Oprah’s Book Club and... Dying? How Do Writers Get Famous

Cass R. Sunstein Considers the Factors and Trends That Lead to Literary Recognition

Why are some authors and books iconic? Why do other authors and books tank? It’s tempting to say that William Shakespeare is uniquely talented, and so is Stephen King. But, of course, there are plenty of amazing writers out there that you haven’t heard of them.

Benjamin Franklin had a sister, named Jane, who was extraordinarily talented, but who never got a chance to cultivate her talents. She wrote these words to her brother: “Thousands of Boyles Clarks and Newtons have Probably been lost to the world, and lived and died in Ignorance and meanness, merely for want of being Placed in favourable Situations, and Injoying Proper Advantages.” Those are poignant words; Jane Franklin might have been speaking of herself.

We should understand “favourable Situations” and “Proper Advantages” very broadly. In her lifetime, Jane Austen wasn’t such a big deal. Long after her death, she benefited from a host of twists and turns, otherwise known as Proper Advantages, including clever, tireless work by her family members (perhaps above all her nephew, James Austen-Leigh).

For poets, novelists, musicians, actors, and others, talent is not enough.

For poets, novelists, musicians, actors, and others, talent is not enough. Social influences of one or another kind are crucial. In extreme cases, someone needs to start a kind of mania, or something close to it, and then watch the dominos fall. Successful writers usually depend on some kind of lightning strike. Ecclesiastes gets it right: “The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favor to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.”

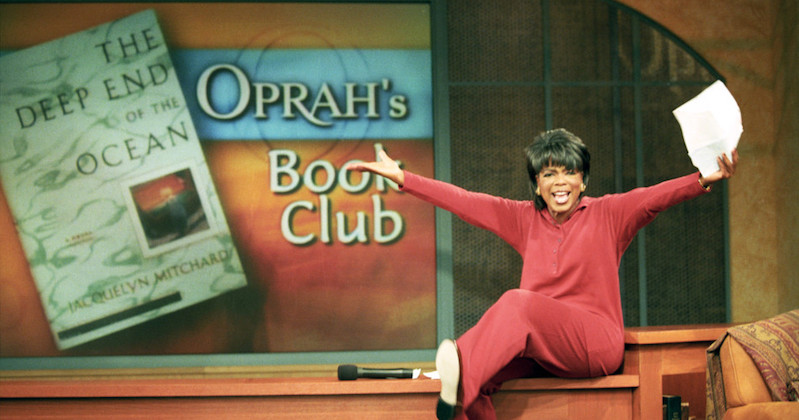

All this is a bit abstract. For a vivid illustration, consider Oprah Winfrey’s Book Club, which initially ran from September 1996 to April 2002. You may recall that in that period, Winfrey was extraordinarily famous, with a TV talk show that was watched by millions of viewers. She was also trusted and admired. During the relevant period, she made forty-eight book recommendations.

Here is the question: What was the impact of being selected by Oprah? You might speculate that it would be pretty large in the short-run, but not in the long-run. Or you might think that she could give a book a little boost for a day or two, or maybe even a week, but not for much longer than that. Even Oprah Winfrey could not work miracles. Maybe quality would ultimately prevail, and books would return to the place they would otherwise be, no matter what Winfrey recommended.

Richard Butler, Benjamin Cowan, and Sebastian Nilsson have investigated the impact of being selected by Oprah. Their conclusion is signaled by their title: “From Obscurity to Bestseller.” The central finding is that not one of the forty-eight books was in the top 150 bestsellers in the United States in the week before Winfrey recommended them—but that every one of them made the list in the week after!

Winfrey’s picks made that list not for a very short period, but for at least three months. More dramatically, the strong majority of Oprah’s selections had never been on that list before, and the highest ranking that any of them had achieved was 25. Still, every one of Oprah’s first eleven selections made it at least into the top four.

You might well speculate that those selections would surely do less well than the average bestseller. If so, your speculation would be reasonable—but wrong. Her selections stayed on the bestseller list at least as long as and perhaps a bit longer than other bestsellers. Indeed, several of her selections had multiple runs as bestsellers, and fourteen of them ended up in the top 150 as paperbacks. It is worth underlining that finding. On average, the fourteen paperbacks became bestsellers forty-two weeks after Oprah picked them.

The basic point is that if Winfrey endorsed a book, it was guaranteed to become a bestseller, and then to enjoy strong sales for months. For retail bookstores, an Oprah pick produced about $80 million in new sales. Why did that happen? Consider four reasons:

1. She had a great deal of credibility in her audience, which trusted what she had to say.

2. Because her endorsement was known to drive sales, it produced an immediate “network effect”: People wanted to be part of the network of readers of Oprah’s pick.

