Pinning Down the Cagey Emotions of Poet Amy Clampitt

Willard Spiegelman on the Mysteries of Biography in the Poetic Realm

In its issue of August 14, 1978, The New Yorker published a poem by a writer previously unknown to its readers:

The Sun Underfoot Among the Sundews

An ingenuity too astonishing

to be quite fortuitous is

this bog full of sundews, sphagnum

lined and shaped like a teacup.

A step

down and you’re into it; a

wilderness swallows you up:

ankle-, then knee-, then midriff

to-shoulder-deep in wetfooted

understory, an overhead

spruce-tamarack horizon hinting

you’ll never get out of here.

But the sun

among the sundews, down there,

is so bright, an underfoot

webwork of carnivorous rubies,

a star-swarm thick as the gnats

they’re set to catch, delectable

double-faced cockleburs, each

hair-tip with a sticky mirror

afire with sunlight, a million

of them and again a million,

each mirror a trap set to

unhand unbelieving,

that either

a First Cause said once, “Let there

be sundews,” and there were, or they’ve

made their way here unaided

other than by that backhand, round

about refusal to assume responsibility

known as Natural Selection.

But the sun

underfoot is so dazzling

down there among the sundews,

there is so much light

in the cup that, looking,

you start to fall upward.

The author was 58 years old and had lived in virtual obscurity for 37 years since she moved to Manhattan from her native Iowa, fresh out of college, in 1941. A manuscript of the finished poem among the author’s papers is dated “5 January 1978.”

Beneath that date, in pencil, she has noted, “Accepted by The New Yorker, 3/78.” Though not a youthful overnight success, she was now on a fast track with regard to publication. The New Yorker began to accept additional work.

Almost four years later (January 11, 1982), another poem—there would be a total of 48 in her lifetime, and two posthumously—appeared in the same magazine. The author used its title for that of her debut book, The Kingfisher, published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1983:

The Kingfisher

In a year the nightingales were said to be so loud

they drowned out slumber, and peafowl strolled screaming

beside the ruined nunnery, through the long evening

of a dazzled pub crawl, the halcyon color, portholed

by those eye-spots’ stunning tapestry, unsettled

the pastoral nightfall with amazements opening.

Months later, intermission in a pub on Fifty-fifth Street

found one of them still breathless, the other quizzical,

acting the philistine, puncturing Stravinsky—“Tell

me, what was that racket in the orchestra about?”—

hauling down the Firebird, harum-scarum, like a kite,

a burnished, breathing wreck that didn’t hurt at all.

Among the Bronx Zoo’s exiled jungle fowl, they heard

through headphones of a separating panic, the bellbird

reiterate its single chong, a scream nobody answered.

When he mourned, “The poetry is gone,” she quailed,

seeing how his hands shook, sobered into feeling old.

By midnight, yet another fifth would have been killed.

A Sunday morning, the November of their cataclysm

(Dylan Thomas brought in in extremis to St. Vincent’s,

that same week, a symptomatic datum) found them

wandering a downtown churchyard. Among its headstones,

while from unruined choirs the noise of Christendom

poured over Wall Street, a benison in vestments,

a late thrush paused, in transit from some grizzled

spruce bog to the humid equatorial fireside: berry

eyed, bark-brown above, with dark hints of trauma

in the stigmata of its underparts—or so, too bruised

just then to have invented anything so fancy,

later, re-embroidering a retrospect, she had supposed.

In gray England, years of muted recrimination (then

dead silence) later, she could not have said how many

spoiled takeoffs, how many entanglements gone sodden,

how many gaudy evenings made frantic by just one

insomniac nightingale, how many liaisons gone down

screaming in a stroll beside the ruined nunnery;

a kingfisher’s burnished plunge, the color

of felicity afire, came glancing like an arrow

through landscapes of untended memory: ardor

illuminating with its terrifying currency

now no mere glimpse, no porthole vista

but, down on down, the uninhabitable sorrow.

Poetry readers—I remember, because I was one of them—scratched their heads and asked, “Where did this come from? Who is this person?” No poems like these had appeared on the scene in quite some time, if ever. Curiosity was piqued. People wanted to find out more about the new author, and to see more of her work.

