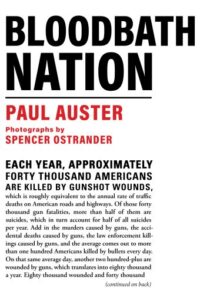

Paul Auster: Why Is America the Most Violent Country in the Western World?

On the Normalization of Gun Culture in the United States

In 1970, I began a six-month stint in the merchant marine, employed as an ordinary seaman on an Esso oil tanker, and it was aboard that ship that I first came into contact with men who had grown up around guns and continued to live on intimate terms with them. For the most part, our cargo consisted of jet fuel, which we hauled up and down the Atlantic coast and into the Gulf of Mexico. Elizabeth, New Jersey, and Baytown, Texas, the sites of two of Esso’s largest refineries, were the end points of all our journeys, with customary stops in Tampa and other ports along the way.

There were just thirty-three men on board, and apart from a couple of Europeans and a handful of Northerners like myself, every officer and member of the crew came from the South, nearly all of them from Louisiana and various towns along the Texas coast. Two of those shipmates jump back into my thoughts now, not because they were especially close friends of mine but because each of them, in his own vastly different way, was instrumental in furthering my education about guns.

Mandalay Bay Hotel. Paradise, Nevada. October 1, 2017. 61 people killed; 897 injured (441 from gunfire, 456 in the ensuing chaos). All photographs by Spencer Ostrander.

Mandalay Bay Hotel. Paradise, Nevada. October 1, 2017. 61 people killed; 897 injured (441 from gunfire, 456 in the ensuing chaos). All photographs by Spencer Ostrander.

Lamar was a short, stringy-haired redhead from Baton Rouge with a bright crimson splotch marring the white of his left eye and eight letters tattooed onto the knuckles of his two hands: L-O-V-E and H-A-T-E, the same marks inscribed onto the fin- gers of Robert Mitchum’s demented preacher in The Night of the Hunter. Lamar worked as an assistant oiler in the engine room and was approximately my age (twenty-three). In spite of the bad-boy tattoos, I found him to be a soft-spoken, agreeable sort, and because we were fellow newcomers on our first ship, he took it for granted that we were allies and seemed to enjoy hanging out with me when we weren’t busy with our jobs. The fact that I was from the North and had graduated from college and had published some poems in magazines were not things he looked upon with suspicion. He took me as I was, I took him as he was, and we got along—not quite friends, exactly, but shipmates on easy, friendly terms.

Then came the first revelation, the first jolt. We had shared enough stories about ourselves by then for me to feel that I wouldn’t be offending him if I asked about the red splotch in his eye. Taking no offense, Lamar calmly explained that it had happened a few years back when he and a crowd of people were standing on a sidewalk throwing bottles at a protest march led by Martin Luther King. A shard of broken glass had flown into his eye and pierced the membrane, causing a wound that had healed over into the ugly red thing that would be with him for the rest of his life. Still and all, it could have been a lot worse, he said, and he felt lucky not to have lost the eye.

First Baptist Church. Sutherland Springs, Texas. November 5, 2017. 26 people killed; 22 injured. The church has been closed for religious services since the day of the shooting. The sanctuary has been turned into a memorial for the victims.

First Baptist Church. Sutherland Springs, Texas. November 5, 2017. 26 people killed; 22 injured. The church has been closed for religious services since the day of the shooting. The sanctuary has been turned into a memorial for the victims.

Until then, Lamar had never said a word against Black people in my presence, and when I asked him why he had done such a stupid, vicious thing, he shrugged and said it had seemed like a fun thing to do at the time. He was in his teens then and hadn’t known any better, implying that he wouldn’t do that sort of thing today. Not that he could have, of course, given that Martin Luther King had been shot down and killed two years earlier, but I chose to interpret his words as an apology, even though I had my doubts. Then came the second revelation.

We were standing on the deck one afternoon watching a flock of gulls circling above the ship when Lamar told me about another one of the fun things he liked to do on Saturday nights in Baton Rouge when he was feeling bored, which was to take his rifle and a pocketful of ammunition, park himself on an overpass of the interstate highway, and shoot at cars. He smiled at the memory of it as I tried to absorb what he was telling me. Shooting at cars, I said at last, you must be pulling my leg. Not at all, he answered, he really did it, and when I asked if he aimed at the drivers or the passengers or the gas tanks or the tires, he vaguely answered that he shot in the general direction of all of them. And what if he hit and killed someone, I asked, what would he do then? Another one of Lamar’s shrugs, followed by a laconic, indifferent, almost blank “Who knows?”

Century 16 movie theater. Aurora, Colorado. July 20, 2012. 12 people killed; 70 injured (58 from gunfire, 4 from tear gas; 8 in the ensuing chaos).

Century 16 movie theater. Aurora, Colorado. July 20, 2012. 12 people killed; 70 injured (58 from gunfire, 4 from tear gas; 8 in the ensuing chaos).

Those two jolts occurred during my first ten or twelve days on the ship, I kept a polite distance between myself and Lamar for several days after that, and then he came to me one afternoon as we were nearing a port and said good-bye. The chief engineer didn’t like his work, he said, and he had been given the boot.

