On “White Slavery” and the Roots of the Contemporary Sex Trafficking Panic

Chanelle Gallant and Elene Lam Explore the Racist Roots of a Moral Panic

The “modern slavery” panic isn’t so modern. Its roots go back to nineteenth-century Europe and North America and the “white slavery” panic. Reaching its zenith in the early twentieth century, the white slavery panic was a widespread expression of terror about racialized migration and the movement of poor European women into cities and into sex work. It entailed an international campaign promoting baseless claims that gangs of “foreign-born” men were preying on white virgins of England and America, luring them to the city with false promises of work or marriage, only to make them captives in an underworld of sex slavery.

Here, we’ll look specifically at how the white slavery panic operated in the US and Canada from the late 1800s to the 1930s. During that time, thousands of newspaper reports, magazine articles, pamphlets, theater productions, and sermons, doctors, ministers, politicians, social movement leaders, journalists, and artists whipped up a mass panic by claiming that they had discovered a new type of slavery—forced prostitution committed by migrant Asian, Arab, and Jewish men. With titles like “White Slave in Hell,” and “Social Menace of the Orient,” the stories were highly sensationalized, fictional accounts of the grim horrors that befell white women in the sex industry as a result of the “foreign menace”—Asian and other racialized men. The myth that nonwhite men pose a threat to white women’s sexual purity is perhaps as old as America and core to how the US colonists and enslavers justified white-supremacist domination, colonization, chattel slavery, lynching, and imperial wars. The white slavery panic put the mythology of white purity and racialized sexual danger to work in justifying the subjugation and exclusion of racialized migrants, spreading lies that migrant men were kidnapping innocent white girls and women, trafficking them across international borders, and sexually victimizing them.

Implied in the term white slavery is the idea that only certain (innocent) white women matter, and that nonwhites are their enslavers. White slavery campaigners wanted to protect the innocent white women from the foreign enslaver, but they also wanted to protect white men and the white nation from what they saw as the dangerous foreign woman in the sex industry. Asian sex work was understood within the broader framework of racist ideologies like the “Yellow Peril” that constructed Asian migrants as dangerous, uncivilized, dirty, immoral, permanent outsiders, and bad workers whose presence undermined the building of the US nation—and therefore required surveillance, containment, and exclusion. Sex work was viewed as a contagious “moral disease” that spread through Asian cultures because of their lower level of development and patriarchal subjugation of women.

In reality, white and Asian sex workers faced very diverse circumstances depending on what period in history we look at, their geographic location, their access to rights and resources, and many other factors. Some were better off than their sisters in other forms of work, and used sex work to achieve a kind of economic stability that was otherwise impossible for Asian migrant women. But most of them worked under the same oppressive conditions as other Asian migrant workers, with few rights and protections. They experienced serious problems like exploitation, coercion, and abuse. White sex workers were largely poor and working-class mothers who chose sex work to supplement other work, because of its higher wages. Then, as today, their working lives were not the result of sex slavery, but a rational means for surviving the impoverishment of women and the white supremacist exploitation of racialized labor.

White American suffragettes were heavily implicated in the white slavery scare, stoking racist fears about Asian men to build support for their campaigns for political power and the vote. They presented themselves as angels of salvation who, if given the vote, would put it to good use by fighting Asian immigration and thwarting growing Asian political power. In their 1907 book Heathen Slaves and Christian Rulers, Elizabeth Wheeler Andrew and Katharine C. Bushnell wrote: “We must realize what may happen to American women if almond-eyed citizens, bent on exploiting women for gain, obtain the ballot in advance of educated American women. We must realize how impossible it is to throttle this monster, Oriental Brothel-Slavery. . . . Beside the peril arising directly from the flood of Orientals who are accustomed to dealing with women as chattels, there will be the peril from a debased American manhood.”

White American suffragettes were heavily implicated in the “white slavery” scare, stoking racist fears about Asian men to build support for their campaigns for political power and the vote.

Another white suffragette, Rose Livingston, gave lectures across the US about New York City’s Chinatown, depicting Chinese men as sexual threats to white women and casting herself as the “Angel of Chinatown.” Historians attribute her activism as a contributing factor in the push to get the Chinese Exclusion Act passed. The white slavery panic attracted popular support among white people because it drew on myths that were and remain deeply rooted in white supremacist US culture—the sexual danger of racialized men to white women and the danger of Asian women who tempt and corrupt white men.