In “The Sun Underfoot Among the Sundews,” readers heard a measured music that begins with the repeated, almost rhyming vowels of the title; they saw a rendering of a Maine landscape featuring one “of several insectivorous plants of the genus Drosera, growing in wet ground and having leaves covered with sticky hairs” (the author helpfully supplied a note about this ordinary, enticing item when the poem appeared in hardcover); and they were presented with a modest, almost offhand philosophical inquiry into the nature of creation, as well as Darwin’s theory of natural selection. The diction suggests that the poet wanted to update Robert Frost’s ingeniously cheery and vertiginously menacing sonnet, “Design.”

Scholars, critics, and amateur poetry lovers would have noticed that the second poem is full of literary echoes, and allusions to Greek mythology, Shakespeare, Keats, Hardy, and Gerard Manley Hopkins; that it pays homage to more recent and important high culture figures (Igor Stravinsky, Dylan Thomas, perhaps T. S. Eliot); that its diction is mouth-filling, its imagery rich, and its luscious sentences long and complex. It manages at least one cheeky pun—“a benison investments”—about Trinity Church Wall Street. It is obsessed with birds not only as symbols or cultural artifacts but also as parts of our real, physical world.

The poem displays something that all art strives for: a unique style. And it is certainly not an easy poem. It does not even seem personal. It sounds distant and mannered. In fact, it is deeply personal, recounting a love affair gone wrong. It is a confessional poem masquerading as an objective third-person narrative, an extended series of vignettes, with birds rather than people as the central characters.

Its author said of it, “The design here might be thought of as an illuminated manuscript in which all the handwork happens to be verbal, or (perhaps more precisely) as a novel trying to work itself into a piece of cloisonné.” This is not entirely helpful to a reader of the poem, but the characterization derives in part from the author’s unsuccessful efforts for about twenty-five years to write fiction, and then her distillation of narrative into lyric.

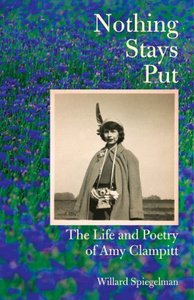

Amy Clampitt was a retiring presence, a background figure, however flamboyant she was on the page.

The poem is by, and about the life of, Amy Clampitt. Its origins lay in something from her life that had occurred more than a quarter century earlier. It is autobiographical, perhaps at second hand, but not revelatory. A biographer might understandably wish to associate it with the verifiable experience of its author, if he could ever connect it to matters in her life. But he would be foiled.

Amy Clampitt was a retiring presence, a background figure, however flamboyant she was on the page and then, at the height of her celebrity later on, however visible. As Doris Myers, one of her oldest friends, said in an interview, “She wanted to tell the world things, but she didn’t want completely to share herself.” Poems that appeared in earlier, more personal forms became, as they were revised for publication in her five elegant volumes from Knopf, more impersonal. Revelation and concealment were partners in her psychological makeup.

In his inaugural lecture as the Oxford Professor of Poetry, W. H. Auden remarked that when he read a poem that moved him he asked himself two questions. The first: “Here is a verbal contraption. How does it work?” And the second: “What kind of a guy inhabits this poem?” By the latter he did not mean the sum of minute biographical facts about the author, but rather the kind of mind and temperament that we might infer, by reasoning back from effect to cause.

That said, we are always grateful, even eager, for additional information about the maker, the real person who “inhabits” the poem or novel or painting we admire. An artist’s life is necessary, but never sufficient, to explain her art.

*

How does one measure an artist and her achievement? Can one define a person by her literary work? These are questions for critics and scholars. And a related question: Who deserves a biography?

In an ideal world, everyone would get one, the written equivalent of Andy Warhol’s 15 minutes of fame. All lives can be made interesting. Every life, every biography, can give what Samuel Johnson most valued: something that “comes near to us, what we can turn to use.”

A poet’s life is not intrinsically more compelling than anyone else’s. Everything depends on the methods of the teller. And no biography can be complete, however, because all lives, even ones well observed and documented, are partial. All are replete with contradictions and unsolvable mysteries. No one is the same person to everyone in her sphere. People see one another through a unique lens or, often, through more than one lens. Some visions look clearer and cleaner than others, which may be muddy or opaque.

