The zone.

The Zone is gradually disappearing, like a grease spot being vigorously rubbed. At Porte de Pantin, through the mounds with chalky paths running down their sides that mark the site of the old fortifications (quite invisible today), workmen are carving out a railroad-like trench for a planned expressway. The tumultuous city advances, gnawing away at the chlorophyll-deprived vegetation. It is advancing so quickly that a mobile home up on blocks now seems like an anachronism. On the far side of Boulevard Mortier, very tall and very dull modern buildings are the bounding walls of a new prison. The bus that crosses the waste ground is aerodynamic, and its sliding doors scatter the sparrows. They are replacing the elbow gas lamps on Rue Paul Meurice. Roadways Department men are digging channels for black pipes that gape like cannons. In Rue des Prévoyants an insurance agent is meticulously examining the façades of the houses.

But all along the sinuous Avenue du Belvédère red saucepans hang like fruit from the branches of the bushes. Between Porte des Lilas and Porte de Bagnolet you still find that archaic amalgam, a community of ragmen, scrap-metal dealers, chair bottomers, panhandlers, raisers of poultry or of white mice, ensconced in a patchwork of uncultivated plots and shacks separated by hedges of folding bedsteads (remarkable by their number), dwellings constructed more of wood than of concrete, more of boards and sheet metal than of brick, structures whose purpose is not immediately apparent: cabin, toolshed, rabbit hutch, outhouse? Amid cabbages and sunflowers, bathtubs do the job water towers do in the rich suburbs, but we are in the Twentieth Arrondissement. Two or three trailers stand on wooden piles that are beginning to vanish into the earth, having been in place since before the war or before the exodus. An old truck painted pink and brown, like fairground spicebread, has a hooked nose of a front end, white curtains at the windows, and greasy yellow smoke rising from its roof by way of a cowled chimney. It is Monday. There are no kids in Rue des Fougères, nor in Rue des Glaïeuls, only flowering yucca beneath damp garments fluttering on clothes lines. An old fellow is rinsing lettuce at a fountain whose pipe is bound up with straw. An old woman is tearing down the boards of a fence with a hatchet and chopping the wood small by the gutter. The paths are muddy and full of dandelions and the lots are dotted with unproductive Brussels sprouts.

I go over to Francis’s place to buy three Gauloises at four francs fifty each. This dive, like the hovels nearby, is crammed into a hollow, crouched beneath its roof of planks and tiles (an obvious luxury), and no larger than a place to doss, most of the room taken up by the bar and a roaring Godin stove with a silver-painted chimney pipe. The low ceiling is full of holes plugged with paper. Between the boards underfoot you can see and smell a mud floor. In a recess are three little tables and a banquette where it is pleasant on Sunday evenings to eat Madame Jeanne’s pot-au-feu, imposing platefuls of which she serves at a price commensurate with her usual clientele, a mix of ragpickers, Gypsies male and female, and the good folks who rent or own the parcels of land hereabouts. This is, as they put it, the only bistro in “the village.” I am at home here. Part of the family. I listen to the boss talk. Old Francis is a former baker who has lost an arm and the use of one leg but not his smile and his ever-ready welcome; also a tramp around 1910, an honorable and fruitful period for knights of the road. We are bosom buddies, Francis and I. I listen to his stories with my legs wrapped around the stove, my belt unbuckled after a substantial meal, a glass of the proprietor’s special-reserve brandy in my fist, all ears for the portraits he loves to paint of the eccentrics of every feather who haunt this patch of the Zone, or for his memories of the good old days (hardly long gone) when the café was a place of “ill repute,” when shootings and knifings came as readily as insults, when Dédé-the-Baker, a notorious counterfeiter, would come and hide in the Beaujolais closet, and when police raids were an everyday occurrence. But those times are fading now, he tells me. The bistro has become cozy, and quieter than a weekend café-dansant on a Monday; and the customers, as I can see, are now all respectable people. No kidding. I acquiesce tongue-in-cheek. What a motley crew! Rose and Madame Noémie are two beautiful Gypsies, well-upholstered and always laughing, who flirt with the men and drink like fish. And then there is Martin, Martin most of all, maybe the only guy in Paris entitled to call himself a water-carrier, because every morning he goes to the fountain, armed with blue ceramic pitchers and battered watering cans, to meet the all-purpose H2O requirements of ten or fifteen locals, performing this service, running this errand for the tobacco seller, the baker, the grocer further away in town on the far side of the barracks, and so on, and getting himself paid for the most part in kind—in cigarettes, in cups of coffee or glasses of wine, or in bowls of soup ordered up in a peremptory tone, for he is not one to hold his tongue; he automatically checks the counter and will not go to fetch needed supplies unless his bowl is filled to the brim in advance and placed in plain view; in short he lives the life of Riley, sleeping in a more or less well-protected hut of which he is the legal owner, early to bed and late to rise, getting to Francis’s place only about ten in the morning (to the despair of Madame Jeanne who has nothing to extend her soup with), greeting the company, clamping his gloved hands to the sides of the stove, approaching the boss, who is at a landlordly breakfast with a salad-sized bowl of café au lait and slices of bread and butter, and declaring, with a provocative glance and in a theatrical voice, “Ah! How I love your coffee!”—an envious cry that in no way prevents him from savoring his first demitasse of the day in obvious bliss. Madame Jeanne tells me that yesterday, having taken him to the weekly market so that he could carry her shopping bags, and seeing him shivering with cold, she sought to console him by promising a good hot cup of java on their return, to which he replied, all innocence, “In a bowl?” He was a card, that Martin. Drink brought out an extraordinary eloquence in him, and we were treated to disjointed reconstructions of various stages of his life. He had spent ten years in holy orders, but one day had an “adventure” with a woman, never wished to repeat it, and thereupon cast aside his cassock for reasons known to him alone at the time—and possibly to the said woman. A real card, Martin. The Gypsy ladies teased him, offering him everything, including themselves, and saying they would work to make him rich if only he would marry them, but he would take umbrage and march out, grumbling, leaving the door open behind him, for he was extremely thin-skinned, though he never omitted, before making his exit, to take advantage of a customer’s turned back to polish off the contents of any glass left perilously unattended on the bar, then he would scurry off up the bumpy path outside and the whole room would erupt in a gale of laughter.

