Peter Orner and Emma Cline Discuss Endings, Memory, and Writing Against Classification

“A last line isn’t the last line, it’s just the last one we say out loud.”

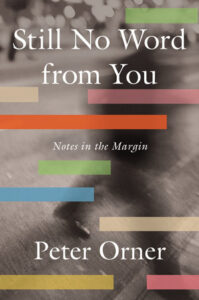

Peter Orner’s new book, Still No Word From You, reads like a full expression of a mind, in a different way than a novel might be an expression of a mind. There isn’t the artifice or costume of fiction, in these 107 short pieces, but there isn’t the blunt assumed authority of nonfiction, either. The tone is intimate, digressive, and personal, and the cumulative effect is a total immersion in the author’s way of seeing.

So much of the pleasure in this book comes from Orner’s impressions of what he’s read. There’s a piece about Kafka and people who are “exceptional readers,” and, finishing this book, I had the same thought about Peter Orner: it’s almost like a parallel life, or an ongoing dream, the way his reading occupies him, but only an exceptional writer can make that interior work legible to others. Clean, strong prose, a tendency to indulge a riff, humor and melancholy woven together—you’d follow wherever the writing leads.

–Emma Cline

*

Emma Cline: I loved how this book captures, formally and tonally, the strange way memory works and lives inside us—without logic or linearity. I see it in the way that you return to the same incidents, or indulge digressions, and in certain preoccupations of place or gesture, how flashes of the past can double in on the present, like how a memory passes over us and dissipates, though obviously there’s narrative control at work, too.

You’re circling, in ways both direct and oblique, how our lives are shaped and distorted by memory and time, and though you’re not talking about your own work, in this quote, you might as well be: “…The only honest way of trying to construct an actual life on the page. A gathering of fragments. Of the stories that get told about us. Of the stories we told. Unordered, like our thoughts in any given day we lived.”

Peter Orner: I think circling is a great way to put it. Like those vultures around a fresh piece of meat down below, you know what I mean? I do have this feeling sometimes that certain memories recur because we’re still circling above them. Maybe we’d rather view them from up there, until we’re ready to go down and deal with them. And you never really know, or at least I don’t, when that’s going to happen. I’m carrying this metaphor too far, but I think this gets to what you say about memory often not having a logic or linearity. I think we can impose this.

Maybe we spend a good part of our lives trying to impose a kind of order of our memories. We tell ourselves, this is what’s happened in my life. There was this, and then there was this. And then I fell in love. And then I fell out of love. And then I got hit by car. And then my favorite uncle died. But we don’t, or at least, I don’t remember things in any particular order, and that was what I was trying to get at, or at least I think it was, in hindsight, what I was trying to get at. See? In hindsight we attempt to establish order. Order that never really was there. I’m tied up in knots here. But what else is new?

With Still No Word I wanted to try and track the connection between memory and reading. How but for having read someone else’s words, we wouldn’t have called to mind a certain story.

EC: The book is organized into six parts: Morning, Mid-Morning, Noon, Afternoon, Evening, Night. There’s an elegance to using the straightforward, ordinary span of a day as a structure to hold all these disparate stories and lives and digressions. It felt a bit like an echo of the larger project of your work—how you focus your attention on these seemingly familiar, daily moments, holding them up to the light and turning them round so they suddenly expand and illuminate.

I’m curious where that structure came from—was it after the work had been collected, a way to organize the pieces? Or did you write towards the structure? And what resonance did it have for you?

PO: I think you hit it, and thank you. I love that, holding up disparate stories up to the light. As I was writing this I thought a lot about what we think of as an ordinary day. Another Monday, another Tuesday—but if you take just a couple of minutes to think about, is there, seriously, such a thing as an ordinary one? Take today. Nothing different or strange has happened, at least not yet. I walked the dog. I came into White River, to my studio in the old hotel here. I drank coffee, I read a little.

I’ve been reading Lydia Davis’s translation of Madame Bovary. Pretty good book, right, whoever translates it. But damn, Davis. Take this line from Chapter 2, “She was on the doorsill; she went to get her parasol, she opened it.” How could this day be ordinary if I read a line like that this morning? How weirdly charged that first passive part of the sentence, followed by those two so-called ordinary actions. But whose observing it? That hapless goofball of a doctor, Charles Bovary, and he doesn’t even know how charged these lines are. How did I get on this tangent? The day. What makes up a day? And is it possible that one could be ordinary?

One of the essays is about Bernadette Mayer, and she’s kind of the patron saint of the day, having written a masterpiece called Mid-Winter Day on a single day in, I think, in December of 1978. You can’t believe how much she does, doesn’t do, remembers, conjures, imagines. You wrote with one hand, cooked dinner for her kids with another. Organizing around the concept of a single day was kind of homage to Mayer who proves beyond any doubt the point I was fumbling about, that is that an entire day is a universe.

