“Paris is Paris. There is But One.” On Van Gogh’s Painterly Relationship to France

Gloria Fossi Shares Settings Where the Painter Made His Mark

“And mind my dear fellow, Paris is Paris. There is but one Paris and however hard living may be here, and if it became worse and harder even—the French air clears up the brain and does good—a world of good.”

(Paris, September–October 1886. To H. M. Livens.)

Vincent Van Gogh had arrived in Paris in late February 1886. He was writing to Horace Mann Livens, a young English painter he’d met at the Academy in Antwerp while practicing on gypsum casts of ancient sculptures. The letter, which sold at auction in 1995 and is in a private collection, is a rare testament to Vincent’s time in Paris: only ten letters document the two years he spent there.

In this first letter, Vincent talked about his new landscape studies, “frankly green, frankly blue.” He said that since life is found in color, “true drawing is modeling with color.” He reiterated his respect for all-stars like Delacroix and mentioned artists he’d never heard of before—peers or people not much older than himself. In Antwerp, he hadn’t known about the impressionists. Now, he told his friend that he wasn’t “one of the club” but that he admired Degas’s nude figures and Monet’s landscapes. But Vincent hadn’t moved to Paris to join the impressionists.

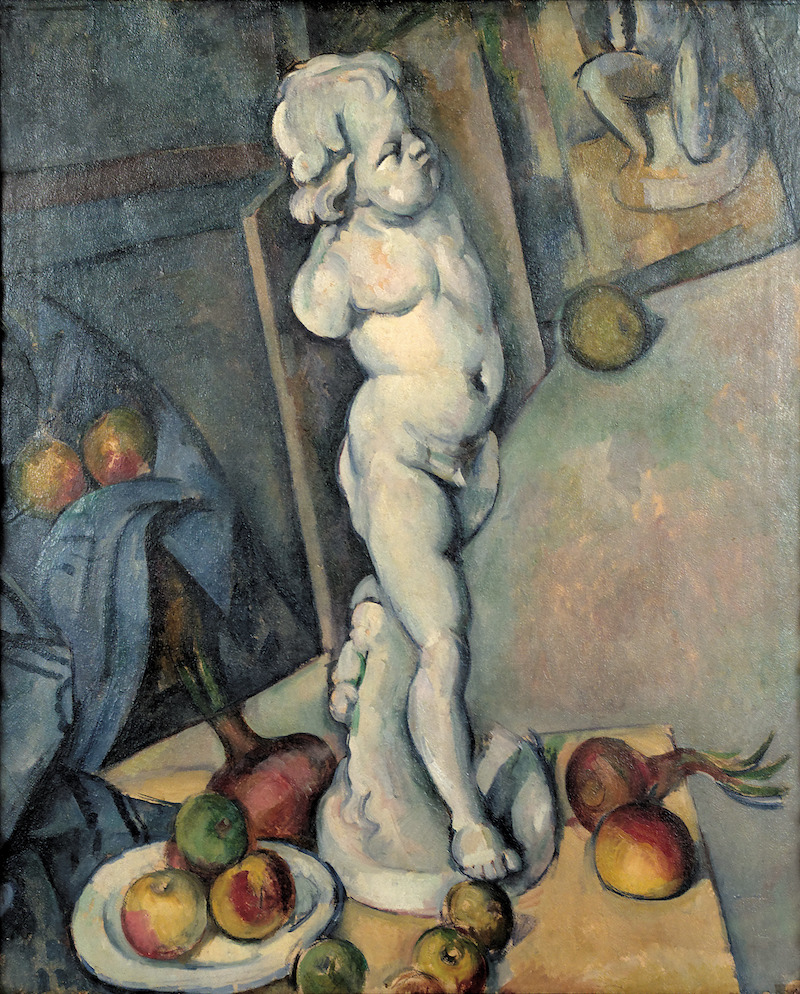

His three months in Antwerp had been miserable, economically and physically. He’d failed to work with live models or find women who would pose naked, so he’d settled for gypsum casts—a common practice in the academies. He also used casts while working at home in Paris. He owned a few small casts of ancient Venus figurines, which led to sketches, drawings, and eventually to sublime still lifes—like Still Life with Plaster Statuette, a Rose and Two Novels and Plaster Cast of a Woman’s Torso. These seem to have predated some of Cézanne’s similar experiments, such as his L’Amour en Plâtre (1895), now at the Courtauld in London. The tradition of inserting casts or statuettes into larger paintings has been alive and well since the Renaissance. It took on new life after Vincent’s experiments, and then, after Cézanne’s practice, with artists like Matisse and Picasso at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Plaster Cast of a Woman’s Torso (Paris, February–March 1887). Oil on canvas, 40.8×27.1cm. Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Plaster Cast of a Woman’s Torso (Paris, February–March 1887). Oil on canvas, 40.8×27.1cm. Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Antwerp had dashed Vincent’s hopes of selling his work. But in Paris (which he’d already visited in 1873 and 1875), he was exchanging paintings left and right, and becoming fast friends with new artists. He also tried to sell some of his paintings for 50 francs each, through several different dealers, but to little avail.

