Parting Glances: Mourning the Work We Didn’t Get from Queer Director Bill Sherwood

His Debut Was One of the Best Independent Films of the 1980s. He Died Four Years Later.

It’s not clear when Bill Sherwood knew he was closer to the end of his life than the beginning. He was sure he had contracted HIV early on—at least he told some of his friends he was sure—though they didn’t see symptoms, Kaposi’s sarcoma or otherwise. He wrote the screenplay for Parting Glances, his debut feature, in the fall of 1983 and filmed it through 1984, pausing production when he ran out of funds and then starting again when he got more money.

The very last week of shooting was held in March 1985, just when the first HIV tests were approved by the FDA. Sherwood had drafts of other screenplays and he would write several more, but when Parting Glances was released in 1986, he may have at least suspected that this genteel film, a romance set in the early AIDS era, would be his legacy.

Parting Glances is a gem. Steve Buscemi, in his first major screen role, plays Nick, a punk star facing an early death, at times with sardonic reserve, at others with righteous fury. Kathy Kinney—best known as the outrageous Mimi on The Drew Carey Show—portrays Joan, an artist with a talent for empathy. The film maintains remarkable rhythm.

It opens on the joyous “Gypsy Rondo,” from Brahms’s Piano Quartet No. 1, as a young couple, one a man in a green sweater and jeans, the other a Ken doll in a jogging outfit, meet at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Riverside Park. They are not aggressively claiming their territory in Reagan-era America; they are matter-of-factly appropriating a secular temple in New York as their playground.

Sherwood died in 1990, at the age of 37. You can only curse. What would he have given us had he lived?

*

Sherwood was raised in Battle Creek, Michigan, in what he described as a matchstick house, an appropriate origin for a wunderkind. He had half-siblings from his father’s previous marriage, but his parents treated him like an only child. Kinney has a photo of him, about age six, standing by his straitlaced mother’s side, immaculately dressed in black slacks and a white jacket, wearing a bowtie, a prominent belt buckle, sunglasses, and a self-satisfied smile. “You see in that photo that he’s everything and he already knows it.” A talented violinist, he attended the Interlochen Arts Academy, a boarding school 200 miles north, and while there, he composed a piece for soprano and chamber ensemble set to a text from Finnegans Wake.

When he graduated, he moved to New York to study at Juilliard, but he dropped out in his second year. He couldn’t take the critiques he received from his teacher, the modernist Elliott Carter. “He would look at a manuscript [Sherwood] had labored over for weeks and understand everything inside and out,” Ted Ganger, his roommate from Interlochen, told me. It made him feel small, but Sherwood had also become disenchanted with contemporary classical music in general. It was closed off, academic.

Sherwood was not the first prodigy to explore non-academic life in gay bars. He hung out at the Ninth Circle, a spot in the West Village that collapsed borders, welcoming leather daddies, clones, and tricks. Andy Warhol and Lou Reed were regulars. Sherwood wasn’t exuberantly charismatic, but he was social, and he didn’t identify with any one tribe.

He started off with long hair and torn jeans. The look would be replaced by button-down shirts and sweaters, and sometimes an expensive scarf, but there was always something out of place. Some remember him as polite, others as dyspeptic, a good interlocutor when talking about movies, a control freak when it came to his work.

Although the AIDS death toll had not yet reached its apocalyptic numbers, the threat is felt throughout the film.

He spent his twenties failing better. He drove a cab until he crashed it, and then entered Hunter College, where he studied film production. Over the next ten years, save for an aborted stint in grad school at the University of Southern California, he moved around the city, a place in SoHo with friends, a small apartment in the East Village with his lover—an NYU-educated lawyer who shared his passion for opera—finally settling at 500 West End Avenue.

He made several shorts, among them an unfinished documentary about Elliott Carter and an avant-garde piece titled Variations on a Sentence by Proust that showed on Channel Thirteen. The lawyer moved to London. The relationship and its end provided the basis for Parting Glances.

