I prophesied spring’s early arrival. I prophesied the word diabetes in the movie theater, a whole minute before it happened. Is that improbable? Science fictional? No. At age fifteen, I still had a living connection with one element of the childhood world: prophecy. Most people remember nothing of this childhood power.

I have a few theories about why.

First, the prophecies have a very short time horizon—somewhere between two seconds and one minute. That’s not enough time for most kids to put the prophecy into words. And since we tend to remember events that have become entangled in words, it’s not surprising that we forget most or all of our prophetic experiences. Second, and related to the first, the prophecies tend to concern things with minimal social relevance—an acorn about to fall, the imminence of a blue car, a word someone will speak. Such things are of little interest to adults, who act as the gatekeepers for what children will remember, by selecting what internal and external events they ask the child to put into words.

You remember when you had a fever when you were four, be‑ cause Mom noticed you were flushed and asked you how you were feeling. Then she took your temperature and told you it was a fe‑ ver. But a lot of the other strange things that happened in your body—things much more intense and unusual than a fever’s mild hallucinations—entirely escape the sieve of memory.

Yet some circumstances lead kids to both put the prophecy into words and to speak the words to an adult. If this happens, you re‑ member. When I was five, I practiced prophecy as a way of im‑ pressing my babysitter, who I was in love with.

“Courtney,” I said. “I love you.” She looked down at me irritably.

“You need to hold on to my hand, Nicholas,” she said. “Why do I have to tell you every time?”

We were in the middle of the street. I’d wriggled out of her grip. Courtney’s sense of danger seemed to me to be misplaced. Ours was a very quiet street—whole hours could pass without seeing a car. I also frankly doubted that being physically tied to a large, lumbering, slow‑moving adult would help me avoid being hit by a car. The opposite seemed to be true. I had privately re‑ solved that if a speeding car should ever unexpectedly round the corner and bear down on us, I would immediately slip free of whatever adult was holding my hand. But holding hands in the street was the Rule. My little brother held tightly on to Court‑ ney’s other hand.

“You have to hold hands,” Alex said primly, earning him a smile. Nothing would have pleased me better than to hold Courtney’s hand in mine. But not the way we held hands crossing the street. That wasn’t my idea of holding hands. She was holding my hand—more than my hand, in fact. She had a good portion of my arm in her grip. It was the kind of grip people used on luggage, or on bags of trash.

“I can walk across the street fine,” I said. “I’m not like Alex. You don’t have to make me.”

I demonstrated my competence by matching Courtney step for step, not straying an inch. I kept the arm closest to hers tucked behind my back, in case she should try to snatch it. She sighed.

On the far side of the street lay the park, a wide, grassy expanse where no one had ever seen a car. Alex, released from Courtney’s grip, ran off to play in the sandbox.

“What a beautiful day,” I said. Courtney looked at me strangely.

“Don’t you want to go play in the sandbox?”

For a moment I was tempted. The sandbox was a magical place. Four wooden planks separated the earth of the sandbox from the earth of the ordinary world. The actual contents of the sandbox were not, despite its name, all that distinctive. Over the years grass and dirt had migrated into the box, and sand had crossed the bor‑ der going the other direction. But within the frame, matter be‑ came meaningful. Outside the sandbox a pile of dirt was just a pile of dirt. Inside, it was a real pyramid, with priests and pharaohs.

I tore my gaze away from it.

“No,” I said, resolutely. “I am enjoying the beautiful day.”

This was a formula I’d heard my mother use when she didn’t want to move. Courtney shrugged and sat down on the bench, digging her book out of her bag.

*

The March day may or may not have been beautiful, a word whose meaning I wasn’t entirely sure about. But it did hold rare, wild energies. Big white clouds scudded across the blue sky, visible signs of the wind, which was invisible like God, cold, and marvelous.

There would be an interval of stillness. Suddenly the dead air moved, the bare tree branches danced, shivers of excitement passed across the stray pools left from the morning’s rains. The silent solid world began to breathe. Stray pieces of matter—dead leaves or bits of newspaper—rose into the middle air and whirled. Alex, sitting in the sandbox, threw back his head and raised both of his arms. I bit my lip to keep from grinning, stood into the wind like a soldier.

Then it vanished. The world grew ordinary and unmagical again. But you could sense the half‑visible feelers, like the torn bit of newspaper, now trapped in the brambles of a bush, spread like a sail, waiting . . .

“Hey, Courtney,” I said.

“What,” she said without looking up from her book. “I know when the wind is going to come.”

That made her look up. Amusement curled her lip. “Oh yeah?” she said.

“Yes.”

