natural Landscapes

Early this summer, my partner and I attempted to find an alpine lake. For guidance, we had their cell phone with trail maps downloaded and my Garmin GPS navigator. On our maps, a small oval of blue rested not far from the backcountry site where we had pitched our tent, and a dashed line marked “primitive trail” led directly from our campsite to that blue oval.

This dashed line corresponded to a narrow, overgrown path, which brought us to a soggy meadow. There, the trail on our map continued across a small blue line. The trail beneath our feet disappeared. We wandered toward the creek to our left, my GPS rewarding us by counting down the number of feet we had until we were on the trail. If I stood on the bank of the creek, I was directly on the trail. I’d found it. It wasn’t there. The trail on my map crossed the creek, so we crossed the creek, shimmying along a fallen log into dense, young forest. We followed the map’s line up a ridge and paused at the edge of a small cliff. The line on my map continued off the edge. We gave up.

The next morning, headed back to our car, we passed a man and a woman hiking out. They were headed to the lake, the man said.

We said, Couldn’t find it.

Oh, it’s easy, he said. You just follow the run-off. It drains from the lake, leads you right to it.

This is place—sentient, determining, the ecology with which other beings in our stories co-create their lives.

When I think about place in fiction, I think about this moment. Following the run-off to the lake is approaching place as dynamic. An alpine lake drains in a trickle to a creek. Follow the water uphill, and you find its source. Following a dashed line on a screen to a blue oval on that same screen and believing you’ll arrive at water is approaching place as static, a series of unchanging coordinates, imagining that place imitates map.

This latter approach to place remained central in my stories until recently. I wrote about Florida from Oregon, using Google street view to detail my memories of that landscape, believing if I included the right building materials, the right highway numbers and bird species, the right proportion of ants and sweat and humidity, I could evoke the panhandle. Place was two-dimensional, a backdrop.

Over the last few years, my approach has shifted. I attribute this shift in large part to my reading of queer ecological texts. I read Matthew Gandy’s description of the removal of shrubbery in London parks, creating promenades for heterosexual couples at the expense of urban wildlife habitat and gay cruising spaces. I read Pinar Sinopoulos-Lloyd’s definition of gender as an aspect not only of person, but of place, the “confluence of place, culture/race/ethnicity, animistic relations/hauntings, and sovereignty.” I considered how my behaviors and identities were influenced and circumscribed by place.

As my understanding of place changed, so did my writing about it. Place in my stories became increasingly responsive. Place began to incite plot and to inform structure. In one recent story, methane in drinking water affects a queer surrogate’s ability to carry her fetus to term. In another, a photo booth acts as a time machine, facilitating a meeting between two genderqueer people who lived a century apart. In a third, a series of lists mimics the accumulation of debris left by receding floodwaters. In workshop letters responding to these stories, readers said, “this is place as character.”

I understood this phrase a compliment. I’ve heard it used to describe the work of Jesmyn Ward and Samanta Schweblin, among many others. Workshops on writing place as character have been offered by AWP, Hugo House, Grub Street, and Catapult. One class description reads, “bring setting to life so it becomes a character as much as any… human characters.”

But place is already alive. Embedded within this phrase are assumptions worthy of interrogation. Matthew Salesses, in Craft in the Real World, notes that the phrase is most often used to describe settings underrepresented in the white settler fiction tradition, suggesting that the phrase exoticizes the texts it’s used to describe. I am interested in an adjacent but distinct assumption—the assumption that any aspect of a story which is alive, which has desires and motivations, which affects plot, is a character. Character in fiction craft usually designates humans or anthropomorphized beings. Suggesting that to enliven setting is to humanize it perpetuates anthropocentric ideas that only humans are capable of dynamic and complex responses to stimuli.

Yet a field of weedy mustard, faced with drought, begins flowering earlier, a shift encoded within ten years at the level of DNA. The quino checkerspot butterfly, which entomologists believed would go extinct unless humans saved the species through relocation, has in the last decade shifted to higher altitudes and a new host plant, confounding human predictions. The Mississippi River bed just south of the Old River Control Station has risen thirty feet in the last twenty years, sediment accumulation which, unless the Army Corps steps in, will soon result in a channel migration, the river abandoning New Orleans for Morgan City. The cultivated fields, rivers, and urban greenspaces in which we live are both alive and dynamic. Rendering these aspects of place successfully on the page requires recognizing place not as backdrop or character, but as ecosystem—a system of interactions between living organisms and their environment, which leaves physical traces.