Paul Cézanne, L’Amour en Plâtre (1895). London, Courtauld Gallery.

Paul Cézanne, L’Amour en Plâtre (1895). London, Courtauld Gallery.

To Vincent and his peers, Paris was the quintessential modern city. It was the home of grand boulevards and train stations in cast iron, of guinguettes (typical open-air bars and restaurants) and cabarets and mills turned into dance halls, of bridges and picturesque river views. It was the setting of Maupassant’s and Zola’s naturalistic novels. Its galleries and vibrant art markets attracted throngs of painters from around the world and a few art critics as well. Above all, it was Theo’s city.

In 1882, he’d been promoted to art director at the former Goupil & Cie Gallery at 19 Boulevard Montmartre. The business had since become Boussod & Valadon, and Theo was spearheading the move to add impressionist painters to its widening repertoire—in direct competition with the impressionist dealer of choice, Paul Durand-Ruel. Theo had keen acumen and saw great potential in avant-garde art, though Goupil’s more traditionalist bent favored painters like Millet, Delacroix, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Daubigny: the same artists being sold by other Parisian art dealers at “exorbitant prices,” as Vincent said in his letter to Livens. (Paris, September or October 1886. To H. M. Livens.)

Theo was supportive of Vincent’s planned move to Paris, but he also had reservations. At the time, Theo was living at 25 Rue Laval (now Rue Victor Massé), in an elegant building that combined neo-Gothic and neo-Renaissance styles. His neighborhood lived and breathed art in all forms. Maurice Ravel lived a few feet away. Down the road was the Bal Tambourin, one of Vincent’s chief haunts, and the famous cabaret Le Chat Noir. H. Vieille’s store, which sold canvases and frames, was in the same neighborhood, and in the 1870s, the American impressionist Mary Cassat had had a studio nearby.

Paris, 54 Rue Lepic, VIII arrondissement Vincent and Theo moved to the fourth floor of this building in June 1886. Vincent stayed here until leaving for Arles on February 20, 1888. He often painted wide views of the city from his window.

Paris, 54 Rue Lepic, VIII arrondissement Vincent and Theo moved to the fourth floor of this building in June 1886. Vincent stayed here until leaving for Arles on February 20, 1888. He often painted wide views of the city from his window.

But Theo’s apartment was too small and not an ideal space for painting. So he asked Vincent to detour through Nuenen and stay there until June, giving him time to find a better living arrangement for them. But without warning, Vincent landed in Paris like a meteor on February 28, 1886 (or the day before). He’d been drowning in debt in Antwerp and left without settling it, as he later confessed in a letter. As soon as he arrived, he ripped out a page from his notebook, wrote a message in French, and sent it to his brother at the gallery. This important piece of history may have survived because, about a month later, Theo jotted down a laundry list on the back of the page. Vincent’s message was resolute, with a touch of anxiety:

“My dear Theo, Don’t be angry with me for arriving out of the blue. I’ve given it so much thought and I’m sure we’ll gain time this way. Shall be at the Louvre from midday onwards, or earlier if you like. Please let me know what time you can get to the Salle Carrée […] come as soon as you can.”

(Paris, around February 28, 1886. To Theo.)

Montmartre the Quarry and Windmills (Paris, June–July 1886). Oil on canvas, 32x41cm. Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Montmartre the Quarry and Windmills (Paris, June–July 1886). Oil on canvas, 32x41cm. Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Theo welcomed him, of course. The brothers shared the apartment on Rue Laval until June, then moved to a larger place on the top floor of 54 Rue Lepic, halfway up the hill of Montmartre. Vincent’s bedroom opened onto vast views of Paris. Starting then, he painted at least 280 works of art, with new colors and experiments, including still lifes, his first sunflowers, and studies of plaster casts. He also painted dozens of plein air panoramas, for which his model was the picturesque, almost rural Montmartre, with its wide green spaces, its mills surrounded by vegetable gardens, its cabarets and coffee shops. Asnières (now Asnières-sur-Seine), north of Paris, would provide a similar model later on.

