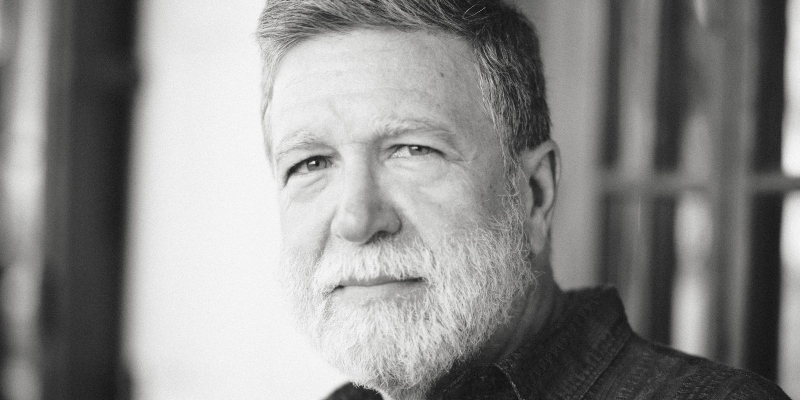

Peter Turchi on Writerly Digression and Charming Sentences

In Conversation with Mitzi Rapkin on the First Draft Podcast

First Draft: A Dialogue of Writing is a weekly show featuring in-depth interviews with fiction, nonfiction, essay writers, and poets, highlighting the voices of writers as they discuss their work, their craft, and the literary arts. Hosted by Mitzi Rapkin, First Draft celebrates creative writing and the individuals who are dedicated to bringing their carefully chosen words to print as well as the impact writers have on the world we live in.

In this episode, Mitzi talks to Peter Turchi about his new book, (Don’t) Stop Me if You’ve Heard This Before and Other Essays on Writing Fiction.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

From the episode:

Mitzi Rapkin: You have a chapter on digressions and misdirection and asides. And I think that question of what is right and wrong in fiction, at least when you have first lessons in fiction, and people say, for instance, never have backstory, then you have heart palpitations every time you start to write backstory, even if it’s 20 years since you got that advice, and you’re talking about digressions in a way they can make people feel good, like it’s okay to have a digression. And sort of this question that you’re holding is everything essential to the story? And how do you measure that?

Peter Turchi: Yeah, well, that’s a good question. You know, there’s the old-fashioned notion that the ideal novel or story would be all perfect words, you know, each word perfectly chosen. But there are a variety of people, Robert Cohen, who once gave a talk on great sentences, and as part of it said, not every sentence in a story should be great, you need room for the great ones to shine, so, you need some quieter sentences, too.

Kevin McIlvoy, who recently passed away gave a wonderful lecture on useless beauty. That is the moments and stories and novels which aren’t plot oriented, and may not even change our understanding of character, but in their own way add something to the work. So, I think the notion that everything needs to be pared down to what’s absolutely essential, is one of those rules or pieces of advice that is exaggerated to ill effect.

I think one of the reasons we read is for the pleasure of the prose, and so a well turn sentence may, in fact charm us, even if it does a modest job in the overall telling of the story and maybe it doesn’t have anything to do with plot at all. But yes, how much of that? I don’t think there’s any easy formula for that. It depends, I suppose on how much we’re charmed. We will tolerate quite a lot of digression, as I tried to argue in the book, when it’s entertaining, and when it seems managed by someone.

So, in that classical story, The Story of the Old Ram by Mark Twain, which is a story about comic digression, that was one of his most popular pieces. When he was on the lecture circuit, people would actually call for it, and he knew he had to tell it, even though everybody had heard it. Everybody had read it, too, but they wanted to hear it. He deliberated over it, speaking of strategic release of information, to the timing of his pauses.

Twain was a very slow and deliberate speaker. He would calibrate the pauses in the telling of that story because he said all of the humor depended on how much space he gave it. But that’s the story entirely about digressions but if we’re trying to get directions somewhere say, or we’re calling 911, we don’t have much tolerance for digression. We want to get right to the heart of things as quickly as possible. So, it’s all a matter of the context for that work.

***

Peter Turchi is the author of seven books and the co-editor of three anthologies. His books include (Don’t) Stop Me if You’ve Heard This Before; A Muse and A Maze: Writing as Puzzle, Mystery, and Magic; Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer; Suburban Journals: The Sketchbooks, Drawings, and Prints of Charles Ritchie, in collaboration with the artist; a novel, The Girls Next Door; a collection of stories, Magician; and The Pirate Prince, co-written with Cape Cod treasure hunter Barry Clifford, about Clifford’s discovery of the pirate ship Whydah. He has also co-edited, with Andrea Barrett, A Kite in the Wind: Fiction Writers on Their Craft, The Story Behind the Story: 26 Stories by Contemporary Writers and How They Work and, with Charles Baxter, Bringing the Devil to His Knees: The Craft of Fiction and the Writing Life. He currently teaches at the University of Houston, and in Warren Wilson’s MFA Program for Writers.

First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing is a literary podcast produced and hosted by Mitzi Rapkin. Each episode features an in-depth interview with a fiction, non-fiction, essay, or poetry writer. The show is equal parts investigation into the craft of writing and conversation about the topics of an author’s work.