Orhan Pamuk: Taking Photographs in Istanbul

On Memory, Authenticity, and the Photographer Ara Güler

Translated from the Turkish by Ekin Oklap.

In 1962, my father bought me a camera. My brother had been given one already, two years before. His was like a camera obscura, a black, metallic, perfectly square box, with a lens on one side and a glass screen on the other, on which you could see projected the image inside. When my brother was ready to transfer that murky image onto the film inside the box, he would push on the lever—click!—and as if by magic, a photograph would be taken.

Taking a photograph was always a special occasion. It called for preparation and ceremony. In the first place, film was expensive. It was important to know how many exposures would fit on a roll, and the camera kept a running tally of photographs taken. We spoke of rolls and exposure counts as if we were soldiers in some ragtag army running out of ammunition; we chose our shots carefully, and still wondered whether our photos were any good. Every photograph required a degree of thought and deliberation: “Does this look right?” It was around this time that I began to think about the significance of the photographs I took—and why I took them at all.

We took photographs so as to have something to remember the moment by. As subjects, we faced the camera and posed for others—mostly our friends and families but also our future selves—who would be looking back at this image months and years later. So really, we were having our photographs taken in anticipation of our own gaze back. When we faced the camera, we were “posing” for the future.

Or, in other words, for our future selves who might disapprove of our dishevelment or frown upon our shortcomings. So before taking any pictures, we knew we had better clean ourselves up, make an effort with our clothes, and find something—an interesting view or object, like a car or house—to present as our own in the background. In posing for the future, then, we were also enhancing the present.

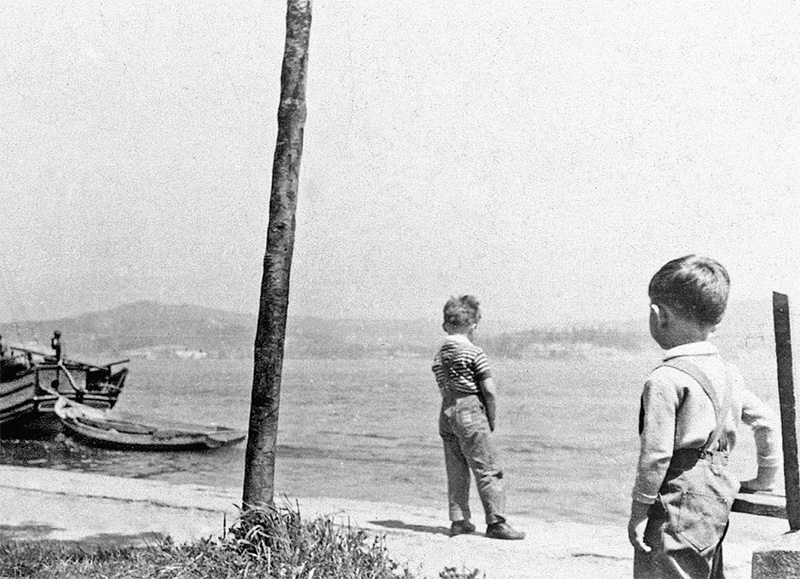

Orhan and his brother. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

Orhan and his brother. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

Our greatest shortcoming, we felt, was never being as modern as we wanted to be. So when posing for the camera, we strove to appear more successful and more modern than we actually were. We didn’t take photographs to document how we went about our daily lives. Quite the opposite: We took and posed for photographs to impress ourselves.

In other words, we had our picture taken to present ourselves to ourselves in a better light. That’s why we took such pains with our appearance before stepping in front of the camera. Religious holidays, birthdays, and other celebrations, when we tended to wear our finest clothes, were particularly convenient times to take photographs. These tended to be happy occasions, or at least ones on which it was not too difficult to pretend to be happy. It was the easiest time to smile for the camera and look good doing so.

In 1949, my father returned from a trip to America with a camera. On this trip, he’d also acquired a fervent belief in the importance of smiling for photographs. If we didn’t feel like smiling, all we had to do was say “cheese” (which we pronounced çiyz and which, we learned, was the English equivalent of what we called peynir), and it would look close enough to genuine smiling. It must have been then that I first began to reflect on the relationship between photography and reality, between representation and authenticity. A photograph supposedly taken to record the truth was in fact no more than a device with which to deceive a pair of eyes in the future.

“The joy of taking photographs must always be at odds with our yearning for authenticity.”

This impression was supported by my father’s efforts to make us look neat and tidy for every picture, the way a schoolteacher would prepare his class for the headmaster’s inspection. Like the camera my brother would receive ten years later, my father’s Rolleiflex was box-shaped and meant to be held at belly height. The delicate lids and flaps around the lens would tinkle pleasantly as my father fiddled around with them. He wouldn’t stare at us directly, but only through a hole in the box, where a mirror reflected our image onto a screen showing the frame as it was about to be recorded.

He would pull out the light meter he carried in his jacket pocket, step toward us and back again, and start adjusting the aperture and the focus of the lens with surgical precision.