EC: You write that you practice a form of nostalgia bordering on the hysterical—what are you talking about?

PO: A friend once told me that once, that this is what I do. And it’s probably true. Is this true for you? That certain memories, even bad ones, take on a kind of sepia hue after a while. I’m not saying we want to go back and experience them again, only that for better—not for better, for worse—they make up whoever the hell we’ve become. There was this bully in seventh grade. I write about him. He used to beat the shit out of us for fun. Do I want Jordy Crenshaw pummel me again? Not really.

But I look back and yeah, I’m nostalgic for those days. When he’d stand in a tunnel near school and wait for us. And because I circle around this memory so much, I experience it more than I ever did in life. How many times did Jordy beat me up? Maybe twice? But in memory you circle, you return. Now he’s kicked the shit out of me a hundred times, and somehow it brings a little joy to think about it. This is where it becomes hysterical, possibly.

EC: Could you talk a bit about your writing process? Am I remembering that you maybe write a draft of a piece all the way through, and then rewrite the whole thing from the beginning again? What does that approach do for you—is it a momentum thing, are you after a kind of cohesion in the writing experience?

PO: God, I wish I knew exactly. Yes, I do have to write things over and over from the top, sometimes, copying the exact same piece the exact same way, with maybe a shift of a comma or something. Momentum, absolutely. Without it, don’t you think a paragraph is doomed? Cohesion, too. And also a connection to the piece. If I can’t try and wrap my brain around it, I seem to lose my hold on it. This is probably why I tend to write so short. One of the reasons anyway. The other is my hand starts to hurt. I often have to soak it in a little bowl of warm water, which allows me to pretend I’m a concert piano player. And I’m a guy who basically flunked piano lessons.

This thing we hardly understand, death. And the rest of the things we call endings, the endings of sentences, books, movies, love, marriage, friendship, the end of a hallway, the end of a street, the borders of countries, the shoreline—aren’t endings at all.

EC: I know you’ve written novels, and more straightforward “fiction” stories—how did you land here, in this tone and form and length? On the back of the book, it says “Essays/Literary Criticism”—which doesn’t seem to fit exactly. Does the distinction even matter, while you are writing? Or at all?

PO: It never matters when I’m working. It probably should sometimes, as it does matter in terms of publicity and marketing. If people can’t place your book, it’s hard to sell it. I’ve always thought this was a uniquely American problem. This need to shelve a book in the right slot. I think some other literary traditions have less of a hang-up on what to call a piece of work. What the hell is Calvino’s Invisible Cities? It’s just this remarkable, totally genre-defying piece of work. (A plug here for Mairead Small Staid’s terrific The Traces, about, among other things, Invisible Cities)

And is Amos Tutuola wonderfully bonkers The Palm-Wine Drinkard a novel? Really? Isn’t it a form of storytelling that doesn’t quite fit in anywhere other than its own world? With Still No Word I wanted to try and track the connection between memory and reading. How but for having read someone else’s words, we wouldn’t have called to mind a certain story. It’s a universal, normal thing. But I’m not sure we celebrate it enough. People have been calling the book a memoir in essays. I can live with that, but again, where do you squeeze in that this is about other people’s words as much as it is my own?

EC: Do you have an approach to your endings? Is it instinctive, a rhythm or tone you’re after, or is it more worked over than that?

PO: I’ve been thinking about this question for the last hour. Something just came to me, I don’t think it’s any kind of revelation, but isn’t there only one true ending? This thing we hardly understand, death. And the rest of the things we call endings, the endings of sentences, books, movies, love, marriage, friendship, the end of a hallway, the end of a street, the borders of countries, the shoreline—aren’t endings at all.

I say this because we can always re-read a sentence, re-live love through memory. When we reach the end of a street, we can turn around and walk back where we came from. We can re-read a book we’ve finished. I guess what I’m trying to say is that I wonder if an end of a piece is actually the end, and if we aim for that we fuck it up. You know what I mean? So a last line isn’t the last line, it’s just the last one we say out loud.

_____________________________________

Still No Word from You: Notes in the Margin by Peter Orner is available now via Catapult.

Emma Cline

Emma Cline is the New York Times bestselling author of The Girls and the story collection Daddy. The Girls was a finalist for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, the National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Award, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. It was a New York Times Editors’ Choice and was the winner of the Shirley Jackson Award. Cline’s stories have been published in The New Yorker, Granta, The Paris Review and The Best American Short Stories anthologies. She received an O’Henry Award and the Plimpton Prize from The Paris Review, and was chosen as one of Granta‘s Best Young American Novelists.