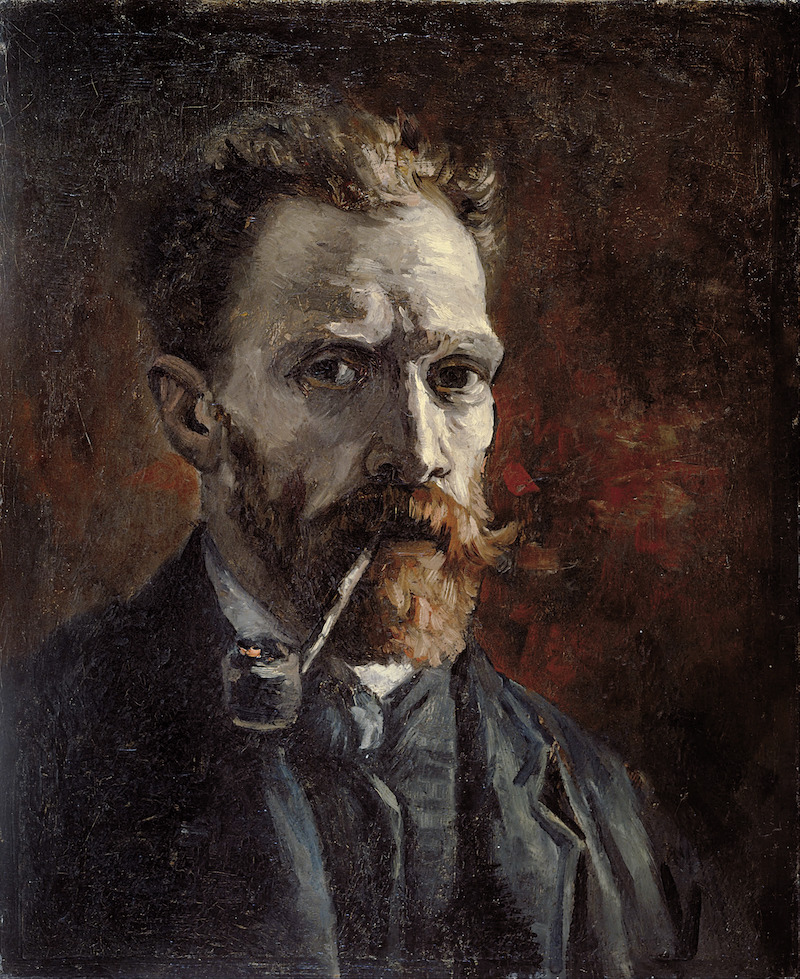

Self-Portrait with Pipe (Paris, September–November 1886). Oil on canvas, 46x38cm. Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Self-Portrait with Pipe (Paris, September–November 1886). Oil on canvas, 46x38cm. Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

One of Van Gogh’s first self-portraits in Paris. He painted himself in traditional clothing, with a pipe in his mouth and looking far older than his 33 years.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Portrait of Vincent van Gogh (Paris, 1887). Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Portrait of Vincent van Gogh (Paris, 1887). Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who was eleven years younger than Vincent,first met Van Gogh at Fernand Cormon’s studio, at 104 Boulevard de Clichy.

Many young artists would congregate there, including Émile Bernard and Georges Seurat. Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh became lifelong friends, their closeness apparent in Toulouse-Lautrec’s intense pastel of Vincent in a Paris café. In January 1890, during the Les XX exhibition in Brussels, Toulouse-Lautrec even came to the point of challenging one detractor of Van Gogh to a duel. Theo had sent six canvases for the exhibition.

Paris, XVIII arrondissement The steep, cobblestone steps leading from Place du Calvaire to Place du Tertre, on Montmartre—one of the most visited spots in Paris. Their charm and poetry made them popular with the avant-garde artists, too. The Van Gogh brothers lived nearby, on Rue Lepic.

View of Paris from Montmartre (late summer 1886). Oil on canvas, 38.5×61.5cm. Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel.

View of Paris from Montmartre (late summer 1886). Oil on canvas, 38.5×61.5cm. Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel.

A view from the “gray” city, as in Zola’s beautiful description.

The windows had almost always been left open; she could not cross the room, could not stir or turn her head, without catching a glimpse of the ever-present panorama.

(Émile Zola, A Love Episode, 1878)

Paris: The modern city as seen from Montmartre, a symphony in gray.

_______________________________________

Excerpted from In Search of Van Gogh: Capturing the Life of the Artist Through Photographs and Paintings by Gloria Fossi, photographs by Danilo De Marco, translated by Elettra Pauletto. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Harper Design.

Gloria Fossi

Gloria Fossi is a medieval and modern art historian.