David T. Hanson is a photographer, mixed-media installation artist, writer and teacher. He studied and worked as an assistant to Minor White and Frederick Sommer, and earned an M.F.A. in Photography from Rhode Island School of Design. Hanson is the recipient of John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship and two National Endowment for the Arts Visual Artists Fellowships; his work is held in the permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Art Institute of Chicago, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, among others. Wilderness to Wasteland is his third book. The following excerpt is from the Afterword by Miles Orvell.

David T. Hanson’s photographs offer a range of imagery and an abundance of visual pleasures—from deadpan records of the vernacular landscape to sublime yet troubling aerial vistas; behind all of his work, however, is a tough edge of irony and intelligence that compels us to look again at what’s there before our eyes. As a landscape photographer, Hanson stands in a long tradition going back to the 1860s, and he has inherited the various practices of photographers who have pictured the earth in ways that have been widely diverse and even contradictory, from Carleton Watkins to Robert Adams. He has inherited as well the vision of the great landscape painters, from Thomas Cole in the 1830s to Charles Sheeler in the 1930s. Inheritance is not imitation, however, and Hanson’s work is unique among contemporary photographers in synthesizing a historic vision with a revelation of the future that is informed by a strong and factual sense of environmental change. The result is a body of work that compels our attention on three levels—aesthetic, historic, and moral. If Hanson is, for our time, a moral witness to the ravages of unchecked industrial development, he is also a photographer of astonishing beauty, and he poses the challenge to the contemporary viewer of how to reconcile these two responses.

Next to Florida State Highway 84, Everglades, Collier County, Florida

Next to Florida State Highway 84, Everglades, Collier County, Florida

Looking east toward Middle Butte, Atomic City, Idaho

Looking east toward Middle Butte, Atomic City, Idaho

Mt. Con Mine waste pile and remains of Corktown, Butte, Montana

Mt. Con Mine waste pile and remains of Corktown, Butte, Montana

In titling this volume Wilderness to Wasteland, Hanson posits a short history of the American landscape—a history that begins in wildness and ends in despoliation. As the title suggests, Hanson’s chief interest for many years has been the environment, and Hanson was one of the earliest ecological landscape photographers to use color. Although we think of environmental art as a product of the late-20th century, its roots go back to the 19th century and can be seen most notably in the work of painter Thomas Cole, who establishes the essential background for an understanding of much contemporary landscape art.

Born in England, Cole settled in the United States in the 1830s, where he responded immediately to the majesty of the Hudson River Valley, seeing it as a place of splendid seasonal beauty, wild cataracts, open vistas, abundant trees, and space for the farmer’s cultivation. Moreover, it was a place that embodied a benign future for American democracy, promising “peace, security, happiness.”[i] But Cole soon observed a changing landscape in the Hudson Valley, reflecting a radically changing social economy that was allowing the unchecked entrepreneurial spirit to exploit natural assets like lumber that one might have assumed were to be held as a sustaining common resource.[ii] (Around the same time, Ralph Waldo Emerson, in “Hamatreya” and “Nature,” would note acerbically some of these same changes around Concord, Massachusetts; Emerson pretended amazement that the farmers there could think they “owned” the land with full title, land that was there to serve the poet’s eye and spirit.)