The liquid refreshment that made him eloquent also made him sentimental. He would sing sad old songs with romantic melodies and refrains that touched everyone. And rightly so. It was there that I heard the most beautiful ballads and rich in vernacular, perhaps not the best known but extraordinary in their candor and realism, which Martin like the others knew by heart and which never seemed to end, for each one told a true story with many episodes. Night would fall. Old Francis bought a round. People delved into their pockets in search of enough change for the last few smokes of the evening. Good humor reigned. Everyone was their neighbor’s best pal, from Pablo the Gypsy acrobat to Zizi the Rapier, who one night went raving through the vegetable plots about how she wanted to find her girlfriend Mado and cut her throat, and in a dangerous state of inebriation rooted through every nook and cranny where Mado might be holed up in fear of Zizi’s reprisals for an illegitimate dalliance. Mado ran among the fences until, exhausted and frightened to death, she took refuge at Francis’s place, only to come face to face with the vindictive Zizi. Fortunately the boss had the presence of mind to toast the armistice, and the antagonists reconciled in a clammy embrace.

Truly a fabulous bistro, where the excellent bottled wine was cheaper than the plonk on offer elsewhere. I would happily have lodged there had there been a room for rent or even the corner of a shed. I dawdled until closing time—around ten or eleven o’clock, the regulars being earlier risers than me. Only old Francis was still there, dragging on a cigarette, a habit that gave him an incessant little cough and a sniffle that had nagged him since the last war but one, and his wife doing her sewing, that old beggarwoman sucking up her umpteenth red, bundled up in her clothes and far better there in the warm than stretched out in her bed alongside her cold bowlegged husband; she started making heavy rolls out of imposing heaps of change spread across the oilcloth, her day’s takings gleaned in the passageways of the metro, where she feigned selling needles and thread so as to remain within the law but year in year out brought home two or three thousand francs a day (quite enough to raise eyebrows among all those allegedly unprejudiced and pseudo-charitable souls who live in a townhouse and run a car—and not a clunker such as the rabbit-skin sellers drive, but a solid family Peugeot). In this way she supports her man and has enough left over to go with him every Saturday night to Les Halles, where the pair enjoy a slap-up meal and empty seven or eight bottles of Alsace between them, which by break of day puts them in the jolliest mood and fills them with confidence for the future.

Which is all well and good, but now it is eleven o’clock. The winter night bars the way to any reasonably protected resting-place. All the same, I have to shake a leg. The cold hardens the ground and loosens the socks. Despite (or rather because of) the warm intimate atmosphere I am leaving, solitude makes my mind a blank. Where to go? Behind me, as he bids me goodnight, which is kind of him, old Francis closes his door and turns the light off. He is going up to his bed, in a room with no fire but out of the wind, to slip between sheets which, freezing as they may be, will nevertheless husband his animal warmth. Of course, I could always have discreetly conveyed to him that three of his bistro chairs arranged for a few hours around the still warm stove would have constituted a precious contribution to my circuit of the city. But one has one’s dignity (strange to say), and Francis takes me for a “straight arrow” despite my fuzzy jowl and tangled hair, and he has never asked me how I spend my time, just a few polite enquiries about how I am getting along with my everyday problems. So here I am, nonplussed, alone in a silence that bodes nothing good. Fortunately, I have smoking materials, including matches, in my pocket, and I roll myself a cigarette. Once my eyes adjust to the darkness, I set off along Rue des Fougères. It is definitely too cold to sleep under a hedge, and I reach Porte des Lilas without solving my problem. Another moment of indecision. Should I go down beyond Ménilmontant and towards the Buttes, where there is no shortage of hidey-holes, or stick to the Zone as far as Porte de Pantin and make my way to the coppiced huts inhabited by clochards? But the cold grips me by the shoulders and forces me on down Rue Saint-Fargeau. And there it is: I’m on my way. The spring is back in my step, I gather a few butts by way of provision for the night, and fairly hop, skip and jump myself into Rue des Cascades. Another magnificent neighborhood, with street names inherited from the former high-perched village traversed by brooks—Rue des Rigoles, Rue de la Mare—streets twisting and turning this way and that, quite unlike the broad and endlessly long avenues lower down, which are the bane of bums. Up here the distances are shorter, and almost too soon for my liking I am in Rue Fessart. Climbing the railings of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont is out of the question: the cold would chase me out quicker than any cop. The empty lot of the old Pathé film studios is likewise impractical. But I know some priceless places to flop behind some garages. I climb. I go over a couple of walls, and now I am chez moi, in a courtyard at the far end of which are sheds that are never locked, ragmen’s storage places where I can settle in, snug as a bug in a rug, among piles of paper and sacks. I chew on my last bite of the day, spit it out, and so to bed. The trick is to wake before daybreak, before the arrival of the fleamarketers, who take a dim view of intruders.

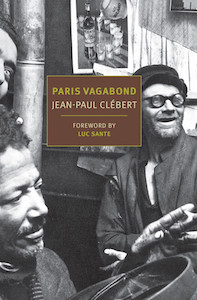

From PARIS VAGABOND. Used with permission of NYRB. Copyright © 2016 by Jean-Paul Clébert.