I stood with my arms crossed over my chest, looking back at her. I waited a few seconds, until I felt it. I raised my right hand.

“Now,” I said.

Instantly the wind blew out of nowhere. Wild excitement filled the world. Alex, sitting in the sandbox, raised both his arms.

The wind died.

Alex and I lowered our arms. Courtney blinked.

“Whoa,” she said. She was looking at me quizzically now. “That was a coincidence.”

“What’s a coincidence?” I asked.

“A coincidence,” she said, “is when something happens for no reason.”

I considered.

“What is it called when you know something is going to hap‑ pen and then it does?”

She thought for a moment. “Prophecy,” she said.

“That’s what I can do,” I said. “Prophecy.”

She smiled at me. I raised my hand. The air stood up and rushed around, the white clouds sped, the scrap of newspaper rose into the sky and disappeared in a flash of sun.

The wind died. Courtney’s mouth opened, surprise and the start of belief in her eyes. She was seventeen. Maybe she was remem‑ bering how this worked. All afternoon I prophesied the wind.

When we were ready to cross the street again, she grabbed Alex’s hand. Then she waited until I took her hand in mine.

*

Now I was fifteen, and prophecy had mostly decayed into coincidence. I could still prophesy the seasons, a little. And occasionally other things. Like the word diabetes, which I had prophesied a minute before its appearance in The Godfather III.

It was a word of dark magic, of poisoned time. I’d first encountered it in a book I’d read at age eight, in which a minor character—a child—gets thirsty, is diagnosed with diabetes, and dies within two pages. Since then I’d occasionally recognize in an otherwise blank hour the smile of an old enemy. The word would appear.

I also experienced false prophecies. At lunch period, two days and one and a half hours after Sarah had passed me the note that said “YES,” I sat at my usual table with Ty and Nicole and the others. I was intensely aware of Sarah, who was sitting three ta‑ bles behind me. I wondered if she was watching my back, guess‑ ing the movements of my hands as I ate my sandwich. I sat straight, tried to give my motions a studied insouciance.

“You have food on your face,” Nicole observed.

That was when I had the false prophecy. I suddenly felt absolutely certain that Nicole was about to say “diabetes.” I stared at her. The air went into prediabetic stillness. The seconds flattened and stretched. I felt Sarah’s gaze on the back of my head.

I stared straight at Nicole’s face, waiting. “What,” she said. “The fuck. Are you staring at?”

Misfire. No diabetes. But I couldn’t blink. Neither did she. A feeling of unbearable intimacy developed. Staring at each other, our intertwined gazes like a sliver of ice, sliced off the social gla‑ cier, floating.

“Staring contest,” Ty said.

I somehow unscrewed my gaze from Nicole’s spiral eyes. We both blinked. She looked back at me with quick, darting glances, like her eyes were sore.

“Weirdo,” she said.

“I’m zoned out,” I said. “I haven’t been sleeping too good.”

“You should drink cough syrup for that,” Ty said.

“That’s your answer for everything,” Nicole said.

“My dad’s a doctor.”

“Does he prescribe cough syrup for everything?”

“No,” he said.

Nicole laughed.

“He’s a bad doctor,” Ty finished.

Ty was covering for me. He’d noticed the weirdness, and he was spraying the table with the small‑arms fire of a stupid joke to pro‑ vide cover for me to pull it together. That was the kind of thing that made you love him. On the one hand, he’d humiliate you in public if the mood took him. But that was strictly between me and him, the other people were just amplifiers, devices used to enhance a victory entirely contained within the walls of our friendship.

But when it came to other people attacking on their own initia‑ tive, to Nicole calling me “weirdo,” for example, Ty had utter, in‑ stinctive loyalty. He’d covered for me countless times. Soon I was able to smile again.

“Ty’s right,” I told Nicole. “Cough syrup will cure any disease.”

“It’s just a question,” he said, “of the right dosage.”

“Two tablespoons to fall asleep,” I said.

“Half a bottle cures fever,” Ty said.

“And ten bottles,” said Nicole, joining in, “cures diabetes.” My smile vanished.

“Cures it permanent,” said Ty.

I put the smile back on my face. I got up and walked across the cafeteria toward the bathroom. The fluorescent lights were too bright. I was having trouble with my eyes. They would get stuck, as I was walking. Looking at a spot of tiled wall in front of me, I got stuck in it. Like staring at Nicole, but generalized. Inorganic surfaces became porous to my looking.

I felt my gaze vibrating inside my face. I became excruciatingly aware of the socket of my face, the socket that held my looking: the little fringe of my long hair, the faint brown circles of the frames of my glasses, the flesh‑colored shadow of my nose.

