Perspective, Art, and Humanism: Understanding Resilience with Sarah Hall

The Author of Burntcoat Talks to Jane Ciabattari

Norwich-based Sarah Hall was born and raised in the Lake District. “I wasn’t raised by wolves, but I did grow up raking around outside, overnighting on the moors, swimming in fell pools and interacting with, probably, more animals than humans,” she explained in The Guardian in 2018.

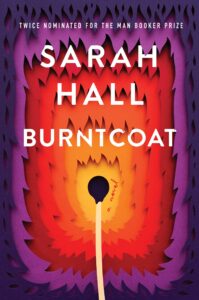

Hall is the author of five novels: Haweswater (2002), set in Cumbria in 1936 when a village is to be flooded to create a reservoir for Manchester (winner of the Commonwealth Prize for best first novel); the Booker-shortlisted The Electric Michelangelo (2004), which features a Coney Island tattoo artist; the dark dystopian feminist The Carhullan Army (2007), the Man Booker-longlisted How to Paint a Dead Man (2009), a collage of four narratives set in the art world, and The Wolf Border (2015), an exploration of the reintroduction of the Grey Wolf to the Lake District. She also has written three award-winning story collections (she has won an O.Henry award and the American Academy of Arts and Letters E. M. Forster Award, and is the only writer to win the BBC National Short Story award twice, the only author to have been shortlisted four times). The COVID pandemic inspired Burntcoat, her uncanny fever dream of a new novel, with Eros and Thanatos at its core. And it transformed her life.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have you managed during this past 18-plus months of turmoil and uncertainty?

Sarah Hall: It’s been hard and traumatic. Sadly, I was one of the statistics in terms of a relationship breakdown during lockdown. Also, I was not able to be with my father who lived at the other end of the country—he was sick and isolating—and he recently died after contracting Covid. I was responsible for home schooling my daughter, so my work was compromised (more than it already is as her primary carer). I guess I’m pretty tough in some ways, so I’ve managed to operate and remain level during the worst of it. The best thing that has risen through is appreciation for the amazing friendships I have—these relationships have been vital and fortifying and I have come to realize that women particularly tend not to let other women down in hard times.

JC: When did you begin writing Burntcoat? When the lockdown began? What specifics inspired you to write it?

SH: I started the novel the first day of our first lockdown—in March 2020. There was a lot of fear and uncertainty about the disease itself and the implications for society, wild speculation too, and questions about how we would survive and what we would be like on the other side. I responded to all that. The close relationship I have with my daughter, our little protectorate, was part of the inspiration. And of course, older fomenting interests and preoccupations came into the novel—I have a degree in art history, and I’ve mused over catastrophes, amplifications of current events, and future what-if scenarios, throughout my writing career.

JC: What personal experiences did you bring to the novel? What was based on research, and what was your research process? Did you consult other books about the plagues, the pandemics that have burnt through human communities in the past? Which ones?

SH: I have first hand experience of Turkish culture, working artists, a Lake District childhood, and a binary mother/daughter relationship. Iranian and Japanese friends supported other cultural and geographical research. I got to grips with pandemics, epidemiology, and invented my own virus with the help of a brilliant virologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (a fairly terrifying experience!). I also spoke with a large-scale art installer who has been responsible for some very controversial projects in the UK.

I could easily imagine the pieces my protagonist Edith makes but needed to understand the logistics and practicalities of how they could be constructed and erected, the machinery used, the finances involved. In addition, the director of the Baltic Art Centre in Newcastle shared generous insight into the commercial art world and institutional support for developing practices. There are aspects of what was actually happening outside, real-time, within the novel—in terms of civil unrest. But I’ve always been interested in government contingency planning, disaster mapping and management; there’s a whole shelf of (rather alarming) such books on my bookcase.

JC: The opening line to Burntcoat is, “Those who tell stories survive.” It’s advice your narrator, Edith, has as a child from her mother Naomi, a writer, who has been left with brain damage after a blood clot in the brain. And it has many possible meanings, she points out. The child Edith thinks it means “survivors tell stories.” Later, Edith wonders, “Is it possible to be saved, like Scheherazade seducing the enemy with tales? Do stories make sense of a disordered world?” What elements of this theme fascinate you?

“It’s an exploration of our human desire to reconstruct the world and its history and so process it—to tell stories about who we are and make sense of, and meaning from, our existence.”

SH: I suppose it’s an exploration of our human desire to reconstruct the world and its history and so process it—to tell stories about who we are and make sense of, and meaning from, our existence. Edith is puzzled by her biological and psychological longevity. She survives the pandemic and the virus lies dormant in her body for decades before returning. So she wonders how she has cheated death. Through her sculpture she is telling the story of human mortality and human connection. Perspective, art, memory, humanism; they combine for Edith as she tries to understand her personal resilience, and her life. It’s true that survivalism, storytelling, symbolism, and finding significance in art and literature, fascinate and exhilarate me.

JC: Is there a warehouse like Edith’s studio, Burntcoat? Or other artists’ residences in the North?

SH: Yes! There is a building—an old electricity station in Norwich, Norfolk, where I used to live, that has writing painted by an artist called Rory Macbeth on the exterior walls. The text is Sir Thomas More’s Utopia. It’s a big old utilitarian building next to the river. I’ve transplanted it to the north of England in my book and altered its architecture a little to look more like an Ottoman han. I imagined different writing on it—Naomi’s last novel. My book contains feminist versions of other iconic art works in Britain—like the Angel of the North, which towers over a road in the North-East. Recognizing women’s prowess and ambition is centre stage in much of my work, and depicting women as cultural agents and history-makers is important.

