At every intersection, the patient regrets not carrying dice in his pocket to decide for him whether to keep going in the same direction or turn. Going straight means crossing the next street. Should he ignore the red light or wait for green? Obediently waiting for the light to change would be too square, and ignoring the color of blood too risky. And what if the light just happens to turn green as he approaches? That wouldn’t solve anything either. There’s no such thing as chance, and even if there is, the dice are loaded.

Green is out of the question, so is red. His only hope is the yellow light, a neutral in-between zone. The quince-yellow eye blinks open for two seconds and then shuts again. To seize this opportunity, he’d have to turn into a panther. The patient—not a panther—should forget all about trying to zip down the crosswalk’s zebra back, and instead hang a quick left. Luckily he’s walking on the left side of the street, and not by chance: he always turns left when he leaves the house, no matter whether the building in question is his own or the one where his girlfriend lives. If he turned right at this juncture, he’d soon arrive at a tiny supermarket where one of the cashiers always scowls and the other has compassionate eyes. To which of them will he hand over his money? Walking into a supermarket is Russian roulette.

Since he turns left, a café soon appears. In passing he glances at the coffee drinkers, harvesting their faces like golden grains of wheat. A forehead strikes his eye, a clever forehead belonging to a woman. The patient finds himself ever shorter of breath; the whites of his eyes gleam. Her silver necklace glitters like the Milky Way, and her lips converse without respite. Across from her sits a second woman with a similar hairstyle. Suddenly the woman’s mouth falls silent. How marvelous, that instant when silence enters and the lips part ever so slightly, this time without a voice, as though she were about to kiss him. For the moment, no kissing occurs. First the screenplay has to be written. The patient, who finds traditional words ugly, isn’t able to write. The word kissing, for example, tastes like dill pickle salad. Nocturnal tonguejests would work as an alternate expression. But to use it would be plagiarism.

As the patient zeroes in on the stranger’s lips, his gaze becomes more critical, colder. There’s something wrong with them. Lying there horizontally, the lips resemble two dead pieces of meat, producing a structural error: one lip lies atop the other as if it wished to be labeled upper lip. Every sort of hierarchy makes the patient sad. Really the lips should stand vertically on end and enjoy equal rights. While he’s busy overthinking this, something happens that he fears most of all: the absolutely ideal lips appear before him. They possess neither shape nor color. They are perfect but dead. The patient coughs vigorously into his elbow, half-covering his face. Then he lets his arm drop, gives a shy smile, and cedes his place in line to the next passerby: I’m in no particular need, no really, do go ahead, I’m perfectly fine without a kiss. To be honest, I’m incapable of enduring intense physical contact right now. Please, be my guest, enjoy everything on offer here. I’m sure you’ll be a worthy replacement for me.

The patient is surprised to see it’s not a man but a woman standing behind him ready to step in and take his place. Women are just better at certain things, and there’s nothing objectionable about having a woman fill in for you. To be honest, he doesn’t even think it’s the trouser-role tradition coming into play here—it’s just that he put on trousers by accident this morning. He needs to take them off, and since he can’t go to work without them, he’d just as soon stay in bed. Getting sick is one thing, acquiring a doctor’s note quite another. The doctor clicks words on his screen. Tiredness, listlessness, loss of appetite, inability to concentrate, insomnia: made-up words, every single one! The patient knows that not only these words but all the others, too, are inventions—they didn’t grow naturally in the soil.

In any case, he definitely needs a replacement. His stingy institute is only willing to fund a half-time position, in other words, to pay for half an academic. Half a person can’t stay healthy. The person’s other half—the unemployed half—gets sick too. Both together take up a full two hours in the doctor’s schedule. At the institute, the work requires a replacement with two hands. So in the end it’s a matter of two people, not half a person. Why didn’t the institute just create two positions right from the start?

The patient reaches out to shake his replacement’s hand, but there’s no longer a woman anywhere to be seen, and his hand floats aimlessly in midair. That’s odd. She was just standing there right behind me. Maybe she got cold feet. Who’s going to push open the double-winged doors in my place now?

