Parole For Pay: How America's Criminal Justice System Was Slowly Privatized

Vincent Schiraldi on the Unholy Marriage of Fiscal Conservatism and Law and Order

When Thomas Barrett stole a $2 can of beer from an Augusta, Georgia, convenience store in April 2012, he knew he was at fault.

“I should not have taken that beer,” Barrett told National Public Radio. “I was dead wrong.”

As wrong as it is to steal, no one could have guessed that that beer theft would land Mr. Barrett on private probation, costing him over $1,000 in fines and fees, and that he’d ultimately wind up in jail for twelve months for being unable to pay those crippling costs.

Before any of this, Thomas Barrett was a pharmacist who became addicted to the drugs he was dispensing. His drug habit cost him his job, his family, and his middle-class life. He also started having run-ins with the law, mostly related to public drunkenness.

Barrett had been homeless until shortly before he stole the beer. By that fateful day in April 2012, he had landed a subsidized, $25-a-month apartment. Food stamps were his only regular source of income. Even with his rent subsidy, Barrett had to regularly sell his blood plasma to pay the rent.

When he was arrested, he refused to be represented by the county public defender because even indigent defendants in his county pay $50 for defense costs for people too poor to hire their own attorneys. He was fined $200 and sentenced to twelve months on probation with electronic monitoring. All this was to be supervised by the private probation company, Sentinel Offender Services, at a steep cost.

Fees and privatization are a near-inevitable outgrowth of the colliding forces of budget tightening and supervision expansion.

Although Mr. Barrett had been sentenced to probation, he spent almost two months in jail initially because he was unable to pay Sentinel’s $80 startup fee. Eventually, he convinced his Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor to pay his initial fees, freeing him from jail.

Once he was released from incarceration, the costs of his semi-freedom started to stack up. The electronic monitor cost him $12 a day, plus he had to pay $39 a month to be on private probation, totaling around $400 a month—a pretty steep monthly bill for most people, even more so for a guy who had to sell his blood to pay his $25 monthly rent. Eventually, it all became too much for Thomas to handle.

“Basically, what I did was, I’d donate as much plasma as I could and I took that money and I threw it on the leg monitor,” Barrett said. “Still, it wasn’t enough.”

He started skipping meals and doing without some essentials like laundry detergent and toilet paper. But missing meals left him weak, sometimes making him unable to sell his blood. By February 2013, he had fallen $1,000 behind in his fees, five times his original $200 court fine.

Sentinel filed a technical violation on Barrett for failing to keep up with his fines and fees. His judge sentenced him to a year in jail for the violation.

“To spend 12 months in jail for stealing one can of beer?” he continued. “It just didn’t seem right.”

As the number of cases processed by this country’s police and courts and supervised by probation and parole has exploded during the era of mass supervision, policymakers have been reluctant to fully finance their punitive zeal. This has contributed to growing fees charged to justice-involved people for the costs of court processing, defense, prosecution, jail, and probation and parole supervision, among other things. “Offender” or “user” fees help support the system of punishment that has mushroomed over the last four decades. They can also turn a profit for cash-strapped communities, supporting general governmental operations that have grown dependent on extracting fees from poor defendants to support functions unrelated to the justice system.

Paying to be on probation has flourished in small towns throughout the South (where private companies often receive the proceeds) as well as in big cities (where more often the recipients are government probation or parole departments). As elected officials campaign on tax cuts simultaneous with “tough-on-crime” measures—the latter fueling a system’s growth, the former starving it of resources—something has to give. Probation and parole find themselves caught in the middle, providing bare-bones supervision for an oft-disdained group of people who have broken the law, while trying to avoid the risk that reoffending poses for their elected official bosses. Fees and privatization are a near-inevitable outgrowth of the colliding forces of budget tightening and supervision expansion.

Probation and parole departments in more than forty-eight states now charge people for their supervision. All but one state allow or require the costs of electronic monitoring to be passed on to those tethered against their will to such devices. Over a thousand separate courts assign supervision of people convicted of misdemeanors to private, for-profit probation companies. Hundreds of thousands of people are supervised on privately run probation annually in the United States. A 2014 report by Human Rights Watch found that “the day- to-day reality of privatized probation sees many courts delegate a great deal of responsibility, discretion and coercive power—sometimes inappropriately—to their probation companies.”