But perceptions, memories, and attachments often overlap. We assemble a life from the shards of evidence and recollection that remain. A life in many pieces can be made to look whole.

We learn from people’s reports about her that she often remembered the names of cats but not of their owners.

Clampitt, who lived from 1920 to 1994, presents special challenges to a would-be biographer, and her life still warrants attention in the 21st century. Her visible presence on the American poetry scene lasted for less than two decades, and it will be for literary scholars and historians, as well as the general public, to determine her place in the pantheon. She bloomed late and then died too young, but her poems continue to generate both heat and light, and she still has fans, numerous and enthusiastic.

Her poems evince a life engaged with books, and in political protest and religious struggle. They are not confessional outpourings. They open up to us a woman deeply connected to the physical world, who wrote about nature, landscape, and weather in the most detailed ways.

They mingle Keatsian lushness and Quaker austerity, an unusual combination and one evident in Clampitt herself. These poems, her artistic legacy, open a window onto their maker. This is one reason to examine that maker.

We should also have a written account of her life because we can regard her as one of the Patron Saints of Late Bloomers. It took her a long time to come into her own. The Latin proverb poeta nascitur, non fit (a poet is born, not made) is not entirely true in her case.

Clampitt may have been born with a genetic predisposition and capacity to write. From an early age she was sensitive to language, first as a reader, and then as a schoolgirl who played around with words on the page. But she had to make herself a poet, and she did so only after many wrong turns and many years of failure.

And a third reason to pay attention to her life is that our current culture has begun to express appreciation for women who in generations past led exemplary lives, privately as well as publicly: “Overlooked No More,” says The New York Times of its series of obituaries of previously ignored role models. Before she became famous, Clampitt was living eccentrically, but with aspirations to something grander.

She had as many facets as a diamond, as great a depth as a cave of wonders. She sets an example. The last sentence of Middlemarch, the George Eliot novel that Clampitt read over and over because of her identification with its author and with Dorothea Brooke, its heroine, sums up Amy’s status before she found fame, or fame found her:

… the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

For almost 60 years she faithfully led a life that was mostly hidden, and certainly unhistoric. Then followed a coming out into the spotlight.

*

The external shape of Amy’s life before her two decades of renown (roughly 1978 until 1997, when the Collected Poems was published posthumously) is clear in its outline. Born in Iowa to a Quaker family of farmers on June 15, 1920, the eldest of five children, bookish and slightly eccentric from an early age, she was graduated from Grinnell College in 1941 and, following a summer working with European refugees at a Quaker establishment in Iowa, she made a beeline for New York.

In her 1993 Paris Review interview, she said that “the happiest times in my childhood were spent in solitude,” mostly reading, and that she felt like a social misfit. The absence of mountains or oceans in her native Iowa made her hanker for an entirely different landscape. She left the landlocked Midwest, although she never entirely shook the Iowa soil from her boots.

She had a fellowship for graduate school at Columbia in English, but dropped out, perhaps before the year was up, and soon went to work at Oxford University Press as a secretary, and then rose to the post of promotions director for college textbooks.

In 1949 she won an essay contest sponsored by OUP, for which first prize was a trip to England. I’d like to believe that she beat out dozens of other applicants for the prize, but we don’t know anything about the competition. The anodyne assignment for the essay was something like “Why I Wish to Visit England.” Traveling to a country that she knew of only through literature changed her life: “I believed that the past could be experienced as the present.” The prize made her wish come true.

Postwar Europe possessed a magical appeal for Americans hungry for high culture, for poets as well as everyone else who was unable to get there during the 1930s, owing to the Depression, and Amy with the head of Oxford University Press, when she arrived by ship in England, 1949 the 1940s, owing to the war.

Things began to open up in the late 40s, even though much of Britain and the Continent was still a destroyed war zone. Recovery came slowly. England retained vestiges of war rationing until 1954, but educated Americans were now eager and able to see the real thing with their own eyes, and to visit sites they’d experienced only in books, pictures, and university classes, as well as movies and newsreels.