3. Booksellers themselves knew what was coming, and put her picks on display.

4. People thought that it would be an excellent idea to read one of her picks, so as not to be left out.

Oprah Winfrey was (and is) unique, of course, but these are not meant only (or mostly) as points about how her picks fared. Pre-Oprah Oprahs, of various sorts, are responsible for the fame of some of the greatest literary figures in the English language, including not only Jane Austen but also John Keats, William Blake, and Herman Melville.

That points to a possibility or perhaps an inspiration. Lost Einsteins, or lost Shakespeares and Miltons, might be found again. In fact they are being found every day. They are being found in the same way that so many others have been found again. And if we can stay alert to the fact of their existence among us, right now, many fewer will get lost in the first place.

But here’s another question: Do you think that writers, artists, and musicians will sell more of their work in the period immediately after they die? Is death good for business?

A possible answer is: definitely not. People either do or do not like the Beatles, Frank Sinatra, Picasso, John Updike, and Janis Joplin, and whether they buy books, paintings, or music will depend on whether they expect to like the work, not on whether the person responsible for them is living and in good health. Whether a writer has died should be a matter of indifference—just as it is a matter of indifference whether a writer is married or single, or young or old, rich or poor. The work is what matters.

As it turns out, this reasonable answer appears to be wrong. We don’t know exactly why, but death does appear to be good for business. As Gore Vidal said when told of the death of Truman Capote, “a wise career move.” Vidal was onto something.

Lost Einsteins, or lost Shakespeares and Miltons, might be found again. In fact they are being found every day.

The most careful work comes from Italy, where the economists Michela Ponzo and Vincenzo Scoppa studied the effects of a writer’s death on book sales. The central finding is that in the period after an author dies, the probability that he or she will be on the bestseller list leaps dramatically. Indeed, it increases by more than 100 percent!

Ponzo and Scoppa also find if you want to make the bestseller list, you are a lot better off dying young. Writers who died at or under the age of 65 enjoy a significantly bigger “death bonus” than do writers who died over that age. In addition, media attention makes a big difference. For book sales, the beneficial effect of death is concentrated in writers whose death is on the front page and is otherwise covered prominently and often. Broadly similar findings have been made for artists: the price of their paintings increases after death, and the effect has been found to be larger for artists who die young.

These findings raise many questions. Let’s fuss a bit. If you took the full universe of writers in the world, and ask whether their sales jumped after their death, the answer is overwhelmingly likely to be a firm no. There are approximately a zillion writers in the world right now, and the number of people who actually publish a book in any given year is probably in the vicinity of four million. (That is the annual number of books, and while some authors publish more than one per year—I plead guilty as charged—four million annual authors is unlikely to be far off.) If we estimate that about nine of one thousand people die every year, we might estimate that very roughly, thirty-six thousand of those four million published authors will die annually.

How many of them enjoy a big boost in sales? Undoubtedly very few! Most writers don’t sell many books at any time, and the year after their death isn’t any better than the year before their death. If you are an obscure writer (and most writers are obscure), you should not think that if you die, your books are going to take off.

Ponzo and Scoppa limited their research to writers who had at least one book on the bestseller list, and they used a set of ingenious strategies to test whether writers become more likely to end up on the list six months after their death. All this means that we have to say that if we focus only on writers with a certain level of renown, sales might well increase after death, at least if their death receives serious newspaper attention.

That’s an important finding. What’s behind it? The simplest explanation points to attention. When well-known authors die, people focus on them. You might not think about Joyce Carol Oates or Mick Jagger very much, but if either dies (and here’s a hope that neither ever does), a lot of people will suddenly think about them a fair bit—and go right out and buy their work. In a way, death is like a well-financed publicity campaign, or like being chosen by Oprah Winfrey, and it can work for the same reason. Death can also create an instant network effect: people might think that other people are going to be reading or listening to the deceased, and that they ought to join them.

Emotions undoubtedly matter as well. Many of us feel connected to well-known writers, and death produces a period of grief and mourning. One way to handle those feelings is to spend time with the deceased, and in that way to stay connected with them. If you lose someone you love, you might cherish photographs and letters. Writers and artists might be people you love, or at least to whom you feel attached; they might be part of the fabric of your life. Their work is the equivalent of photographs and letters. You want to linger over them.

__________________________________

From How to Become Famous: Lost Einsteins, Forgotten Superstars, and How the Beatles Came to Be by Cass R. Sunstein. Copyright © 2024. Available from Harvard Business Review Press.

Cass R. Sunstein

Cass R. Sunstein is the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard Law School, where he is the founder and director of the Program on Behavioral Economics and Public Policy. He is by far the most cited law professor in the United States. From 2009 to 2012 he served in the Obama administration as Administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. He has testified before congressional committees, appeared on national television and radio shows, been involved in constitution-making and law reform activities in a number of nations, and written many articles and books, including Simpler: The Future of Government and Wiser: Getting Beyond Groupthink to Make Groups Smarter.