Mt. Con Mine and Centerville, Butte, Montana

Mt. Con Mine and Centerville, Butte, Montana

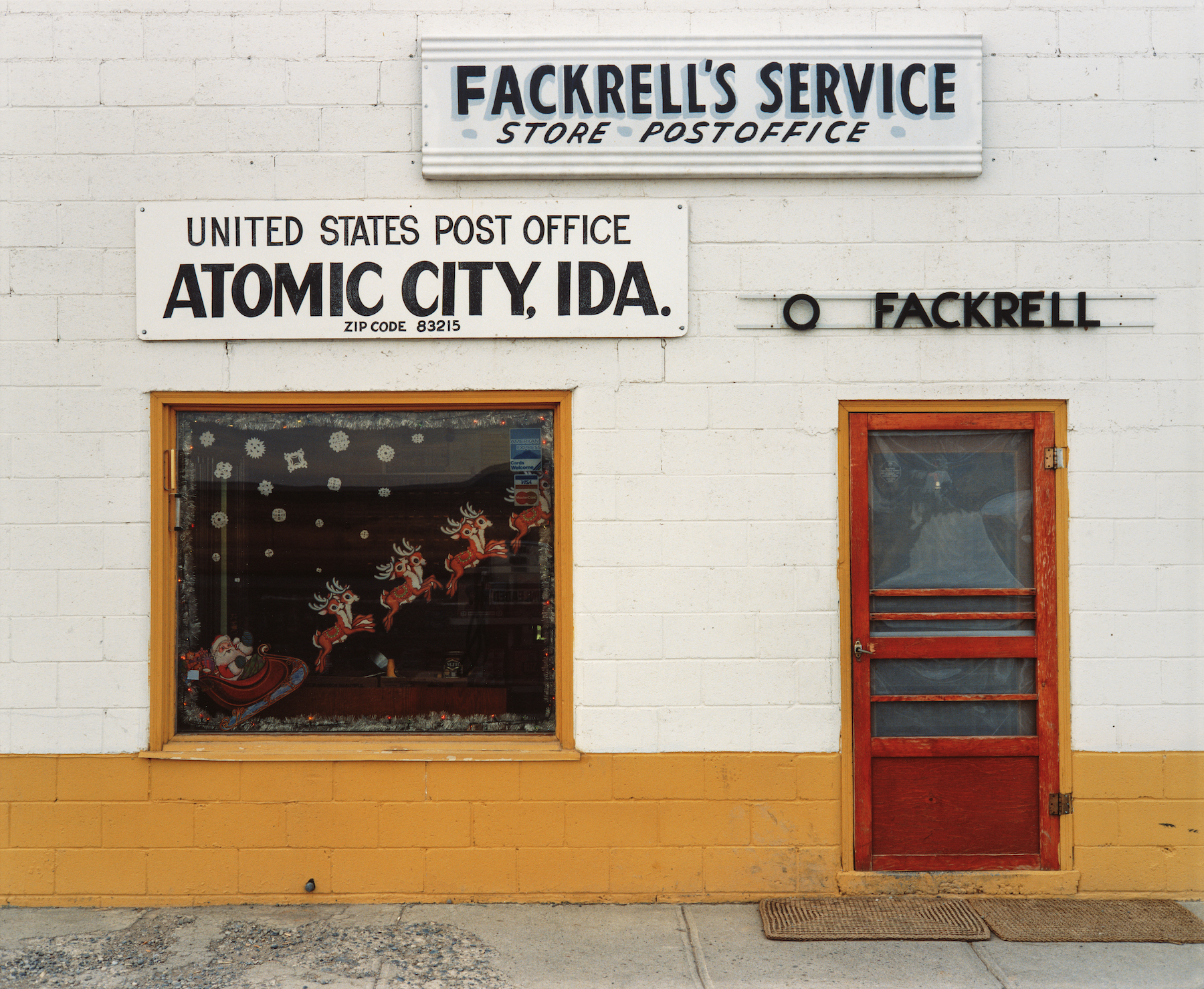

Fackrell’s Texaco Store & Bar, Atomic City, Idaho

Fackrell’s Texaco Store & Bar, Atomic City, Idaho

Kirkland Cemetery, Childress County, Texas

Kirkland Cemetery, Childress County, Texas

Main Street, Butte, Montana

Main Street, Butte, Montana

In his 1836 “Essay on American Scenery,” Cole lamented the quick passing of the beautiful landscapes he had treasured—and painted: “the ravages of the axe are daily increasing—the most noble scenes are made desolate, and oftentimes with a wantonness and barbarism scarcely credible in a civilized nation. The wayside is becoming shadeless, and another generation will behold spots, now rife with beauty, desecrated by what is called improvement; which, as yet, generally destroys Nature’s beauty without substituting that of Art.”[iii]

Cole was observing the creation of landscapes of destruction, though he chose not to paint them; instead, he framed his scenes carefully so as to preserve an idealized view of the Hudson River Valley. But he was haunted by visions of ruins in other forms, and he brought them into several of his paintings in the late 1830s, including The Course of Empire series, which depicted a history of civilization that would lead from The Savage State of wilderness to the idyllic Pastoral State to The Consummation of Empire to the Destruction of pomp and power to a final condition of Desolation in which the once-mighty architecture of imperial power is reduced to ruin, overtaken by nature.