Parting Glances was made on a budget of about 300,000 dollars raised from friends and acquaintances. Sherwood wrote the screenplay at the CBS offices in Midtown, where he worked as a secretary alongside Kinney, who was then teaching an improv class. Buscemi was performing in a comedy duo act.

The cast was made up of non-union actors, non-actors, and crew members, many of them friends as well. The film was shot on Super 16mm in Sherwood’s apartment on the Upper West Side, a friend’s place in Brooklyn, and the house of another friend in New Jersey, and it was edited by Sherwood himself, alone on a Moviola.

A good independent film is a miracle, requiring loyalty, trust, and goodwill. The makeup person showed up late, and Kinney took over their job. A hairdresser who couldn’t dance played a dancer; Sherwood liked her tattoos. Christine Vachon, now a giant of independent film, synched up the dailies. Sherwood dispatched Elizabeth Karlsen, who at the time had no experience in filmmaking, to go to England to obtain the rights to three Bronski Beat songs he considered essential for the soundtrack. It marked the start of another great career; she later co-produced The Crying Game.

The characters in Parting Glances aren’t that different from the people who made it. Sherwood noted that by the mid-80s, the culture he had discovered in his early twenties had entered the mainstream: the continuous-disco dancing that had been invented in the early 70s at Limelight, a club on Seventh Avenue South; the “Downtown Look” of narrow ties, narrow lapels, and Ray-Bans; and the West Village style of short hair, 501 jeans. The leads in Parting Glances work solid jobs, but they also write, paint, and make music. They go to dinner parties and loft parties, and they are fun to talk to. Semi-professional, semi-bohemian, they do not fetishize their place in the demimonde.

Although the AIDS death toll had not yet reached its apocalyptic numbers, the threat is felt throughout the film. The plot centers on a love triangle, involving Michael, Sherwood’s stand-in, an aspiring writer from the Midwest, played by newcomer Richard Ganoung; his boyfriend Robert, a UNICEF worker headed to East Africa, played by future soap opera star John Bolger; and Buscemi’s Nick, whom Michael cares for.

And though the disease has transformed relationships and sexual mores—a straight friend notes that gay men have become puritanical—the grim, bitchy sense of humor is eternal. After several men reject his advances, a wealthy aesthete declares, “I have the last laugh. I may have committed the gay cardinal sin of being a bit overweight, but it was my so-called unattractiveness that spared me from the plague.”