My gaze turned in its socket. I couldn’t control it. It spiraled into that circle of yellow tile wall. Blinking didn’t cut it off. The blinks passed through it like bullets through a column of water.

It started to affect my walk. I was being pulled toward the spot of wall, while I was aiming for the door twenty feet to the right. My head was turned one way, my body another. People will no‑ tice, I thought.

I fumbled for the paper bag in my pocket. Somehow I got my gaze free and pointed the right way. Quick glances, I thought. That’s the key. That’s the secret. Quick, fast glances and the seri‑ ous stare doesn’t develop, the gaze doesn’t get stuck.

And now I was worrying about whether it was real, whether the gaze‑getting‑stuck thing was even real, whether anything real had happened between me and Nicole, whether it was a weirdness that had a name, or whether it didn’t have a name and would dis‑ appear on its own.

Fuck diabetes, I thought.

I got into the bathroom. Dull mirror and drab metal passed sickly fluorescence between them. Thankfully there was an empty stall. I kicked the seat down, then kicked the toilet paper roller hard with my foot so it sounded like I was getting a whole lot of toilet paper, effectively masking the sound of me unwrinkling my paper bag. If people were listening, I thought, they could think I needed a lot of toilet paper. They could think I had diarrhea. The word would go into their heads and disappear. It was a self‑erasing word. The opposite of diabetes.

Then I had the bag to my face and the carbon dioxide was expanding my lungs and my thoughts were slowing. I forgot that my gaze was lodged in a socket of flesh, a socket of thingly substance. The frames of my glasses no longer stood out against my vision as alien.

It’s just a reaction, I thought. Everyone has words that are bad for them.

My breath came slower now. The bag de‑ and re‑flated calmly and regularly, with the unurgency of a domestic machine. A lawnmower, a vacuum cleaner. I lowered the bag.

I sat on the closed toilet seat with the paper bag loose in my right hand, breathing slowly, a smile growing on my face. I was thinking about Sarah. I was thinking how easy it would be. I could just walk up to her, take a few hits from the paper bag, and then ask her for her phone number. Or where she lived. Maybe I could ride the bus over there, if it was too far to bike. I had a feeling she didn’t live close to me. We could go to a park, if the weather was nice. I could ask her what kind of music she liked.

__________________________________

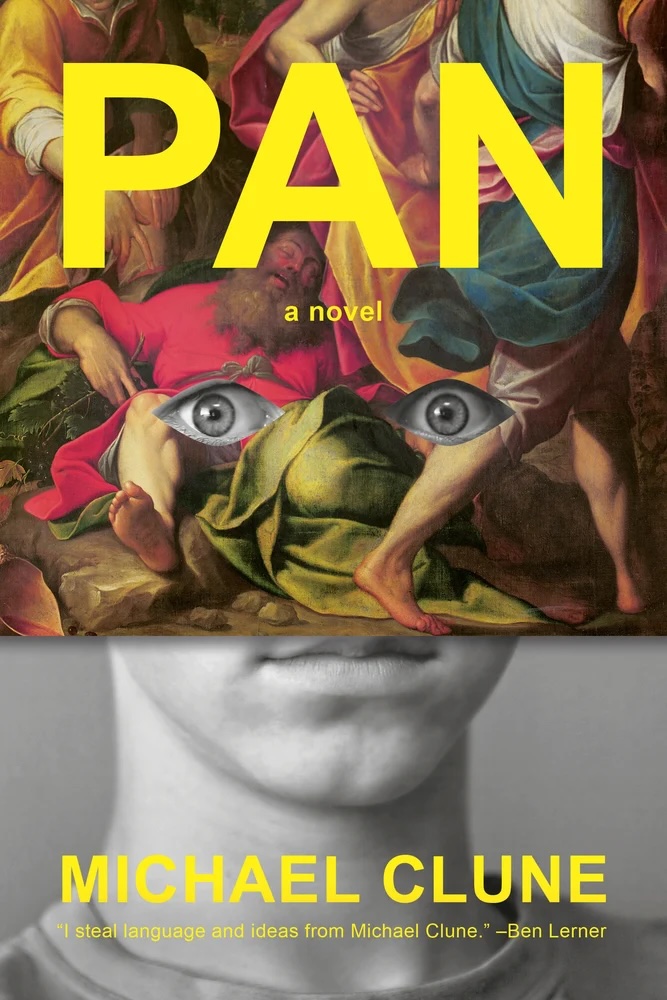

From Pan by Michael Clune. Used with permission of the publisher, Penguin Press. Copyright © 2025 by Michael Clune.