Butte, Anaconda and Pacific Railway yard along Silver Bow Creek, Butte, Montana

Butte, Anaconda and Pacific Railway yard along Silver Bow Creek, Butte, Montana

Waste slag and irrigated cropland along the Jordan River, Sharon Steel Corp. Superfund site, Midvale, Utah

Waste slag and irrigated cropland along the Jordan River, Sharon Steel Corp. Superfund site, Midvale, Utah

Slag and mine waste along Silver Bow Creek, Butte, Montana

Slag and mine waste along Silver Bow Creek, Butte, Montana

Tooele Army Depot Superfund site, Tooele, Utah

Tooele Army Depot Superfund site, Tooele, Utah

The United States did not have any such ruins—as Europe of course did—but Cole’s allegory was picturing a possible future that might befall the growing nation, as the forces of exploitation turned the beauty of wilderness into “wealth,” the product of a political economy that favored the dollar over everything else.

Missing in Cole’s vision for America was what we have come to call a “middle landscape,” one in which there might be a balance between forces of development and the preservation of a sustainable environment. The idealized depiction of such a moment found expression most famously in George Inness’s The Lackawanna Valley (1855), whose integration of technology into nature—a locomotive chugs along happily into the middle ground of a bucolic landscape—became an icon of American culture, discussed most notably by Leo Marx in The Machine in the Garden. But by and large the middle landscape is a dream that could not be realized in a nation whose values were overwhelmingly on the side of “free enterprise,” which assumed that it was the American’s “Manifest Destiny” to remove the Native American and get on with the important business of appropriating and exploiting the Indian’s former lands.

That process—the systematic exploitation of natural resources—was in fact depicted by photographers in the 19th century, though in ways that seem at odds with the middle landscape idyll that Inness had painted, and this too forms an important context for understanding Hanson’s effort.

–Miles Orvell

Yankee Doodle tailings pond, Montana Resources’ open-pit copper mine, Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area Superfund site, Butte, Montana, 1986

Yankee Doodle tailings pond, Montana Resources’ open-pit copper mine, Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area Superfund site, Butte, Montana, 1986

Twilight in the Wilderness Standard Oil Company of California, El Segundo, California

Twilight in the Wilderness Standard Oil Company of California, El Segundo, California

Sunset on the California Coast Union Oil Company of California, Richmond, California

Sunset on the California Coast Union Oil Company of California, Richmond, California

[i] Cole, quoted in notes for The Oxbow, by Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, in John K. Howat, American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), p. 127.

[ii] See Angela Miller, who quotes the Englishman Basil Hall’s observing, with dismay, the slashing and burning practices of the nascent lumber industry around this time. Angela Miller, “The Fate of Wilderness in American Landscape Art: The Dilemma of ‘Nature’s Nation,’” in Alan C. Braddock and Christoph Irmscher, eds., A Keener Perception: Ecocritical Studies in American Art History (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009), p. 94.

[iii] Cole, Thomas, “Essay on American Scenery,” American Monthly Magazine 1, (January 1836), p. 12.

Interstate 15 near Barstow, California

Interstate 15 near Barstow, California

–

Wilderness to Wastland is published by Tavern Press

Foreword by Joyce Carol Oates

Afterword by Miles Orvell

Introduction by David T. Hanson

Taverner Press, 2016

All photographs © David T.Hanson.

Lit Hub Photography

Photography excerpts are curated by Catherine Talese and Rachel Cobb.