JC: Edith addresses her lover Halit throughout the novel, beginning in the opening pages: “You arrived just as that brilliant ill star was annunciating. I imagine you as a messenger. You were the last one here before I closed the door of Burntcoat, before we all shut our doors.” The lockdown begins, a love story begins. Did you envision the tragic arc of Edith’s tale as you began the novel? How did that evolve?

SH: I believe I did intuit that the love story would be tragic from the beginning. But is it tragic? It is curtailed. All our lives and relationships are curtailed, or at least they end. “Every death is an early death,” as Halit quotes to Edith. And yet their strong connection—bodily and emotional—remains after death. What I was trying to do with their love story was accelerate a relationship—within the compression of lockdown—through lifelong iterations. Sex, intimacy, trust, companionship, loyalty, practicality, even the imaginary parental… these create a union, a partnership, that moves through stages of care, emotional and physical, to loss, bereavement, memorialization. It’s a very erotic book, but it’s also a book that focuses on love in a truthful, non-romantic way, and the latter stages of the relationship are perhaps the most powerful, significant and heroic definitions of love. Caring for the dying lover – is this not real, manifest love? I like the premise that love is a behavior, not just an emotion.

JC: Amen to that. Edith is an outlier, a rebel, a radical sculptor whose work is original, primal, whose signature work is “Hecky,” the “Scotch Witch,” a “half-burnt assemblage lofting high as a church tower, containing all the unrealistic belligerence and boldness of early ambition….She rises above the yellow furze as if from a pyre, hair streaming on the updraft, her back arcing.” Edith ends up creating a memorial for victims of the demonic virus. Your passages about her artistic process, including her works in progress, are thrilling. Where did you develop this understanding of her art form? How would you compare it to the creation of a novel?

SH: I wanted to create a successful, competitive, avant-garde, and respected female artist. There haven’t been enough of them in history, or they have not been credited enough. As the most prominent sculptor in the country, Edith is given the commission for creating a national monument commemorating the millions of pandemic victims. That alone felt radical to conceive—her apex status. Her work is unorthodox, dark, disquieting, divisive, earnest, and accomplished. Of course, I really hope to create that kind of “art” too, with my writing. Her final piece—the memorial—takes her decades to complete and it’s uncomfortably assembled and disassembled many times. The process of drafting and editing words might be similar. I loved researching shou sugi ban, the cedar burning technique Edith learns in Japan and uses in her sculptures. Here, the surface of wood is burned and brushed, to make it stronger, waterproof, and perhaps more beautiful. This, along with nova’s viral fever, which, if it doesn’t kill the victim allows the immune system to be “treated,” and the studio name of Burntcoat, form the central metaphor for the book. It’s all about the damage, experience, and resilience equation.

“Sometimes my writing doesn’t feel like a written language to me at all, it feels more like music or painting, its sensuality seems beyond the words.”

JC: You’ve written before about artists—a tattoo artist in The Electric Michelangelo, several generations of painters in How to Paint a Dead Man, others in your short stories. You studied art history as well as literature. Is visual art a trigger for your writing?

SH: Absolutely. In some ways those influences are more important than literary ones. Or at least they are an endless source of inspiration. It’s not just about populating the books with artists or using art pieces as triggers for stories and ideas. Sometimes my writing doesn’t feel like a written language to me at all, it feels more like music or painting, its sensuality seems beyond the words. It’s a strange thing to try to describe—a poetic, a discipline, experiential communication, that isn’t just about fiction. I feel like a maker as well as a writer, and I hope true artists will forgive me for saying that.

JC: When I finished reading the novel, I felt I had come to the beginning. Then I turned back to the beginning, and indeed it was circular in structure. What are the advantages and disadvantages of that approach?

SH:The book is a memory piece. I think we—like Edith—make narratives out of memories. Moments, textures, events, feelings, emotions, they combine and then are given shape and significance in the mind. We try to make meaning and sense of everything and the human brain loves patterns. This is, I hope, a short, power novel (le puissant petit!) and in some ways that form is not dissimilar to the short story form, in which openings and endings are often co-dependent. In recollecting a life, we do really note its bookends and its trajectory in between.

JC: Will you write more about the pandemic? What are you working on now?

SH: No, probably not, I feel I’ve completed the task. I also have a short story called “One in Four” (in the collection Madame Zero) which is a suicide letter written by a whistle-blower at a very big powerful drug company, and that story deals with a new influenza pandemic and buried research studies. So I have dealt with the material before. I’ve recently written a few nonfiction pieces and spoken on the radio about bereavement and Covid. A piece I was writing, about being pallbearer at my mother’s funeral six years ago, suddenly took on the recent loss of my dad. I’ve been quite outspoken about our government’s poor handling of the pandemic, including the gas-lighting the nation has endured, and corruption deep within the Conservative party that isn’t being held to account. I am working on another novel—I’d been working on it for a long time and Burntcoat arrived in the middle of it and sort of exploded things. That’s not uncommon for my process. And peculiar short story ideas always keep coming, a bit like dreams.

__________________________________

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall is available now.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.