The patient discovers a beautifully tailored figure off in the distance: a comet-like lady coming from the direction from which he, too, arrived. He feels ashamed. His faded shirt, missing buttons, wallet containing only coins. This lady is the flower of all flowers. The scent of chamomile flies up his nose, piercing his brain. The patient feels the urge to sink to his knees because the lady before him is a prima donna who sings the lead in every production; she’s a diva but still as modest as an ornithologist. Each of her footsteps lands precisely on the beat, but there’s nothing staccato about her way of walking; she moves in elegantly elongated, uninterrupted inhalations. With this gentle, decisive gait, she swiftly passes through the double-winged door.

The patient feels proud. Except for him, no one knows that this opera singer lives in Berlin and not the U.S., as most music fans believe. She even lives in his neighborhood—somewhere off to the right, or else she wouldn’t always be following in his footsteps. He always turns left when he leaves the house, but he hardly ever leaves the house, since he hardly ever gets out of bed, and so he hardly ever has occasion to turn left. He can’t remember the last time he left his pillow. When the doctor asks, he tells him he takes a walk every morning. He says this to please the doctor but, oddly, the lab coat recommends staying indoors, particularly in the case of persons incapable of recognizing an invisible danger. Anything else would be foolhardy. But the patient can spot danger more quickly than an emotionally stable individual.

Despite the medical warning, he goes outside. Every morning or never: he’s not quite sure.

On the left, his heart beats in his chest at an accelerated rate; on the right, day draws to a close with the purchase of a carton of milk at the supermarket. Without milk, the coffee tastes burned to him. With coffee, the milk tastes burned. The milk he buys is only 3.5% maternal. The rest is paternal. It tastes watery, a bit salty. He can’t get anyone to tell him where he can buy thicker milk.

There’s no wall blocking the path in any direction, so a person can go where they want. But when it comes right down to it, there’s really only a single direction: from backstage to front and center. The thick wall behind the stage is really just made of velvet. The curtain is heavy, but anyone can open it. The front of the stage is mercilessly illuminated: that’s where the singer has to stand. Once she’s crossed this threshold, there’s no turning back, and no one— not even this veteran artist— can maintain complete control over her vocal cords, because voices are not the exclusive property of humankind. When a person’s voice abandons them, no one can help, not even the artificial heaven overhead, embroidered with golden stars. The musicians, who are bowing, banging, or blowing, fill up every last bit of space with sound, only to produce an enormous silence a moment later—a silence that she, the prima donna, must break all by herself with her opening note. There’s always a song to sing, but first a silence must be created for the song to be born in.

The voice doesn’t come from her mouth. It begins somewhere else, high up in the air where an invisible angel waves to her. No one in the audience can pinpoint the sound’s location.

The patient stares at the double-winged door through which the singer vanished. The door is the plastic case of the DVD. He observes the women visiting the café. It’s said that half of all human beings are women. But that can’t be right. They are definitely more than half. Otherwise the system would collapse. Everywhere he looks, he sees more women than men. Women displaying their skin to the sun. Gleaming upper arms, napes sprinkled with freckles, and a V-shape between their covered breasts. There are also women who toss their luxuriant heads of hair over their shoulders and bring their faces closer and closer to his. He retreats, taking many tiny steps, so as not to be overwhelmed. His feet can already feel the sidewalk’s edge. If he retreats just one step more, he’ll fall off the curb.

Only members of the bourgeoisie are allowed inside concert halls. The patient wishes he were bourgeois, although secretly he believes the bourgeois are no better than the general populace, just somewhat more arrogant. Even after the singer goes to all that extra trouble to sing in Italian, they thank her by voting for the populists, or, as the patient likes to call them, poplarists. Writing “poplar” is a way of getting around the word “people.” The humble, hard-working diva studies the Russian libretto before she sings—and then her public opts for the autocrat. The patient shuts his eyes, wanting to be alone. He’d rather sit in an empty auditorium. Among other things, empty means filled with the dead. The concert hall officially counts as empty because the dead don’t purchase tickets. They show up in a statistic but otherwise remain invisible, gathering wherever there’s music to be heard. The patient thinks he might have to be dead himself to attend. He likes the idea of being dead, or even better: becoming dead. How does one become dead? It’s not the same as dying. Merrily dead and always in attendance.