Put a gun in the hands of a maniac, and anything can happen.

Earlier, he had told me that he had gone through a rigorous training course and had passed a written exam to qualify as an oiler, but it turned out that Lamar had cheated on the exam and knew as much about being an oiler as I did. As the chief engineer later put it to me: “That little son-of-a-bitch could have blown up the tanker and every living soul on board, so I kicked his sorry ass out of here.”

So much for my departed comrade, my onetime pal. Not just a bottle-throwing racist, not just a dangerous fraud, but a hollowed-out psychopath who thought nothing about pointing his rifle at anonymous strangers and shooting at them for no other reason than the kick of it, the pleasure of it. Put a gun in the hands of a maniac, and anything can happen. We all know that, but when the maniac appears to be a levelheaded, ordinary fellow with no chip on his shoulder or apparent grudge against the world, what are we to think and how are we supposed to act? To my knowledge, no one has ever provided a satisfactory answer to this question.

West Nickel Mines School (a one-room Amish schoolhouse). Bart Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. October 2, 2006. 6 people killed; 5 injured. All the victims were girls between the ages of 6 and 13. The school was demolished the following week and left as open pasture. Another school was erected in a nearby location six months later.

West Nickel Mines School (a one-room Amish schoolhouse). Bart Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. October 2, 2006. 6 people killed; 5 injured. All the victims were girls between the ages of 6 and 13. The school was demolished the following week and left as open pasture. Another school was erected in a nearby location six months later.

Billy was a different sort of animal—tame, sweet-tempered, and young, just eighteen or nineteen, by far the youngest member of the crew. I was the second youngest, but next to the blond, smooth-faced Billy, I felt positively old. A pleasant kid from a small rural town in Louisiana, he talked mostly about his passion for souped-up cars and hunting deer with his father, whom he referred to as “Daddy” and “my daddy.” We went ashore together a couple of times with the forty-year-old Martinez, a family man from Texas, but apart from liking Billy and promising to go hunting with him one day if and when I happened to find myself in Louisiana, I didn’t know him well. None of that is of any importance now.

Fifty years later, what counts is that on one of our stops in Tampa, we left the ship with Martinez, and as the three of us waited for a taxi to pick us up and drive us into town, Billy made a collect call home from the pay phone on the dock. He talked to his father or mother for what seemed to be an inordinate length of time, and after he hung up, he turned to us with a troubled look on his face and said: “My brother’s been arrested. He shot someone in a bar last night, and now he’s locked up in the county jail.”

There was nothing more than that. No word on why his brother had shot that someone, no word on whether that someone was alive or dead, and if alive whether he was badly wounded or not. Just the bare bones of it: Billy’s brother had shot someone, and now he was in jail.

Umpqua Community College. Roseburg, Oregon. October 1, 2015. 10 people killed; 9 injured. The building where the shootings took place was torn down and a new structure was built on the site.

Umpqua Community College. Roseburg, Oregon. October 1, 2015. 10 people killed; 9 injured. The building where the shootings took place was torn down and a new structure was built on the site.

With nothing more to go on than that, I can only speculate. If Billy’s older brother was anything like Billy himself, that is, a good-natured, reasonably balanced, functioning human being and not some trigger-happy nutjob like Lamar, there is every chance that the shooting of the previous night was caused by an argument, perhaps with an old friend, perhaps with a stranger, and that the disinhibiting effects of alcohol played a decisive part in the story as well. One beer too many, and a verbal dispute suddenly and unexpectedly explodes into a punching match.

Such things happen every night in bars, pubs, and cafés all across the world, but the bloody noses and aching jaws that generally follow from these dustups in Canada, Norway, or France often turn out to be gunshot wounds in the United States. The numbers are both stark and instructive. Americans are twenty-five times more likely to be shot than their counterparts in other wealthy, so-called advanced countries, and with less than half the population of those two dozen other countries combined, eighty-two percent of all gun deaths take place here. The difference is so large, so striking, so disproportionate to what goes on elsewhere, that one must ask why. Why is America so different—and what makes us the most violent country in the Western world?

*

From photographer Spencer Ostrander:

I decided to focus on the physical structures in ordinary American landscapes, the places where we go to work, to pray, to shop, to study, to live out everyday lives. I purposefully didn’t include images of guns, victims, or perpetrators. I wanted to remind the public where these crimes took place, and, what happened to the often forgotten or ignored buildings and landscapes. Places are permanent, you can’t erase a place, you can bulldoze and rebuilt it, you can level it, you can make a monument or leave it as it is. The reality is that it will always exist as the place where these atrocities occurred.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Bloodbath Nation by Paul Auster and Spencer Ostrander. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Paul Auster

Paul Auster is the bestselling author of 4 3 2 1, Winter Journal, Sunset Park, Invisible, The Book of Illusions, and The New York Trilogy, among many other works. He has been awarded the Prince of Asturias Prize for Literature, the Prix Médicis Étranger, the Independent Spirit Award, and the Premio Napoli. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.