I sat in a small room full of rolling metal file cabinets that rose from floor to ceiling. This room was quiet, there was no window, and I was alone. No one else came in or out. The door must have been dense, likely fireproof, because I couldn’t hear anyone walking down the hall. I was suspended in silence, in the midst of these thousands of documents—contracts and maps and titles—lost in another time amidst the swirl of calligraphied letters made of black bleeding pen, in search of the names Eliza, Minerva, or Juba. Everyone had told me that the chances I’d find anything about the women were slim to none. I went to Charleston to search for them, anyway.

I wound the handle on the side of one of the stacks, rolling the shelf so I could walk down the narrow corridor of space I’d created, scanning thick leather-bound books for the embossed letter C. There. I hauled down one of the massive books. It felt like something from which a wizard might study spells. I hauled it over to the small reading table on the far wall and set it down with a thick thump. I flipped through oversized pages of contracts, all written in those calligraphied marks that I wasn’t yet good at deciphering.

I’d stare at the words until I could see a name, a location, the details of a contract. I’d just spent three hours looking for the contemporary address of the land Susan and Hasell—and therefore Eliza, Minerva, and Juba—had lived on in Charleston. I got to the early 1900s, and then the trail stopped. 6 Cumberland Street today is not the same as 6 Cumberland Street in 1837 or even in 1910. I sat in that silent room for the last few hours of the workday, wondering if they might forget I was there and lock me in; I took pictures of everything connected to the family, and finally, just before sunset, with dozens of photos saved on a small hard drive, I emerged into the fresh air. It blew over me like a welcome back to the world.

I walked down to the French Quarter, meandered past restaurants that were full of tourists, and headed for the harbor. The smell of the sea had always mended me; each day, I’d sit by the harbor or on a beach and let my body soak in the negative ions. When I stared out at the water, though, all I could see was the graveyard, as Slave Mart Museum docent Christine Mitchell had explained it to me the day before. In the 19th century, Charlestonians could smell the “slavers” long before they entered the harbor, because of the stench they bore. As I dug deeper and deeper into the archives, I learned more and more about the particular horrors of enslavement, and the terror whiteness had wreaked over time, a history of which my body is inevitably a part.

This all started with a quilt top that wooed me in. I’d been quilting for years by the time I went to the textile and costume collection at URI, where I was earning my PhD. I swooned over the rows of old dresses and shoes, all carefully tagged and boxed and labeled with a picture on the front of the treasures within, teasers of what’s to come should you select that box. Everything there had once held a body; some still bore the marks of knuckles (on the gloves) and knees (on the pants) and elbows (on the jackets), a spill down the front that would never come out. We know how big Susan’s waist was—26 inches—because we have the dress she stitched for herself. We put it on a mannequin, and she’s embodied again in this puffy-sleeved gown with a matching shawl to keep her shoulders warm.

The same fabric from the dress is included in the quilt I studied. I fell in love with this quilt. The allure of its touch, of the tender paper templates in the back with beautiful calligraphic 19th and 18th century writing on browning documents, alongside orange mimeographed school notices. It was a puzzle, a mystery, something to decode and sit with and uncover. When I touched it, I was touching the stitches women 200 years ago had made, the closest I could ever get to touching their hands.

I looked at the stitches and I could see their fingers, moving just as mine did, only more skillfully, up and down and up and down and up and down, swiftly seaming the hexagons into rows and flowers and stars. And who had held the pens that made the letters on the papers? Who had typed the words for the mimeographed copies? Made the numbers and added the figures in the snippets of accounting?