Most historical interpretations of the white slavery moral panic focus heavily on how the white ruling class used its false claims about white women’s sexual virtue and racialized “sex slavers” to regulate sexuality and gender. But less has been written about the way the white slavery panic was also about the regulation of race, class, and labor. Its proponents used the white slavery panic to control the labor of Asian migrants and protect white ruling-class wealth and political power.

Following the Civil War, the labor system in the US went through a cataclysmic transformation, in part because of the formal abolition of chattel slavery. Wealthy industrialists and landowners relied on tens of thousands of migrant workers from China, India, and other parts of Asia to replace enslaved workers and to fill roles in a rapidly growing economy. Migrant workers’ conditions were hyper-exploitative, dangerous, and unfree. Many were locked into indentureship contracts and forced to perform years of grueling and dangerous labor. Some Chinese workers were in debt bondage, forced to work for no wages as they paid down debts and whipped if they tried to escape. But over time, migrant Asian workers began to gain some economic independence and community power in North America. They founded community associations, advocated for their political and human rights, built businesses, and started their own families with children who could claim a right to remain in the US. They were an increasing threat to ruling-class white control over land and resources. Meanwhile, the building of the transcontinental railroad had been completed and capitalists’ desire for cheap Asian labor was in decline.

While chattel slavery had been outlawed, many of the institutions created by the slave-owning establishment in the US remained intact or were adjusted so that the white ruling class retained full control of the political and economic systems. The wealthy continued to profit from the extreme exploitation of Black and Asian labor through racist, but legal, labor practices, such as sharecropping, indentureship, and the convict leasing system. And much of the massive, unprecedented accumulation of wealth that white, ruling-class American families had accrued through enslaved Black labor remained in their hands. Chattel slavery had been outlawed, but in many ways, it lived on through structural racism and extreme economic inequality. The white slavery panic offered the white ruling class a means to take control over the meaning of slavery and their perceived relationship to it. By presenting chattel slavery as “over” because it was no longer legal, the white ruling class could indemnify themselves against accountability to formerly enslaved people, their descendants, and the ongoing legacy of slavery. According to them, they had abolished it.

Second, the concept of white slavery allowed the white ruling class to position themselves as the “new victims” of slavery and racialized people as the new enslavers. Chattel slavery was something that white people and white society did to Black people. It involved forcing people to work and often forcing them to move, such as being kidnapped, transported to plantations or sold to faraway enslavers, and separated from their families. The white slavery panic reversed these roles to position white people as the victims. This new form of slavery was characterized as something that racialized people did to white society. Stories of white slavery focused on racialized, migrant men who forced women to work in the sex industry, and the stories often featured some form of forced movement (e.g., white virgins being kidnapped and transported to faraway lands). This granted the white ruling class political cover to attack their alleged perpetrators—migrants and workers—and justify this as self-protection. They used white slavery to justify their campaigns to end Asian migration into the US, and restrict Asian social and political power in the country by claiming this as a necessary form of protection against “foreign enslavers.” The white slavery panic—as part of the broader anti-Asian Yellow Peril panic—led to the first US federal immigration exclusion law based on race: the Page Act of 1875.

The concepts of “white slavery” allowed the white ruling class to position themselves as the “new victims” of slavery and racialized people as the new enslavers.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 is often cited as the first federal immigration ban based on race in the US, but it was preceded by the Page Act, which became law in 1875. US politicians sold it to the public as an anti-trafficking measure, but its main function was to ban Chinese women. In the history of racist immigration policies, the Page Act is largely ignored for the important role it played: it banned unfree indentured labor and formerly incarcerated workers as well as Chinese women who were seen as entering the US “for the purposes of prostitution” or other “lewd” and “immoral purposes.” The act was justified on the basis of the perceived close associations between Chinese sex workers and slavery, corruption, and disease. Chinese women who wished to immigrate were forced to submit a statement affirming they had suitable sexual morals, and to undergo repeated questioning by US officials about whether they had ever engaged in prostitution or lived in a house of prostitution. US border officials were granted total authority to determine who was or was not admissible based on this policy of exclusion. They used it to exclude nearly all Chinese women seeking entry, by rarely enforcing the Page Act’s prohibitions against the entry of forced labor while aggressively enforcing its anti-trafficking/anti-prostitution provision. In early 1882, during the few months immediately preceding the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act, only 136 of the 39,579 Chinese people who entered the United States were women. Thus, years before the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act, the US government had already found a way to restrict Chinese migration into the US—by banning women under the pretext of protecting them from sex slavery. Yet the racist and sexist discrimination of the Page Act is commonly overlooked, perhaps because even today the immigration exclusion of Chinese women is seen as less important than the exclusion of men.

