Our Father Issues: A Reading List of Spiritual Disillusionment

Christiana Spens Recommends Patti Smith, Lily Dunn, and More

When I was twelve, I nearly converted to Catholicism. At the time, I was convinced that I wanted to be pure, or rather, light—my father had just been diagnosed with Stage Four cancer for a second time, and I was overwhelmed by the turbulent, passionate and messy adult life that seemed to be edging ever closer, unraveling whatever control I thought I had over myself. And, quite simply, in the presbyterian old town of St. Andrews, famous for the ruins of a cathedral burned down by Protestants centuries earlier, I craved all the incense and color and iconography of the Catholic Church, instead.

I craved sensuality and elation, a kind of bliss, a sort of heaven. I had been to Catholic school for a little while, and found it comforting to know that if you sinned you could still be forgiven, that if you died and begged Jesus hard enough, if you said enough Hail Marys, you could still be loved—you could still transcend your previous transgressions, or those of other people. That in this cold and brutal world, with death and sin so close and so impossible to resist, some kind of light was enshrined in this little building, in this little Church, on the edge of a cliff.

All these reasons to become a fresh new Catholic were true enough, but as I began to realize, as I became a little more honest with myself, the real motivating reason that I decided to start going to Mass was a boy—an Altar Boy, no less! And as I then sat there, every Sunday, with his family, who had taken a shine to me—it occurred to me I was being a little complicated—quite sacrilegious, really—to be combining sin and redemption so closely from the offset.

It gave me something to pray about, at least—an actual sin to confess. I felt guiltily at home in this knowledge. And yet, God was in no rush to absolve me of the sins that I was also in no great rush to let go of. Eventually, I realized the importance of being honest—and this meant, for me, no longer going to Mass. As my Catholicism lapsed, I started reading Camus; my ballet lessons clashed with the conversion lessons. My faith did not exactly fade, but I focused it elsewhere.

*

Patti Smith, Just Kids

I kept reading, and ever since that time, stories of the sacred and the profane fascinated me. I read Just Kids by Patti Smith, and cried several times throughout, realizing my own flawed reality in Patti’s spiritual and romantic tribulations, as well as her great love Robert Mapplethorpe’s. I saw how my own love of iconography and the Saints was so closely entwined with my love and need—and worship—of art. No wonder I had never been a protestant!

I had sat on those hard bare benches, with the droning sermons of doom, and from the youngest age I had wanted to flee; I had felt very strongly about this. Art and the prettier religion—the drama of the faith and the glory—the sin and the redemption, had felt very much the fabric of my own character, and to read about it in the story of Robert Mapplethorpe, through the loving gaze of Patti Smith, set my heart alight and broke it at once. Her music, too, and his photography, went on to structure and decorate this new church—Art—that I never had to doubt I could be faithful to.

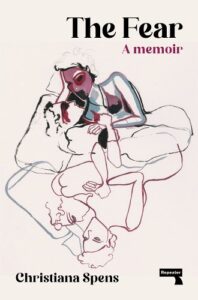

Lily Dunn, Sins of My Father

More recently, as I wrote my book, The Fear—about my own existential crises over the years, triggered by my father’s illness and death, amongst other things—I found new memoirs that resonated deeply, and at times saved me. These books all combined philosophical and psychological inquiry with autobiography, and in particular the complex area of looking for salvation and sense in religion and philosophy, and often becoming disillusioned somewhere in this process.

In particular, I found it fascinating how interconnected spirituality, religion and love were. In Lily Dunn’s Sins of My Father, the author writes beautifully about her journey to come to terms with her father’s disappearance into a cult, during her childhood, and how it affected her adult relationships and search for peace and closure. In Ali Millar’s The Last Days, meanwhile, the author writes about her own mother’s decision to join the Jehovah’s Witnesses when she was very young, how that upbringing traumatized her, and how through immense personal resolution she broke free from a life of complex abuse and its internalization in herself.

Ali Millar, The Last Days

I began thinking more about religion and faith in relation to childhood, and especially the influence of fathers, or their absence, and how so often patriarchal power structures shape religious organizations and people’s experiences of them. I thought more about the demand to obey, especially when I read Millar’s book—and how this simple, repeated demand, or set of demands, shapes people as they grow up and come of age. My own upbringing was complicated, and while I looked to the church, in those early years, to escape my family and the pain I felt at its precarity, I did so because it offered a sort of new family, a refuge, a Father that would never really die.

Though I realized young enough that my need for a church was emotional, fundamentally, I have never stopped thinking about faith, family and love—and their complex interactions. I never stopped wanting salvation from one or the other. I rarely stopped grieving their dissolution.

Matt Rowland Hill, Original Sins

When I had broken up with my first love at university, the betrayal and disillusionment was so crushing that it felt I had lost my religion; it felt that Earth-shattering. More recently, echoes of that feeling returned, reminding me of that sense of total loss and desolation.

And then I picked up Original Sins by Matt Rowland Hill—about the author’s loss of faith and then addiction after a childhood in a fundamentalist family—and found in it a kind of lifeline. When we are brought up in controlling, precarious, chaotic situations, whether it is in a cult, or through being left for one, or in some other way, we have to deal with this crushing loss of faith and love, from the youngest age, before we are remotely equipped to deal with it.

What are the repercussions of this sort of childhood, this philosophical and emotional framework—and how, as individuals, do we find ways to rebuild our lives with true freedom? In these memoirs, each author found reading, or writing, or love, or some combination; the key was in painstakingly creating a new faith and everyday stability despite the ever-present absence of the one we were brought up to want for.

When I read first bell hooks’ All About Love, and then Audre Lorde’s The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, my own ideas about freedom and self-determination transformed. I identified with both authors’ disillusionment with accepted, skewed ideas of love and relationships, and their desires to move beyond this frustration with these patterns and the structures that enabled such oppression and pain to persist.

Both works inspired me to imagine a different way of loving, a different sort of family, a new sort of life and with that, a fresh faith in it. I never really lost my faith, but the structures and articulations of it shifted as I grew up and learnt more. But I will say that these writers and many others all paved the way for this, and that therefore I think of writers, or at least their books, as a free-forming, informal sort of religion. I know, at least, that they saved me, and made me a better person, that writing also saved me—and that seems a good enough religion for me.

___________________________

The Fear by Christiana Spens is available from Repeater, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Christiana Spens

Christiana Spens is the author of The Fear (2023), The Portrayal and Punishment of Terrorists in Western Media: Playing the Villain (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) and Shooting Hipsters (Repeater, 2016). She holds a PhD in International Relations from the University of St. Andrews, and before that read Philosophy at Cambridge. Her writing and artwork has appeared in various publications including The Irish Times, Prospect, Glamour, Stylist, Dazed, the Quietus, The London Magazine, NYRB, and Studio International. She lives in London.