Thomas Barrett’s home state of Georgia has been called “the epicenter of the private probation racket.” In 2012, 648 Georgia courts assigned more than a quarter of a million cases to private probation companies. In 2014, thirty-two companies supervised two hundred thousand people on probation in Georgia. About 80 percent of Georgians convicted of misdemeanors who were sentenced to probation that year were supervised by private probation companies. Those companies collected $40 million in fees from people often convicted of low-level offenses such as illegal lane changes, running stop signs, drunk driving, and trespassing.

While charging for probation supervision—public or private—is increasingly common, private probation systems are especially problematic. Because of the loose due process protections for people under supervision described in earlier chapters, probation officers employed by these companies have enormous influence over their clients. This is bad enough when such arrangements come with inadequate protections that deprive people on public probation of their liberty. It’s worse when what limited accountability that might exist is nearly eliminated by the privatization of supervision.

Private companies have a profit motive to expand conditions, lengthen probation terms, and incarcerate their charges in order to extort money out of them and their families. Litigation, government investigations, and reports by organizations including Human Rights Watch have found consistent and widespread patterns of all three types of abuses. Private probation clients are often ordered to wear electronic monitors or take drug tests (whether they struggle with substance abuse or not) at the discretion of the very companies who charge for such “services.” This happens in some cases whether or not the court has ordered such conditions. In some jurisdictions, private probation companies have been delegated enormous discretion to have warrants issued for their clients’ arrest when they fall behind on payments, jailing those clients while they contact their families to solicit payments for their mounting debts. As with Thomas Barrett, the debts for supervision, electronic monitoring, and drug testing can amount to several times the initial fines levied by the courts.

Pay-only probation directly contradicts the goal of probation as an alternative to incarceration.

Such companies often make determinations as to whether individuals before the court have the ability to pay their fines and fees. This is a direct and obvious conflict of interest for private probation companies and their employees, some of whom receive bonuses on the basis of how much money they extract from their clients. For example, in a 2013 deposition in litigation against Sentinel Offender Services, Mark Contestabile, a Sentinel official, said that his employees receive bonuses if they reach their forecast targets. Contestabile related that his $179,000 annual salary was increased each quarter by $6,000 if the company met its financial targets.

Often, people supervised by these private companies find themselves on “pay only” probation. Pay-only probation is reserved exclusively for economically vulnerable people. If a defendant appears in court and is ordered to pay a fine and they can pay it, their matter is satisfied and they go on their way. But if they are unable to pay the amount the court has levied, they are put on probation exclusively to pay the court fine; hence, pay-only probation. Often, their probation fees equal or exceed the monthly fine payments they make, doubling and tripling their original costs. Not only can the requirement to pay fees be the sole reason for placement on probation, but supervision can be extended far beyond its original term until fines and fees are paid off. Pay-only probation directly contradicts the goal of probation as an alternative to incarceration and is the clearest possible example of net-widening because, in such cases, probation isn’t an alternative to incarceration, it’s a fee-collection vehicle.

It can be difficult to understand why the U.S. justice system deliberately charges people to be on probation or parole, when it is obvious that most of them simply do not have the means to pay. Charging people could drive them to commit more crimes. It could change the role of a probation or parole officer from one intended to be centered on rehabilitation to that of bill collector, which in turn significantly perverts the relationship between POs and the people under supervision. Or, the fees could drive people to skip their supervision appointments, prompting the judicial system to lengthen supervision or make it more punitive and less forgiving. Ultimately, it could result in incarceration—a failure for a community supervision program designed to keep people in the community—an outcome that is far more costly to the jurisdiction and, in a very human way, to the people on supervision and their families.

________________________

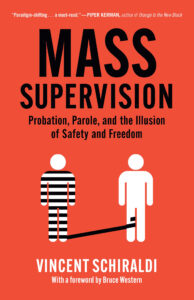

This excerpt originally appeared in Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom by Vincent Schiraldi, published by The New Press. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted here with permission.

Vincent Schiraldi

Vincent Schiraldi is the founder of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice and the Justice Policy Institute. He has served as director of juvenile corrections in Washington, DC, commissioner of the New York City Department of Probation, and commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction. He has been a senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and co-founded the Columbia University Justice Lab. He is currently secretary of the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services and has written extensively for outlets ranging from the New York Times to The Marshall Project. The author of Mass Supervision (The New Press), he lives just outside of Washington, DC.