The Page Act claimed to be protect Asian migrants from coercion and exploitation by prohibiting unfree migrant labor and labor that was assumed to be unfree—prostitution. We argue that the real purpose of the Page Act can be seen in its key effects—the de facto ban on Chinese women and the precedent it set for a more explicit ban on Asian migration, through the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Page Act was written by and named after a Republican representative, Horace Page, who had been advocating for years (and failing to get support from the US Congress) to ban Asian people from entering the US. Page and others had been unsuccessful because “corporate interests, trade agreements and treaties with China did not permit the United States to altogether ban Chinese immigration at that time, and race-based immigration exclusion was legally and morally unprecedented. So legislators had to use different tactics to disenfranchise and exclude Chinese immigrants.” The Page Act, as an “anti-trafficking” law, was the tactic that worked. It was only one of hundreds of anti-migrant measures of the time, and it demonstrates how Asian migrant sex workers have been constructed as dangerous bodies, how the state uses anti-trafficking as a cover for racist border policies, and why migration rights are so important to migrant sex worker justice.

The US government also used the white slavery panic to pass the White Slave Traffic Act (also known as the Mann Act) in 1910, which criminalized the movement of women across state lines for the purposes of prostitution or other purposes deemed sexually immoral. It is considered the first US “domestic sex-trafficking” law, and it remains in effect, although the phrase “white slave” has been dropped from the law’s name. The law was enacted in the first year of the Great Migration, when millions of Black people began to move out of the rural South to other parts of the US to escape the Jim Crow segregation laws. Although the police used the White Slave Traffic Act to criminalize many kinds of unsanctioned behavior, they most notoriously used it to criminalize Black mobility across internal US borders, as well as Black people’s work and sexuality. Black people could be charged with white slavery offenses for any movement that was considered suspicious, especially if it involved white women and sex.

_____________________________________________

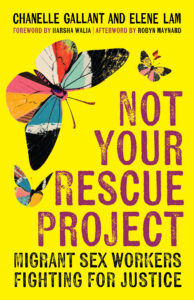

Not Your Rescue Project: Migrant Sex Workers Fighting for Justice by Chanelle Gallant and Elene Lam is published by Haymarket Books and reprinted with permission.

Chanelle Gallant and Elene Lam

Chanelle Gallant is an author, activist, and movement strategist who has worked in the areas of sexuality and criminalization for over two decades. Her writing has appeared in dozens of publications, most recently the New York Times best-seller Pleasure Activism, Beyond Survival, and Defund, Disarm, Dismantle, and her work has been discussed in the Washington Post, the Advocate, Esquire, Vice, and every national media outlet in Canada. Chanelle is on the national board for Showing Up For Racial Justice and has helped to found or support numerous sex worker organizations. She has an MA in sociology and was a Lambda Literary Fellow. Elene Lam is an activist, artist, community organizer, educator, and human rights defender. She has fought for sex worker, migrant, gender, labor, and racial justice for over twenty years. She is the founder of Butterfly (Asian and Migrant Sex Workers Support Network) and the cofounder of Migrant Sex Workers Project. She has used diverse and innovative approaches to advocate social justice for migrant sex workers, such as leadership building and community mobilization. She holds a master’s of law and master’s of social work. She is a PhD candidate at McMaster University (School of Social Work) and is studying the harm of the anti-trafficking movement. She was awarded the Constance E. Hamilton Award for Women’s Equality by the City of Toronto.