One Way to Write About a Millennial Protagonist? Don't Settle on a Single Form.

Emma Jane Unsworth on Writing a Multi-Format Novel

Let me start by saying this: I didn’t want to write a “digital book”—and by that I mean a book utilizing online modes of communication—for various reasons. Firstly, it would date quickly. Given that it takes the great lizard of literature a year to turn around a novel from final draft to publication, and social media changes approximately every 0.5 seconds, it would be old before it was published. Crucial drama points would become irrelevant, such as seeing how many likes a post gets on Instagram, for example—which actually did change in the UK in the time between writing and publication.

Also, and it pains me to say it, I’m a snob. But there comes a time when you have to batten down your inner snob, and accept the writer you really are, and the story you have to tell. The story I had to tell was about a young woman whose life was in tailspin. Betrayed by her body, her man and her better instincts, she had become a traumatized, needy failure. A ghost in her own home. Lonely, broken, at night, there was only one place she was going to go. Online.

An online existence is not such a stretch for a contemporary character. This is how most of us are communicating these days: Twitter, Instagram, email, texts. In fact, I find it almost jarring when a novel doesn’t include at least some mention of the characters using the internet. And, of course, epistolary novels are nothing new. From Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa and Pamela, to Jane Austen’s letters, this method of storytelling goes back as far as novels themselves.

More recently, some of my favorite reads have used epistolary techniques to powerful effect. I especially enjoyed Where’d You Go, Bernadette? by Maria Semple, which deploys emails, memos and various other found paraphernalia in a lively way, with real heft of heart.

The messages we pause over, delete, or write just to feel better. Didn’t they have a meaningful place?

Do you know what the best thing was about writing fictional texts and emails? It was fun. I galloped through those sections, mixing up the online communications with straight narrative when I needed to slow things down or do something in the past. The quickfire back-and-forths were the most pleasurable (and cathartically painful) sections to write.

I noticed something else, too. Technology offered some excruciating comedy pratfalls: Delete, CC, Drafts, and the most dreaded: Reply All. A letter getting into the wrong hands can take days, even weeks, to pay off dramatically. But you know when you’ve sent a message to the wrong number. And that particular modern hell, as immediate as it is soul-filleting, is a great tool for the novelist.

I also found great scope in the Drafts folder within my protagonist’s Inbox. She could write emails that she never intended to send, showing how at odds her real feelings were with what she expressed to the world. The messages we pause over, delete, or write just to feel better. Didn’t they have a meaningful place? Didn’t they somehow say more about a character than the messages they actually released into the world?

After all, the things we don’t send, like the things we don’t say, are often the most telling. Seeing the unseen can be a great thrill of a novel. These drafts would be like diary entries, but addressed to people with whom she had encounters. Dissatisfactory encounters, usually.

Ridiculousness also became a big part of my book. My main character is a self-obsessed idiot. Sure, she’s traumatized, but I don’t want that to excuse her completely. She’s an ass. I love her, in the way I love Larry David on Curb Your Enthusiasm or Ignatius J. Reilly in A Confederacy of Dunces, but she worries too much about what other people think of her. She is in this way a product of her world. I love and I hate my protagonist in the way I love and I hate the internet.

I pushed her as far as I could to show the parameters, to control my fears, if you like. In this way, it’s a satire. But female characters, and female authors, are rarely allowed to thrust ourselves into the realm of satire. It’s too wild a place for a woman. So part of the challenge of writing my protagonist was balancing what I thought the reader could endure of this Massive British Ass with what I wanted to do in terms of making her believable, complicated, and a real human being with a story to tell and a journey to go on—in a digital world I wanted to critique.

By engineering a process of transparency—by giving the reader all of her, indeed much more than she had of herself—I could create just enough sympathy to carry the novel through. I’m not bothered about making characters likeable. I believe in the existence of difficult women—and not just the ennobled difficult ones. The unbearable, irredeemable difficult ones, too.

I wanted to show my narrator’s brain exploding on the page.

But I do, ideally, want readers to finish my books. Someone once said to me: I like your writing, but the women in your stories are so awful I can rarely get beyond Page 5. Which is the literary equivalent of the dentist saying: Your teeth are fine, but your gums are going to have to come out. Ah well, here’s to sucking food through a straw. You can’t please everyone.

What pleases me as a writer is using the page in a playful way. I love books that do this. I’m thinking of the two black pages after Yorick’s death in Tristram Shandy; the masterful use of footnotes and columns in Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts; the apocalyptic tapestry of Max Porter’s Lanny, where words jumble and fight for air. I like self-conscious books. I don’t mind being reminded that I’m reading a book when I’m reading a book.

In Grown Ups, I wanted to show my narrator’s brain exploding on the page. In between the digital interactions, I used single words on pages, single punctuation on pages, blank pages: things falling and flying everywhere. I wanted the book to have a frantic, frenetic energy because that was how my protagonist felt, even though she wasn’t entirely aware of it.

Of course, the novel is a swine to read out loud. Short of wearing different hats, or turning this way and that, or putting on different accents, I discovered that it is well-neigh impossible to convey the sense of a text message conversation during Zoom readings or, earlier in the year, at bookshops. The actress who did the audiobook deserves a medal. But people have been very forgiving. And hopefully on the page, in the quiet internal reading, it works okay. At the very least, I hope it feels real. A hard, funny, sad truth, about a hard, funny, sad woman. Unfiltered.

__________________________________

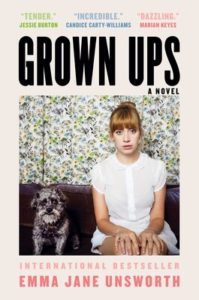

Emma Jane Unsworth’s novel Grown Ups is available now.

Emma Jane Unsworth

Emma Jane Unsworth has written two award-winning novels: Hungry, the Stars and Everything and Animals. She wrote the screenplay of Animals and the film, directed by Sophie Hyde and starring Holliday Grainger and Alia Shawkat, premiered at Sundance 2019 and was released in the UK later that year. She regularly writes essays for newspapers and magazines, including The Guardian Weekend. She also writes for television.