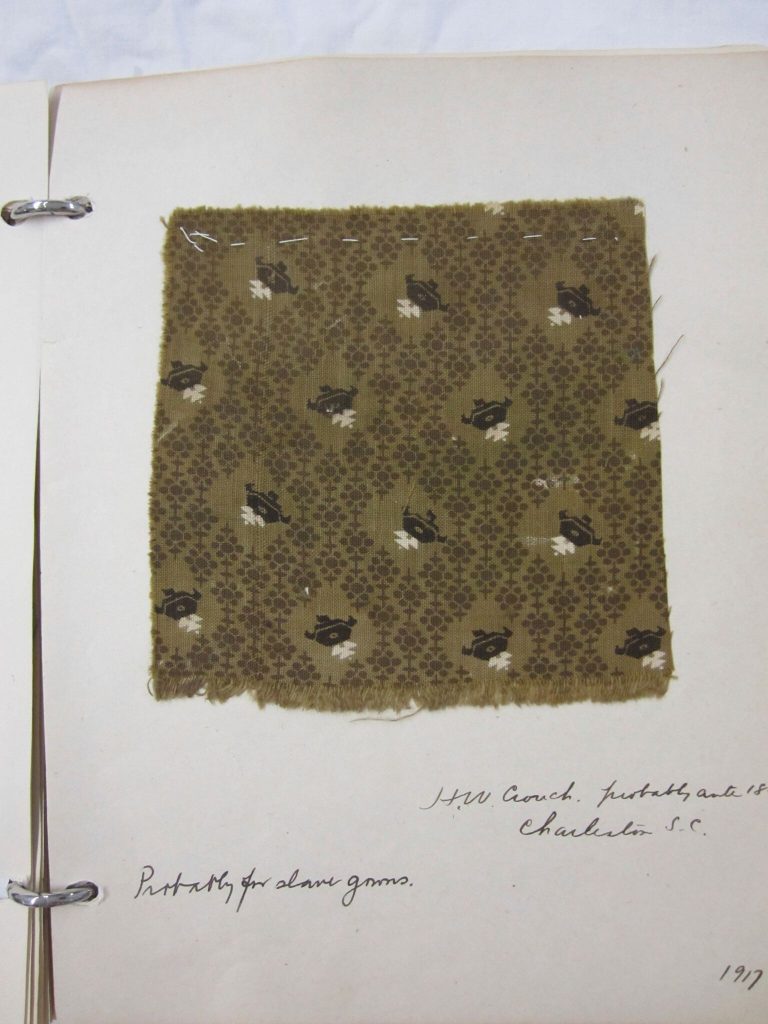

Probably for slave gowns.

When I read those words in a notebook accompanying the quilt tops, I realized there were enslaved women in this story, their lives and bodies embedded in this quilt, like the lives and bodies of the white couple who had owned them. But, we no longer had their dresses, as we had Susan’s, because the enslaved women would have had to wear theirs until they were threadbare. They would not have had the privilege of stitching several day dresses, as Susan did, nor even of selecting their own fabrics. They might have had two dresses at a time, unless they were able to make secret gowns by sourcing their own fabric with barters and trades from the market, sewing into the late hours of the night.

As far as I know, we’ll never be able to see them embodied in the now as we can see Susan standing in front of us again when we don the dress on a mannequin. For the enslaved women, we have the scraps of fabric in the notebook and in the quilts, in two colorways (red and brown); we have to imagine what the dresses might have looked like.

Who were the women who wore the gowns? I’d found their names in the letters Susan and her family wrote. Eliza, Minerva, Juba. Where had they come from? Could I find their descendants, as I was confident I could find the white slave-owners’? The enslaved women were asides in an archive meticulously devoted to a white, middle-class, slave-holding family. It would take me many months of reading in critical race theory, African-American history, material culture theory, and archive theory to learn the lessons of the archive and the history of the United States, from African-American historians and archivists.

I zigged and zagged as quickly as I could on that first journey to Charleston, running (literally) across the city, from one repository to the next, sweating in the lowcountry humidity. I searched in the College of Charleston’s Special Collections, finding a file on Charles Crouch, Hasell’s uncle. I raced over to the public library to look in their South Carolina Room and found the genealogical history of Hasell’s father, Abraham, and his wife, as well as a census record for Abraham’s household in 1820, which recorded 12 enslaved people.

While Abraham’s family members were dutifully recorded by name, gender, and age, the enslaved people he owned were noted only with slash marks on the page under gender and race. I ran to the Historic District to walk the neighborhood where Abraham and the 12 enslaved people had lived, taking photos of his house, which still stands today down near the battery on palmetto-lined streets. It was a wealthy man’s house then as it is now, three stories high with multiple balconies and a great wall around the yard. Draft horses carrying tourists clopped down the road, bringing with them the stench of manure and horse-sweat, while tour guides, holding the reins, talked about what a grand neighborhood this was in the antebellum years. No one was talking about enslavement.

I kept searching for Juba and Eliza and Minerva, and, I learned that a woman named Jane was owned by Hasell and Susan, too. I went back to Charleston, and to Columbia, SC, to find documents in the state archives; I met with living historians in South Carolina and Massachusetts; interviewed historians; toured museums and historic homes and plantations in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Washington DC, Virginia, South Carolina, Wisconsin, and Cuba; observed a plantation excavation (in Cuba) and a slave cabin restoration (in Virginia); slept on a cabin floor in Wisconsin where an enslaved man named Toby (and likely many more enslaved people) had lived; and read and transcribed hundreds of letters from Susan and Hasell and their family members, from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries.

