Our Family Secret Was Embedded in My Writing Before I Knew the Truth

Dani Shapiro on Revisiting Her Book on Craft a Decade On

It’s rare and unnerving for a writer to revisit her own work after a long time away from it. The self who wrote the story has been subject to revision. Old ideas have been replaced by new ones, interests and priorities have shifted, dreams have been both realized and dashed. Life has happened.

More than a decade has passed since I wrote my book. My middle-schooler is a college graduate. My in-laws both died in the same year. My husband was diagnosed with cancer and underwent grueling treatment and surgery. A global pandemic and societal reckoning with inequity upended the world as we knew it. These events changed and shaped me.

As I often tell my students, as writers, we are our own instruments. The sum total of our experiences forms the landscape of our imagination and our memory. No matter how experimental or inventive or dystopian or autobiographical or metafictional or fantastical our work might be, we begin with a lens that is ours and only ours; what we glimpse through that lens becomes our thematic material, our subject matter, the fertile ground for our own singular voice.

I was like an arctic explorer, chipping away at the blindingly shiny surfaces of my own family history, searching for something I intuited but could not grasp.

The more intimate our relationship with our lens, the greater our ability to focus in, to whittle and hone the stories we tell. For writers—for anyone making something out of nothing, really—this is the work of a lifetime. At times, we become aware that the lens had been smudged. Or cracked. Clarity is our aim: clarity of thought, of instinct, of heart. A great piece of Buddhist wisdom is that, when it comes to dharma—a life’s calling—if you’re off by a centimeter, you might as well be off by a mile.

If you had asked me, a decade ago, that question all writers are asked and most of us dread—what do you write about?—I would have answered that I write about the complexities of family, and the corrosive power of secrets. From the time I scribbled short stories alone in my childhood bedroom until the time I became a published novelist and memoirist, I wrote about identity and how family shapes it.

Over the years, I began to formulate a personal philosophy as to why these were my subjects. This book is full of that philosophy. I was an only child. I had older parents. Each of them had been through hardships long before I was born. They were tight lipped about the sources of their pain, as are many parents, but there seemed to be a deeper mystery surrounding mine. I wanted to know, to understand. I strained to hear their whispers behind closed doors. I wrote through it, not knowing, until recently, the extent of those mysteries and secrets. Those passages, with knowledge and hindsight, now take my breath away.

Secrets floated through our home like dust motes in the air.

What was I hoping to find? A clue. A reason.

Even in writing expressly about the creative process, I was like an arctic explorer, chipping away at the blindingly shiny surfaces of my own family history, searching for something I intuited but could not grasp.

I was off by a centimeter. And that centimeter formed an entire body of work—five novels and three memoirs. In the last decade, I’ve come to realize that we writers are all off by a centimeter. The process of writing itself is what closes that tiny gap. The obsession with getting it right is why we sit down at our desks each day. In fact, that disquiet, that discomfort, is precisely where our deepest material is buried, waiting to be unearthed.

As I wrote about parents, children, secrets, identity, and otherness, I had an almost physical sense that something was at my back, pushing me. It had no voice; there was no language to it. Rather, it felt like an imperative. If I had to put it into words (which I guess I now do) it felt as if there were a shadow story, and if only I kept at it, I would be able to follow the line of words as they formed a crooked path toward a place where it would all make sense. Where I would make sense.

It was quite by accident and through no great intuition or gumshoe detective work that I discovered, in the spring of 2016—three or four years after I had written my book on craft—that my late, beloved father—he who I sought to unravel and understand more than any other—was not, in fact, my biological father. A secret had been kept from me all my life. I hadn’t suspected. I hadn’t considered it. Never once did I privately turn the possibility over in my mind.

I feel a great tenderness for the younger woman who was struggling to make sense of herself and the world around her.

And yet the proof is on the page. From those first early stories, through each novel, and then the surprising turn to memoir, what is clearly legible, there in black and white, captured in a shelf full of books, is the deepest kind of knowledge. I knew in my sinew and bone. As Carl Jung once wrote, “Until we make the unconscious conscious, it will direct our lives, and we will call it fate.”

Writing is an act of discovery. We aren’t supposed to know what we’re doing when we first set out, when we’re laying down the fragile, terrifying first sentences that may lead to something great, or at least good, or to nothing at all. We’re not meant to know precisely what drives us, because if we possess that knowledge, why on earth do it? What would be the point of all those solitary hours spent sitting alone in a room, out of step with the rest of humanity, if we were simply coloring by numbers, like a bore at a cocktail party telling a story he’s obviously told by rote, hundreds of times before?

When I first made my discovery about my father, I wondered if this meant that all my previous books would now be somehow nullified by the fact that I had been so wrong, so blind, so misguided in my personal philosophy. But instead, quite the opposite happened.

I feel a great tenderness for the younger woman who was struggling to make sense of herself and the world around her. That sense-making formed a body of work. When I re-read the oeuvres of my favorite writers, from Virginia Woolf to Toni Morrison, I am able to trace their journeys, their own sense-making in book after book. This is what we do, whether we are poets, novelists, memoirists, journalists—hell, if we aren’t writers at all, this is still what we do. It’s the human imperative, this piecing together of a life. And so, word by word, we lay down our tracks.

It doesn’t matter if we’re getting it right. In fact, let’s just agree that getting it right is not the goal. Or perhaps we might even go so far as to say that getting it right does not exist. The dignity and nobility of practice, of the very attempt itself, allows for the possibility that one day we will deepen our understanding of what it is to be alive, here and now. Perhaps we will even make something beautiful and meaningful out of all that we don’t yet know.

So consider this your permission to get it wrong, to fail, to learn, to grow as a human and as an artist. Hurl your self at the page each day with this in mind. You will get banged up, sure, perhaps even bloodied. I’m right there with you. And I promise that there is a world full of pleasures alongside those perils. And we will get there, so long as we’re still writing.

__________________________________

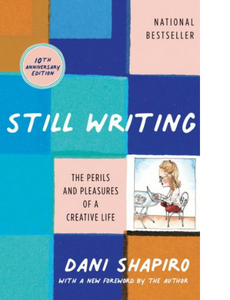

From Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life (10th Anniversary Edition). Reprinted by arrangement with Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2023 by Dani Shapiro.

Dani Shapiro

Dani Shapiro is the author of eleven books, and the host and creator of the hit podcast Family Secrets. Her most recent novel, Signal Fires, was named a best book of 2022 by Time Magazine, Washington Post, Amazon, and others, and is a national bestseller. Her most recent memoir, Inheritance, was an instant New York Times Bestseller, and named a best book of 2019 by Elle, Vanity Fair, Wired, and Real Simple. Dani’s work has been published in fourteen languages and she’s currently developing Signal Fires for its television adaptation. Dani’s book on the process and craft of writing, Still Writing, is being reissued on the occasion of its tenth anniversary in 2023. She occasionally teaches workshops and retreats, and is the co-founder of the Sirenland Writers Conference in Positano, Italy.