The poets all went: Robert Lowell, James Merrill, John Ashbery, Adrienne Rich, James Wright, and others like Anthony Hecht, Howard Nemerov, and Richard Wilbur who had served in the Army but were hardly at that point in tourist mode. (Hecht, who was born into a family with some money and considerable cultural aspirations, had visited Europe with his parents as a child in the 1930s.) With the help of Fulbright grants, awards from the American Academy in Rome, and especially the generally favorable exchange rate, they took advantage of peacetime conditions. And Amy happily joined them.

After her return, she went back to work but then left the press permanently in 1951, to write a novel, which turned into several novels, and to travel through Europe more extensively for another five months. When no publisher accepted her novel, she got herself another job, this time as a reference librarian for the National Audubon Society. Birds, like cats, weather, and landscape, remained perennially fascinating to Clampitt, the woman and the writer: “She was galvanized by nature,” remembered her oldest New York friend, Phoebe Hoss.

Indeed, in her mature poetry nature often becomes—as it did in her life—a surrogate for the direct treatment of personal relations. (We can say the same thing about Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, another American poet equally alert to meteorology but reticent with regard to internal weather, and who often allowed the first to represent the second.)

Thus, “The Kingfisher” and many other poems, in which outward data provide an outlet for guarded emotions. She was always reserved. We learn from people’s reports about her that she often remembered the names of cats but not of their owners.

Is it coincidental that she took up poetry writing for the first time since adolescence when she began to feel the attraction of the Episcopal Church in the mid-1950s? Or that her major poetry coincides with her later abandonment of the church in the late 1960s and early 1970s in favor of political activism? Looking back, she allowed, “What I see in Christianity now is a kind of template of human nature—by which I guess I mean mainly human suffering.”

Her poems began appearing in magazines, and she rose like a comet on the literary scene in the late 70s.

She left the church but rechanneled the religious impulse. In a letter to a friend who became the abbess of a religious order in England, she described “the dangerous qualities of faith, the destructive potentiality of faith, as well as its creative, constructive features.” In 1977, having written poems for more than a decade, she took a creative writing class at The New School. It confirmed her sense of vocation, and it released energies that were previously pent up.

In the 1960s and ’70s, she came into her own in several ways. She started working as a freelance editor, then went to Dutton Books, where she was known as the “Book Doctor,” and began writing poetry with greater earnestness. She became involved in antiwar and other political pursuits.

The other encouragement for writing poetry came in 1968. She met the man who became her life partner, Harold Korn, a law professor at New York University and later Columbia, through their shared political activity and work with the Village Independent Democrats. They were campaigning for Eugene McCarthy in his idealistic, perhaps quixotic drive to become president. She moved in with Hal in 1973, keeping this cohabitation something of a secret from her more conventional relatives, at least at the start, but she also held on to the small walk-up apartment in a Greenwich Village brownstone that remained the Woolfian “room of her own” until she was forced to give it up in the last year of her life when the building was converted into co-ops.

She married Hal several months before her death. This long-deferred marriage is one of many parts of her life that are mysterious. According to some friends, she had always opposed marriage on principle. Other friends said that Hal would not marry a non-Jew while his observant Orthodox mother was still alive. The reality is always thornier, more complex than the facts.

Her poems began appearing in magazines, and she rose like a comet on the literary scene in the late 70s, praised by many and derided by some. A MacArthur Fellowship in 1992 gave her the first real money she ever had. “I know how to live poor,” she told Doris Myers. Finally, she did not have to be poor. With her prize money she purchased a modest gray-shingled Cape Cod cottage outside Lenox, Massachusetts, almost adjacent to Tanglewood and close to Edith Wharton’s The Mount.

In the spring of 1993 she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She died in Lenox 18 months later.

__________________________________

From Nothing Stays Put: The Life and Poetry of Amy Clampitt. Reprinted by arrangement with Knopf. Copyright © 2023 by Willard Spiegelman.

Willard Spiegelman

Willard Spiegelman was for many years the Hughes Professor of English at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, and the longtime editor of the Southwest Review. A recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Guggenheim, Rockefeller, and Bogliasco Foundations, Willard is the author of eight books of literary criticism and personal essays, including Nothing Stays Put: The Life and Poetry of Amy Clampitt, and is the editor of Love, Amy: The Selected Letters of Amy Clampitt.