Pedro Almodóvar on Adapting Alice Munro for the Screen

"Munro’s inspiration has meant a real moral, aesthetic, and tonal adventure"

“The complexity of things—the things within things—just seems to be endless. I mean nothing is easy, nothing is simple,” Alice Munro said in an interview.

That sentence defines with precision the life and work of the Canadian writer. Simplicity and at the same time denial of that simplicity. Simplicity in order to talk about what is complex, about what happens in front of our eyes without us being able to appreciate at first glance what is extraordinary, bizarre, terrible, grotesque, and mysterious about it.

In Alice Munro’s stories, nothing is what it seems; beneath her serene writing there is always something compulsive. Munro has a prodigious ability for finding terrible things within simple things. That ability transforms her into a mistress of suspense. When I read one of her stories, I have to re-read it immediately because at the end I have the sensation of knowing less about the story than at the beginning. By means of little hints, comments that arise on the fringes of the main narrative, Munro changes the direction of the story almost without us noticing.

I remember my wonderment and astonishment when I read “Chance,” “Soon” and “Silence,” the three bitter stories from the Runaway collection that share Juliet as the protagonist and that made me think that I could take possession of them and turn them into a film. Everything is unpredictable throughout Juliet’s life, from her introduction on the train (the 1960s for Alice Munro, which I transferred to the 80s; sexual emancipation didn’t arrive in Spanish society until then) to the solitude of her middle age, abandoned by her daughter without a word of explanation.

Munro’s Juliet is a special young woman, cultured and discreet (nothing like the typical thrill seeker), but she has a temperament and a determination capable of taking bizarre, reckless decisions. In the first story—”Chance”—Juliet is a young teacher of classical literature who has just finished a period of substitution at the school where she works, and she doesn’t think twice about going on a long train journey to visit a married man with a sick wife, whom she only knows from having coincided with him one night on a previous train journey (Eric, a lobster fisherman who will become the man of her life and the father of her daughter). I don’t want to reveal the continuous surprises that await the reader of these three stories, only to add that from those first pages the character and the unexpected events that she lives through in the following two stories seemed to me to provide precious material for making a film.

I began the adaptation by writing everything to do with the train. Putting into practice Munro’s idea about the concentration of events in a single place and circumstance (things within things), all the essential elements of the narrative appear in the block of sequences on the night train. On that journey, Juliet comes into contact with the two most important poles of our existence: death and life, and, as a consequence, sexual pleasure, the passion of the senses (as the only way to escape from the idea of death), the conception of a new life, and the birth of guilt.

Despite the cultural and geographic distance, I have always felt very close to Alice Munro’s themes: the family and family relationships in a rural, provincial, or urban setting. And also the desire, the need to escape from all that; always one thing and the opposite, without that meaning the slightest contradiction. Within the family, Munro’s specialty is the female characters. Mothers, daughters, sisters, mistresses, friends, grandmothers, housekeepers, neighbors, etc. Women with a great moral autonomy. Munro is not a complacent writer with her characters, nor is she, I suppose, with her own life, so dear as to provide the title for her latest book (Dear Life), the most autobiographical of all.

When Munro talks of her characters’ need to abandon the routine in which they live, she uses the terms “escape,” “hiding,” and “disguise.” This drive for escape and concealment is very present in Juliet’s three stories. She abandons her sick mother, Sarah, in “Soon,” because that is the natural course of life; a young woman gives priority to the home she has created with a man by whom she already has a daughter, Penelope, rather than to the place where her sick mother is living with a father overflowing with health and desires which he satisfies with another woman who isn’t the mother. It’s very tough (Munro’s stories are always tough) and at the same time something natural but not any less heartrending for that. At the end of “Soon,” for example, we understand Juliet, but we also think that she is mean to her mother, however much we empathize with her. At the end of “Silence,” it is Juliet who is left on her own: her daughter Penelope goes off to a spiritual retreat and doesn’t see her mother again or contact her, except on her birthday, when she sends her a blank card so that she should know that she is still alive but that Juliet is not a part of her life. There is a parallel between these two endings that speaks of the turbulent relationships between mothers and daughters. Also at the end of Dear Life, Alice Munro reflects on this point in the only way possible: “We say of some things that they can’t be forgiven, or that we will never forgive ourselves. But we do—we do it all the time.” This reflection can be applied to all three stories.

I found a treasure of inspiration in every line of these three stories, but Munro’s style (the best of her, what makes her a writers’ writer) is unique and belongs to literature. And even though cinema and literature seem to belong to the same family, they are very different, almost opposing disciplines.

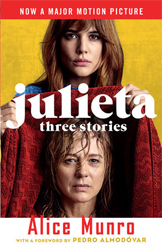

No one should expect Julieta, the film, to be the literal translation of these three stories full of magic and pain—it would have been an impossible task—but that doesn’t mean my film doesn’t depend on them. Julieta exists because previously she was called Juliet, and she lived in “Chance,” “Soon,” and “Silence.” My Julieta is the result of all that links me to Alice Munro (mothers, daughters, fatality, guilt) and of all that separates me—basically our culture and our geography.

Spanish family culture is very different from the North American one. In the United States or Canada, young people become independent when they go to university. In Spain that is inconceivable; we never completely cut the umbilical cord with our parents. From the moment I decided that I would try to adapt the three stories for the cinema, the first thing I did was unify them, transform them into one story—because in Runaway the stories are not consecutive, although they seem to be. Once that was done, I was tempted by the adventure of transforming Juliet into Julieta—that is, transferring Munro’s stories to Spain and setting them within our culture and our geography. After several drafts, it seemed that the idea was working. The story of an adaptation is always the story of a betrayal and a pillage, and the case of Julieta is no exception.

When I say that cinema and literature are diverse disciplines, I don’t mean that they don’t influence each other mutually. While I was writing the script and directing the film, I saw clearly that Alice Munro’s bitter drama demanded from me as a writer and filmmaker a different tone from that which has characterized me until now. I have written many mother characters, but Julieta is very different than all of them. For me, Alice Munro’s inspiration has meant a real moral, aesthetic, and tonal adventure. From the outset, I was fully aware that I had to approach these women in a simple way, that my great adventure would consist of containment and narrative sobriety. Alice Munro’s stories asked that of me.

From the foreword to Julieta: Three Stories that Inspired the Movie. Used with permission of Vintage International. Copyright © 2016 by Alice Munro. Foreword copyright © 2016 by Pedro Almodóvar.

Pedro Almodóvar

Pedro Almodóvar is a Spanish Oscar-winning director and screenwriter known for films like All About My Mother, Talk to Her, Bad Education, Volver, and I'm So Excited.