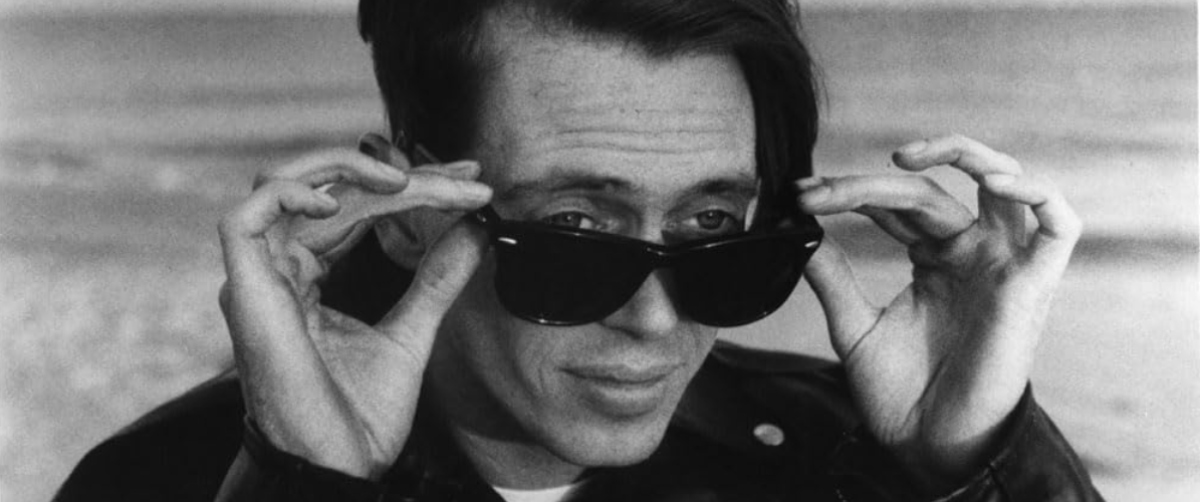

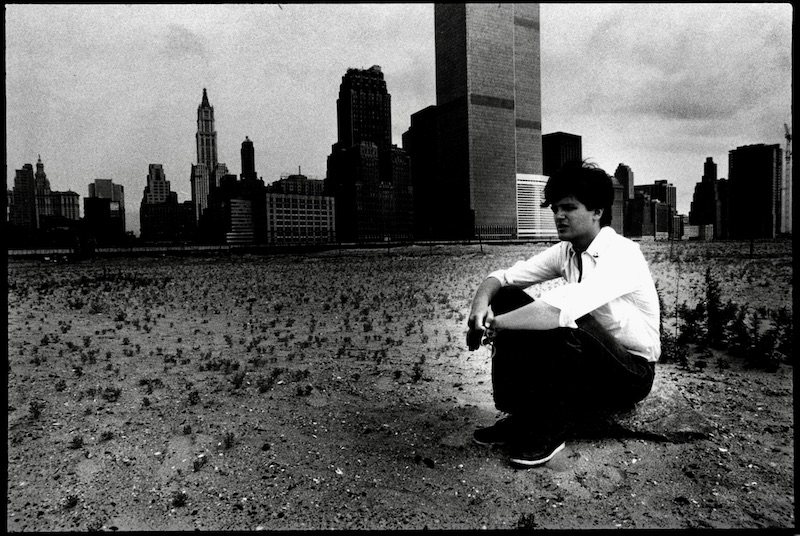

Bill Sherwood in 1981. Courtesy of Johan Edström.

Bill Sherwood in 1981. Courtesy of Johan Edström.

Parting Glances is not Querelle or, for that matter, Variations on a Sentence by Proust, and it doesn’t anticipate the New Queer Cinema of the 90s. Sherwood is partial to the two-person shot, capturing quiet interactions between lovers, adversaries, and friends. The editing isn’t rushed; Sherwood gives his characters both time and space to reveal themselves on their own terms.

In a party scene, he has a naturalistic sense for figure placement, as men and women, gay and straight, casually dance with each other and change partners. There are a couple of “mixed-media, neo-expressionist, post-modernist something or others” in attendance, and one of them, played by Ganger, wants to put on a show featuring AIDS patients. He is one of the film’s few villains. You don’t respond to a catastrophe with cerebralism, the movie tells us. There is an ethical motive for Sherwood’s narrative and formal conservatism, and his gentle touch.

In the best scene, Nick sits in a stairwell, smoking cigarettes with a Columbia freshman. Their dialogue is a duet between the young and the prematurely aged. The kid came out at 16, he tells Nick—he does an impression of looking at his dick in puberty, asking it what it wants—and he talks about a future with a lover, a co-op on Central Park West, a BMW, and a house in Bucks County. “Jesus, next thing you’re going to tell me is you’re a fucking Republican,” says Nick. The kid is half-joking, and he is curious about the lost city of the 70s. Buscemi is restrained. His Lorre eyes, sharp features, and quiet smile are a comedic mask for his sorrow, and he turns down the kid’s request to show him the Village.

The collective memory of the terrible decade is a beautiful man transformed into a near-corpse, treated as an untouchable. Sherwood found another, equally devastating way to describe the robbery of youth.