When Jesmyn Ward, whose writing has often been described using the phrase “place as character,” writes about her hometown and current residence, DeLisle, Mississippi, in an essay for Time, she describes a strip of forest that white residents have demanded their Black neighbors maintain to separate Black and white neighborhoods. This greenspace is a physical manifestation of centuries of white imperialism and supremacy, which began with white men in DeLisle made millionaires “by cotton, by slavery.” These trees are racism and segregation inscribed in landscape. This is place. Ward also describes people in DeLisle “fighting for a healthier future for the South,” neighbors working side-by-side to dredge beaches, build seawalls, fortify their community against “a surging, endless expanse of time and violence.” These fortifications are community inscribed in landscape. This is also place.

Place in the 21st century is increasingly dynamic.

In addition to landscape, Ward traces the accretion of racism within her body. She describes migraines, diabetes, and the premature birth of both of her children. These effects of place on the body are central to the work of another author whose places have been described to me as characters—Samanta Schweblin. Schweblin’s novel Distancia de rescate (translated as Fever Dream) is told through the perspective of a woman who’s been poisoned by agrochemicals. Place in this novel is agent—contact with a contaminated place poisons the narrator, determining the novel’s structure and inciting the plot—but place isn’t treated as a character. The agrochemicals that poison our narrator are not the result of a vengeful and capricious place-being who, having been poisoned, visits retribution indiscriminately on every resident and visitor to the town. Rather, the poisonous chemicals in this rural Argentinian town are a physical manifestation of a global food trade that prioritizes mass production above sustainability and safety. This is place. Schweblin says in an interview that her novel “could be set anywhere.” By engaging with place as ecosystem, not as character, Schweblin centers the pervasiveness and banality of this ecological horror.

Both Schweblin and Ward reference climate change in their work. Ward references the rain, the wind, the inexorable waves—images that evoke both the relentless barrage of systemic racism and the hurricanes that sweep up from the Gulf, stronger and more frequent each year. In Schweblin’s novel a poisoned boy is half-saved by “migration” in a “green house.” The novel’s original title evokes the characters’ unsuccessful attempts to rescue their families and themselves from the lethal effects of agrochemicals, evoking our global danger, suggesting we may be too late to rescue our species.

Place in the 21st century is increasingly dynamic. Last year’s “unprecedented” Oregon fire season has been outpaced this year. New York City has seen fifty percent more rainfall during severe storms. Hurricane Ida strengthened from a tropical storm to a category four hurricane faster than hurricanes usually do. Now especially the ability of fiction to accurately render place depends on our understanding of it as a responsive ecosystem. A reflexive insistence that any place in a story that thinks and responds is a character perpetuates narratives of our environment as inanimate, unthinking, unchanging. These narratives have undergirded centuries of environmental degradation and have led to our current climate crisis.

Place is not a character. It’s that eddy up a branch of the Mississippi that swallowed my great-granddaddy’s pirogue. It’s the water in a livestock trough so polluted with methane you can light it with a match. It’s the twenty-two carcinogens commonly found in tap water. It’s the mosquito swell that left three hundred cattle lying dead after Hurricane Laura. It’s the sloughing spider bite behind my knee and the mold in the gap between kitchen tiles. It’s the footprints preserved in White Sands National Park—a human carrying a toddler, their path intersecting with that of a mammoth and a giant sloth. It’s the lava that flowed inexorably toward Heimaey, and it’s the water they pumped from ships to douse that flow. It’s the bear eating salmon eggs from an Alaskan river and the bear knocked out of a backyard tree in Princeton by a fire hose and the bear in the living room of a house in New Jersey, eating peppermint patties while the other resident of that house called 911. That bear was shot, but the bear lives on. Place is mycelia decanting themself through the crevice of a rotting log and the sting of nettle and the tree grown over the frame of an abandoned car, holding the car’s shape long after the frame’s rusted away. Patient as the papillomavirus inert on the floor of a locker room. Sudden and immovable as the deadlocked traffic that requires delivering a baby in the back of a minivan. Swift as the Peshtigo Fire driven on by a hot, dry wind. This is place—sentient, determining, the ecology with which other beings in our stories co-create their lives.

__________________________________

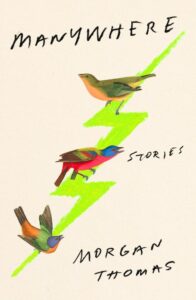

Manywhere by Morgan Thomas is available via MCD x FSG.

Morgan Thomas

Morgan Thomas’s work has appeared in The Atlantic, the Kenyon Review, American Short Fiction, The Yale Review, Electric Literature, and StoryQuarterly, where their story won the 2019 Fiction Prize. They are the recipient of a Bread Loaf Work-Study Grant, a Fullbright grant, the Penny Wilkes Scholarship in Writing and the Environment, and the inaugural Southern Studies Fellowship in Arts and Letters. They have also received fellowships from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and the Arctic Circle. A graduate of the University of Oregon MFA program, they live in Portland.