Even with his face turned down toward the box, he would still try to maneuver us: “Smile, Orhan; move to the right, Şevket; now all of you, stop fidgeting!” and I’d begin to despair of the photograph’s ever being taken. Sometimes, when we could no longer stand all the contrived solemnity, one of us would stick his fingers up behind his neighbor’s head to furnish him with horns, and soon, despite my father’s admonitions, we would all start prodding and poking one another. Much like the rest of Turkish society, which was self-consciously striving to become more westernized, our family found that our every effort to appear modern and happy seemed to end in frustrating affectedness and hollow ritual. The camera was both a symptom of this problem and one of its triggers.

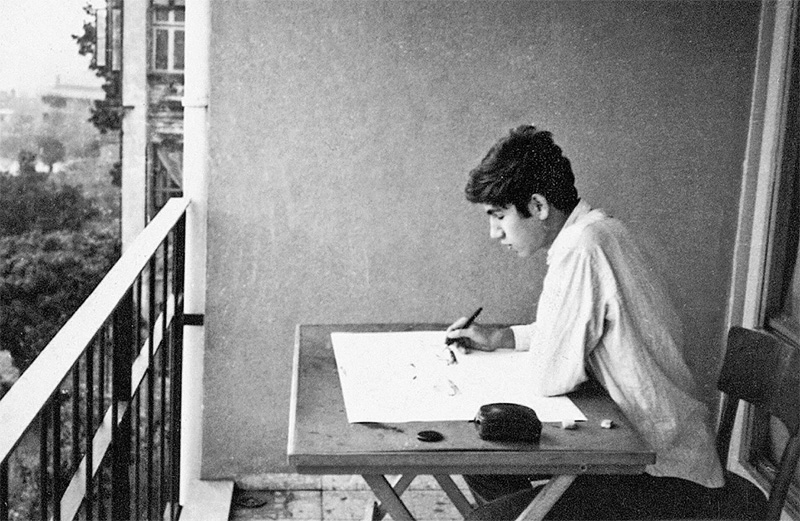

Orhan painting. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

Orhan painting. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

When I finally got my own camera in 1962, I began to imitate all the rituals and conventions of photography as I had learned them from watching my brother and father. But I quickly realized that I lacked my father’s stamina, patience, and determination to rearrange life inside a photo frame. For a start, no one in my family took me seriously or heeded my instructions when I had them pose. I would beg and cajole them to look at the camera or look away, to stay still and stop fidgeting, to please shift a little to the right—but my directions were met only with taunts.

Even after all this hard work, we still had to get our photographs developed at a photo studio before we could actually see them. This too could take quite some time: Once the current roll of film was used up, someone had to drop it off at the studio, and return a week later to collect the prints. Our neighborhood was fairly well-off, with plenty of camera owners, so there was a photo studio with a Kodak sign just three streets up from ours. You could buy and develop film there as well as have your passport photos taken.

Every time I picked up a new batch of photos, I would feel momentarily disoriented. There were often long intervals between visits to the studio, and to be confronted all at once with memories of Bosphorus cruises, birthday parties, and holiday get-togethers that had actually taken place weeks or months apart, always left me with an eerie sense of recurrence. The clothes we wore and the places we posed in may have differed slightly, but the beaming optimism on our faces was always the same. When I compared the prints to the negatives, I discovered that some frames had been left out, perhaps because the image was deemed too blurry, too dark, or too faint. Thus I came to see that the joy of taking photographs must always be at odds with our yearning for authenticity.

Orhan’s grandmother. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

Orhan’s grandmother. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

But there was a graver side to the compound of thrill and unease that I felt when I looked through photos just collected from the studio: All those trips, weddings, parties, and gatherings we had so looked forward to and then relished had already come and gone, belonging now to the past. We were left with our memories, and the erratic record of these photographs. Like our other memories, everything we had experienced, seen, and felt would one day be forgotten. As our elders kept reminding us, we were all going to die someday, “and all that will be left are these photographs.” The only proof of our family life in Istanbul during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, of days spent calling on friends, going on road trips, and dining out, was in these photographs. This truth—of which I was fully aware—was the cause of the distress and anxiety I felt whenever I looked through the prints from the shop with the Kodak sign. Those images presented and preserved for posterity certain aspects of our lives exactly as we would have them be remembered—or close enough. Unfortunately, many other details we had never intended to reveal also occasionally crept in, often in embarrassing forms.

The longevity of a photograph benefits from the divergence between what the photographer or the subjects may have intended to achieve, and the wealth of detail incidentally captured in the image. The qualities that preserve a photograph’s relevance to future generations transcend the purposes of those who saw the frame and captured it. The lens sees things the photographer was never looking at, and years later, new generations, people with fresh eyes and novel interests, will find entirely different meaning in these accidental particulars.

I am fascinated by texts that enrich photographs with secondary and tertiary connotations, contradictions, hints, and implications concealed within details the photographer never “saw.” There is an art to viewing a photograph and describing it with imagination and erudition. When, inspired by a photograph’s collateral subtleties, writers like Roland Barthes and Vladimir Nabokov made poetic observations on the condition of man and on the meaning of memory, they were also teaching literature lovers a new way of looking at photographs, 100 years after photography was invented.