I read Susan’s diary of hand-sewing and knitting, a weather journal another family member had kept for decades, meticulously noting cloud cover and rain and snow and sunshine and wind, some of Hasell’s notes on homeopathic cures from his years in medical school, notes of his ancestor’s from a class at Brown University, store ledgers, hundreds of receipts, and contracts. So many contracts.

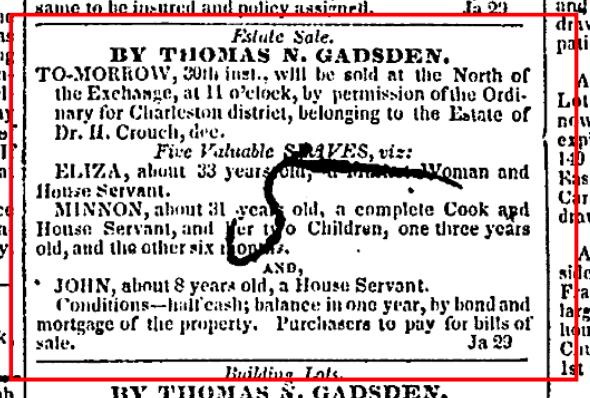

Of course, because enslaved people were seen only as property, it was the contracts and the letters that held the most information. With the help of a genealogist, I learned more from newspaper advertisements alerting potential buyers to the sale of Minerva, Eliza, Jane, and Juba, as well as Adam and George, who were owned by Susan’s other brother and forced to labor at his lumber mill; when the mill went under, Adam and George were sold with it.

Jane was a talented seamstress who could make anything a person in 1830s Charleston could have required. She probably mended her own dresses many times over and could even have been in charge of sewing the “gowns” for herself and Eliza, Minerva, and Juba. It was Juba who cooked for the family and the other enslaved people; she had at least one son, Sorenzo or Lorenzo. We know she had more children because Susan wrote that her own son had learned to call Juba “mammy” from hearing Juba’s children do so.

What were her childrens’ names? How many little ones did she have, and what happened to them when she was sold in 1837? Remarkably, the genealogist found a death record for Juba Simons in Charleston after the Civil War. Juba survived enslavement and the brutal Reconstruction years that followed. I wept when I saw that record, marking her birthday to the day—which most enslaved people did not know as it was denied them by their slaveowners—and her age at the time of death.

By the time I learned about Juba’s death record, I was well into writing the book, years into this research. I had notebooks and notecards and folders full of research, stacks of books tabbed with post-it’s, dozens of files of transcribed letters. How would I possibly make this into a coherent narrative? While it could have been easier to fictionalize this story, I believed it was important to keep Minerva, Eliza, Jane, and Juba Simons’ stories grounded in nonfiction. Their lives had already been nearly erased from this record; I had no idea what they’d endured and overcome during their lifetimes.

Fictionalizing felt like—if not another violence then at least another form of disrespect. I wanted the facts as we knew them to be printed in a public record, so that—maybe—someday, someone who knew them as their own ancestors might come along and find these facts and know a little bit more. And, it felt like a small insertion into—a revision of—the archive to have gathered and recorded what we could of their lives.

Leaving the archives behind and sitting alone in a room with a single light, coffee ever-brewing, I made sewing my model, the rhythms of hand-stitching—the way the needle drops down and then up and down and then up—and piecing, the arrangement of parts—where does the sky blue belong? The hot pink bird print? The mustard yellow apple print I love. Here, and here, arranging the parts.

I collaged together secondary historic sources, personal essay, primary sources, to tell the story of Susan and Hasell and Eliza, Minerva, Juba Simons, Jane, and the other people Susan and her relatives owned. To bind together disparate sections of the story, I wove in my own personal stories and experiences traveling to learn more about the history of cotton, 19th century enslavement in the US, textile mills, and the false distinctions between northern and southern involvement in enslavement.

Over a year later, I still carry this archive around with me everywhere I go, reassessing everything I learned and seeing it again through the lens of this great swath of material. I analyze interactions and exchanges with Susan, Hasell, Eliza, Minerva, Jane, and Juba in mind. I’m looking as much for what’s unsaid as what’s said, for the gaps and silences and absences, for the asides where stories lie, for the connections that reveal systems of power and the ways that I’m implicated—we’re all implicated—in the injustices swirling around us and the triumphs of those, like Juba Simons, who overcome them.

__________________________________

An American Quilt: Unfolding a Story of Family and Slavery is out now from Pegasus Books.