Parting Glances was not a hit in its hometown. In The New York Times, Janet Maslin called it “a parade of homosexual stereotypes.” Critics and moviegoers preferred Stephen Frears’s London-set My Beautiful Laundrette, starring Daniel Day-Lewis, which played alongside it at the Embassy 72nd Street Twin. (Sherwood’s thin skin is endearing. “I want New York work to be recognized in New York, fascist-geek shithole that it is,” he wrote.) Parting Glances found its fans elsewhere. Richard Ganoung, who had moved to Los Angeles, spotted John Hughes in the audience at the Beverly Hills Cineplex. The film made a small profit, and Sherwood cut a check for everyone involved in the production.

During the final years of his life, Sherwood supported himself by writing screenplays on commission and doing television development, all while planning the films he wanted to make. In his papers, you can find an awful draft for a Madonna/Mikhail Baryshnikov vehicle and enraged letters to The Village Voice regarding its coverage of gay culture and film.

He collected Oriental rugs. “I’m st[r]uck by how rich, lustrous, tactile and almost edible (!) they can be,” he wrote. “Their physical ‘presence’ is almost strangely narcotic.” He obtained experimental medications from an underground health group and later hired a gourmet chef. He talked to only a few close friends about his symptoms. Knowledge of his declining health would have hindered his ability to get work.

Sherwood had an extraordinary career ahead of him, but the greatest tragedy is that he didn’t get to take a risk and fall flat on his face.

Sherwood made several pilgrimages to California, and he met with producers, following one promising lead after another, hoping to get one of his screenplays made, to direct another film. “In classic Hollywood fashion, they’ll probably all fall through and I’ll wind up making a documentary on Ancient Anatolian Carpets in the Collections of Hungarian Lesbians,” he wrote. By 1988, he had made progress on two projects: the first, a dark military comedy in the tradition of M*A*S*H, the second a comedy set in the world of classical music.

Lynn Hendee was a young producer in Los Angeles when she met a man at a dinner party, a Brooklyn-raised Italian who had come out while on duty in Vietnam. The story upset the coming-of-age gay narratives as Hendee understood them. She asked the man to write a biography of his time in the service. A fan of Parting Glances, she approached Sherwood, who would go through several drafts of a screenplay titled Pogues.

The title is derogatory military slang for both gay men and non-combatants. Accordingly, the screenplay tells the story of two men, Tony, an Italian modeled on Hendee’s friend, and James, an effeminate Southern aristocrat, who enlist in the Army and find themselves in Southeast Asia doing secretarial work in a post office. Many of the gags involve James’s refusal to accept the closet, declaring to his C.O. his love for Judy Garland and Barbra Streisand. In the film’s comic high point, he confronts Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and his wife. “Now I’m just curious, did you buy that Yves Saint Laurent jumpsuit with your husband’s heroin money—or are you just a high-priced hooker?” he asks the latter.

At the time Sherwood was writing Pogues, Hollywood was producing several films about the Vietnam War, each of them expiations of national guilt. Pogues tells us, explicitly, that there are gay people whose names can be found on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Although camp humor calls traditional notions of heroism into question, the film still honors basic decency.

Sounds Like This, a meditation on what it means to abandon a vocation, is a more complicated, abstract film. It is the story of Charles, a middle-aged conductor who lives in a state of indecision, declaring his love for Tchaikovsky while acknowledging his futility as a defender of the classical-music faith in the late 20th century. “Tell me, God—why was I not born a black jazz singer?” he asks. “Why did Billie Holiday get to be a genius and I only a dismal arm-flapper…?”

Sherwood never really gave up music. He just changed instruments, and as such, Sounds Like This would have had a remarkable soundscape. As with Parting Glances, he is particular in his choice of music. There is some evidence in the screenplay that Sherwood was planning an MTV for classical music, in which Ancient Roman chords, Mozart, and the greatest hits of 19th-century Europe bleed into one another, against two settings, late-80s New York and an academy modeled on Interlochen.

You don’t respond to a catastrophe with cerebralism, the movie tells us.

