The reader was reading an e-book in a café. Whenever he arrived at a sentence that other readers had highlighted, a pop-up notification would display how many times it had been underlined. The reader had come to dread this feature. No matter what genre of novel he was reading, the same type of sentence was always underlined: maxims about love. If a sentence began Love was… or Being in love meant…, it was sure to have a dotted line running underneath, with the notification 650 other readers have highlighted this passage. Meanwhile the rest of the novel would remain unmarked. Pages of precise description, dinner-party set pieces, digressions—the kind of language that he would have underlined with his own pen, if he were reading a physical copy—would go ignored, as though they had made no impression on these other readers at all. Today’s novel was no exception. He clicked ahead, skimming the highlighted passages: The secret of love…; That was what being in love was. Apparently the only language that other readers loved, the reader was coming to realize, was language about love. He could not understand this. He could not imagine what was going on inside these other readers’ minds, while they read. Whenever he came across a precise description—of someone’s thoughts, of a field, of a dinner party—a little pleasure would light up in his brain, yet when these other readers came across that same language, he supposed, their brains must remain blank, their minds as inert and slate-gray as the e-reader’s screen. The boredom he felt when reading maxims about love must be what they felt when reading about thoughts. The pleasure he felt when encountering a sentence with a thought tag in it (he thought; I imagined, it dawned on her) must be what they felt when encountering copular propositions about love (Love was…; Being in love is…). It was hard to fathom, but the evidence of the highlights was undeniable. In the beginning, when he had first bought the e-reader, he had felt superior to these other readers. More sophisticated. They must lack the taste, he told himself, or the judgment, to appreciate the sentences that he did. Or else, he found himself thinking, they must have highlighted their own sentences mindlessly, at the prompting of the pop-up, for no other reason than that the passage had already been highlighted by so many previous readers: as though each reader were like a walker following the same shortcut through a field, he imagined, flattening it further and contributing to the desire line that would go on calling to future walkers. He no longer felt this way about the highlights. By now he had read enough e-books, and encountered enough underlinings, that he had begun to suspect that his was the mind that was missing something. Tens of thousands of readers had been moved by these maxims about love—so moved that they had placed their fingertips or their styluses to the touch screens of their devices and had physically caressed the sentences—and these same tens of thousands of readers had meanwhile passed over precise descriptions of thoughts and landscapes with perfect indifference, numb to their pleasures. What the e-reader had revealed to the reader was just how far he was outnumbered by this numbness. To these other readers, he knew, his mind would be the curiosity. Why did he care more about landscapes than love? What was wrong with him? All his life, if someone had asked him why he read, the reader would have answered that he was curious about other minds. He read to learn how other minds saw, thought, experienced the world. He believed that his own mind could be reflected and enlarged by the language of other minds. Even if he found a book boring, it was enough to remind himself that another mind had produced this boredom—that another brain perceived the world in this boring way—to revive his interest and inspire him to finish. But ever since discovering the highlight feature, he was not so sure he wanted to learn any more about other minds. Increasingly the thought of other minds disquieted him. When six hundred readers highlighted a sentence about love, or ignored a precise description, that certainly gave him an insight into their minds. But it was not an insight that he desired, if anything he felt isolated inside it, locked in a loneliness indistinguishable from solipsism. The idea that he was the only reader in the world underlining precise descriptions frightened him. It would be like attending a dinner party, he imagined, where you were the only guest to order dessert, and where you noticed all your friends wincing one by one as you brought a spoonful of ice cream to your mouth, and where gradually it dawned on you that for these people—perhaps people you had known for years, whose inner lives and sensory experience you had always taken it for granted resembled your own—for them ice cream must taste like ash, and where finally, to seal your dread, you would watch on in horror as each of them delicately dipped their spoons into the tables’ cigarette trays and fed on actual ash, sucking from their spoons like hummingbirds at a feeder, to savor the flavor. You might not want to stay at such a dinner party very long. You might not want to learn how else their minds diverged from yours, indeed you might even begin to suspect—not just that they possessed other minds, different minds—but that they did not possess minds (or what you would recognize as a mind) at all. Robot minds, yes, possibly pod-person minds, but not human minds. The reader set his e-reader down and looked up at the café, studying the faces of the other people around him. Many were silently reading their own books, magazines, tablets, phones. Even now, he thought, were they underlining maxims about love? Some of them could be the very same readers who had left highlights in this novel. Some of them could be highlighting the novel right now. Their minds were a mystery to him, and more and more that mystery was beginning to seem menacing, and mutual. He packed his e-reader and gathered his things. He would stop by the bookstore on the way home, he decided, and buy a physical copy of the novel. As he crossed the café, some of the other readers glanced up from their devices and smiled at him, and he wondered for the first time what being read by them might be like. How would these other readers read him? If he were to precisely describe his own thoughts, he thought—if he were to write about his experience as a reader, about how it felt to encounter other minds, and if he were to post it on the e-book store for others to read—would any of these readers recognize themselves in his descriptions? Would they find something in them, in him, worth highlighting? Or would they skim his thoughts with impatience, waiting for what his mind had to tell them about love? He left the café and headed in the direction of the bookstore. His mind would be boring to them, he knew. They might force themselves to read on, even to finish, but there would be nothing there to underline. He did not think his thoughts had much to do with love. Unless, it dawned on him, as he arrived at the bookstore, this was also what love was. He stood outside the entrance, thinking. Unless the secret of love just was this boredom, he thought. A little pleasure lit up in his brain. Excited, he continued past the store and hurried home. Back at his apartment he went straight to his computer and began to type. He would write it down, he decided, and he would see. He would post it on the e-book store and see. Because what if that was what being in love was after all? Learning to look into an other’s mind, even when it was mind-numbing? Even if you would not highlight a single line it was love.

__________________________________

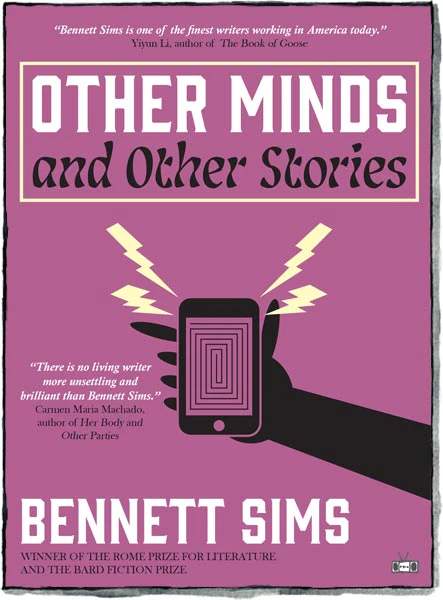

From Other Minds and Other Stories. Used with permission of the publisher, Two Dollar Radio. Copyright 2023 by Bennett Sims.