At this point he strokes his forehead with three fingers. This calms him. He doesn’t want to think too much, he wants to walk. Walking is a way of thinking without words. He has difficulty clearing the word-foam from his head. His head isn’t a space, it’s a dense mass of unconnected words. Not only his brain but even the little hairs in his eyebrows and eyelashes are made of words. His stomach is full of words he finds he cannot digest. This morning for breakfast he ate the word bread. Yesterday, or the day before, or maybe some other day in the past, he bought a loaf of white bread at the supermarket. He urgently needed milk, so he went around the corner three times, making one left turn after the other. Eventually he arrived at the supermarket, where “bread” rhymes with “dead.”

“Slice” is a lovely word; it sounds like something stitched out of silk. A slice of bread. It sounds like warm flesh, a woman’s torso draped in a silky scarf. Not the whole woman, just a thin slice of her. Even if the milk tastes burned, there’s still a slice of hope in the bread. The patient thinks he’s just eating words. In reality, he digests everything that goes along with them, too. Apparently, he swallowed the bread along with the word “bread” because he was hungry as usual, even though he didn’t have an appetite.

He observes the beautiful singer at the same time every day. It amuses him that she seems not to realize he knows who she is. She thinks no one can recognize her because she’s wearing a classic hat, big sunglasses, and a wide scarf that covers her mouth. She doesn’t know that the patient recognizes people by their fingers, not their faces. In the past, he stood in the last row of the top balcony, and the singer on stage was as tiny as a thimble. He couldn’t make out her individual fingers. Now that the concert halls have closed, the patient always sits in the front row at home. The stage has never been closer. When he goes to bed alone after visiting a digital performance space and sleeps through the night without closing his eyelids, a bright new dawn awaits him. There used to be so many gray-on-gray days. Now the sun brings its cheer and chastisement to all the days, and the city looks two-dimensional. To go on thinking in 3D, the patient must add his own shading to its contours.

Meanwhile all the opera houses are open again. At least that’s what people are saying. But the patient has forgotten how to use any form of transportation. He doesn’t remember how to stand on the platform in such a way that no crazy person can push him onto the tracks. Even the steps leading down to the platform are problematic. Walking down them reminds him of the descent into hell, and going up, of the guillotine.

He should get out of the house. That would be a good first step. As a citizen, he has the right to leave reality behind at any moment. Standing on the sidewalk, he can be certain the singer will come from the right. If he turned right, the encounter would be over in a flash. He turns left, and the celebrity follows at his heels. He’s afraid that she—not being afraid— will go on walking straight ahead, while he, unable to cross the street, has no choice but to turn to the left. To his astonishment, she turns left and enters the café. Its interior must be cool, dark, pleasant. But no one dares to go inside. No one wants to get so much sun. Those who’ve lost their homes are subjected to sunlight all day long. For those who can afford the price of some refreshing shade, sitting in an outdoor café is more or less an alibi. The winter will not come in which humankind will have the leisure to process this bizarre summer and come to terms with it. Spring won’t come because winter isn’t coming.

__________________________________

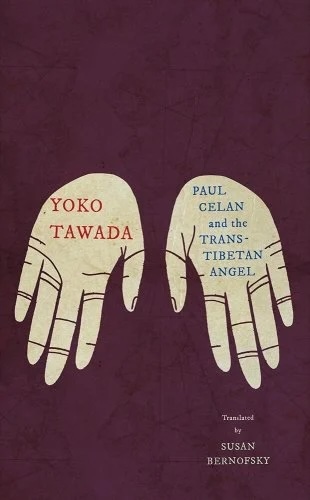

From Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel by Yoko Tawada. Used with permission of the publisher, New Directions. Translation copyright © 2024 by Susan Bernofsky