But more than anything else, Sounds Like This would have studied the question of reproduction. If one is not to have progeny, must they choose art? A friend rebukes Charles’s ambivalence. “I prefer people who create things—solid evidence that they were here. People who invest everything in their children are pathetic—that’s what dogs and cats do…”

Charles has an illegitimate son who has inherited his biological father’s musical gifts, but Charles is, at best, a kind mentor to the boy, with no real-world responsibilities. In other words, Sherwood doesn’t offer a solution for what was, until recently, a central conundrum of gay life.

Kinney has been working on Future Perfect, a screenplay Sherwood shopped shortly after the release of Parting Glances. (As of now, no one knows who owns the rights.) It’s a whimsical film about a den mother of a house of eccentrics in New York who finds a secret passage in a basement that leads her to Rome, where she strikes up a romance with a local. Sherwood wanted Shirley MacLaine and Marcello Mastroianni for the leads, and Kinney and Buscemi for supporting roles. The film is a madcap fantasy, invoking the dark basements of every New York apartment building and an American’s fantasy of European life.

Sherwood had an extraordinary career ahead of him, but the greatest tragedy is that he didn’t get to take a risk and fall flat on his face. I can imagine several versions of Sounds Like This. I want to see the one that doesn’t quite work, the one that reveals just a little too much of Sherwood himself, the angry, arrogant, playful, glorious artist that he was.

*

Kinney drove Sherwood around on one of his trips to California, for what proved a short, unhappy stint as a director on the primetime series Thirtysomething. “I think he knew he didn’t have as much time as he wanted and he didn’t want to waste it working on this heterosexual show,” she told me. He mentioned to her that he had a sore throat and a hard time eating, but Kinney did not make the connection to the disease that would kill him. He had good money at that point, and before he left, he bought her a pair of expensive sunglasses as a parting gift. It was the last time they saw each other.

On another trip, he stayed with Ganoung and his partner at their place in West Hollywood. Sherwood grew frustrated at some point, and he asked his hosts to take him somewhere, anywhere outside the city, and so they drove out to the poppy fields of Antelope Valley. “I look back and I’m like, ‘Is that when he found out he was positive?’” Ganoung told me. “Or ‘Was this where he got a rejection?’ Or ‘When he was told, “Look, you either join a union or we’re not going to produce your screenplay” or “I’m sorry your screenplay is a piece of shit”?’ I don’t know. I never asked him.”

Ganoung was simply present, a quiet support for whatever it was Sherwood needed in that moment. He sobbed when he told me this story. “I believe good people do that.” They were, in their own way, re-enacting the dynamic between Michael, who had been based on Sherwood, and Nick, whose story Sherwood was now living.

Sherwood didn’t talk much. He looked out at the poppy fields, melancholic as he had a right to be, with friends who cared for him. His final months were an agony and his funeral in Michigan inadequate to his memory. A memorial service was held in New York. Hunter College put on a retrospective of his work, including his short films, and every few years, one film festival or another has hosted a screening of Parting Glances. I’m ending the story in Antelope Valley, noting that Sherwood got back to the city and got back to work, determined to make another movie that mattered.

___________________

Special thanks to Johan Edström, who shared with me much of Bill Sherwood’s papers. Thanks as well to Yolande Bavan, Patrick Dillon, Ted Ganger, Richard Ganoung, Dan Haughey, Lynn Hendee, Elizabeth Karlsen, Kathy Kinney, Jacek Laskus, Peggy Rajski, Lewis Saul, Renato Tonelli, Richard Upton, Christine Vachon, and Angela Yanovich for sharing their memories of Sherwood. The family of James Flannan Browne provided invaluable assistance as well.

Paul Morton

Paul Morton is a writer based in Chicago. He has a PhD in Cinema Studies from the University of Washington, for which he wrote a dissertation on the Zagreb School of Animation. His work can be found in Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, and Full Stop. His email is paulwilliammorton@gmail.com.