*

By the time I had turned 20, no one in my family was taking souvenir photos anymore. Perhaps this was because the family—no longer a happy one—had long since disbanded; gone were those childhood days when we would pile into the car for a drive along the Bosphorus, and neither did we have much happiness or familial joy left to display.

Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archive.

Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archive.

One day my mother gathered 20 years’ worth of my father’s family portraits she had been storing in drawers, boxes, and in the colored envelopes the photo studio had put them in along with the negatives, and she began to affix them to the heavy, black pages of a vast photo album. She didn’t use all the photographs, but picked out only those she liked and approved of, the ones she deemed to have succeeded at setting the scene. If the moment portrayed was repeated in another image, she would discard the lesser double, and if she saw someone she didn’t like, she’d dutifully trim the photo down until the persona non grata could be expunged from the album. Once she had carefully arranged and affixed a group of photos, she would write an explanatory caption: “Orhan’s first day of school” or “Summer, 1962” or “November 1964: Bosphorus trip!” In a way, my mother’s album was like a diplomatic whitewash of our lives. In the photographs she chose, there were no traces of my fights with my brother, of our parents’ arguments, of any inner turmoil, weariness, regret, debt, financial worry, or anger.

When I began collecting old objects, photographs, and documents for The Museum of Innocence, I noticed that untold albums of other upper middle-class families similar to the one my mother had compiled seemed to have ended up in junk shops, flea markets, and second-hand bookshops. In these albums too I found little that showed these other families in their natural state and daily existence, but instead in an air of formality and a determination to appear proper and modern.

“Notions of beauty or of the landscape of a city are inevitably intertwined with our memories.”

Until the photographer Ara Güler—whose photographs of the city in the 20th century remain unsurpassed—began taking photos of daily life in Istanbul in the 1950s, capturing the city as it woke up in the morning, its convenience stores, its shopkeepers, bus drivers, street vendors, and fishermen, it was rare for the human side of the place to creep into any photographs. The photographs of the so-called Abdülhamit Archives illustrate this point perfectly. Abdülhamit II ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1876 to 1909 without ever leaving his residence, the Yıldız Palace, and from the 1880s onward, he commissioned thousands of photographs of Istanbul and of the Empire, partly to satisfy his own curiosity, and partly for propaganda purposes, to document the results of his attempts at modernization. I love these photographs, devoid of human figures, in which all the streets, government buildings, hospitals, military garrisons, schools, bridges, and clock towers seem perfectly aligned and facing in exactly the same direction, so that everything looks tidier, cleaner, and more modern than it is—just as in my mother’s album. I like to think that I have discovered in these strange photographs a range of emotions that neither the photographer nor Abdülhamit II ever intended to record.

For many years after 1973, at a time when my dreams of coming a painter and an architect were ending, I stopped taking photographs. This choice was dictated by my decision to become a novelist—that is, to observe, describe, and reinvent the universe through words rather than visual images.

A view of the Bosphorus. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

A view of the Bosphorus. Photo via Orhan Pamuk’s archives.

As far back as the 1960s, while still a young boy, I already knew of Ara Güler the famous photographer. I would hear stories about him all the time, for his photographs appeared in the weekly Hayat, whose editor and chief columnist was married too my maternal aunt. But Ara Güler wasn’t just the photographer of Istanbul and the whole of Turkey; he had also made extraordinary portraits of some of the 20th century’s most brilliant creative minds, from Picasso to Hitchcock. When he came to my home for the first time in the summer of 1994 to photograph me for the cover of the book supplement of the newspaper Dünya, I was 42 years old. That was the day I said to myself: “Now I have really become a writer.” Having my photograph taken by Ara Güler made me feel that I had been accepted as a writer, that I had earned a place in history, and that I would not be forgotten.

Much as with all the most generous and complex works of art we enjoy, it is hard to put one’s finger on the secret of Ara Güler’s photographs, to say what exactly makes them so beautiful. (Like many contemporary photographers, Ara Güler likes to insist that photography is not an art.) His family home, the place where he spends most of his life, a stone’s throw from Galatasaray Square, serves as the de facto Ara Güler archive, and indeed feels to me like a sort of archival paradise, one that I visit as often as I can to browse through photographs of old Istanbul. (I hope that one day this building in the heart of the city may become an Ara Güler museum and official archive.) Looking at Ara Güler’s photographs of the city, its streets, and its views, I notice that the basic emotions they evoke—such as melancholy, weariness, insignificance, humility—are often also present in the expressions of the people in the foreground. Ara Güler still tells me sometimes: “You only like my photographs because they remind you of your childhood.” I respond that I like his photographs because they are beautiful. We end up discussing the relationship between beauty and memory. Notions of beauty or of the landscape of a city are inevitably intertwined with our memories.

__________________________________

From the introduction to Istanbul: Memories and the City (Deluxe Edition). Used with permission of Knopf. Copyright © 2017 by Orhan Pamuk.

Orhan Pamuk

Orhan Pamuk won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006. His novel My Name is Red won the 2003 IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. His work has been translated into more than 60 languages.