On Victorian Paleoart and the Birth of a Sci-Fi Novel

C. E. McGill Considers Frankenstein’s Monster and Gothic Sci-Fi

I remember vividly the day I first encountered Victorian paleoart. It was during a session of HI 482: Darwinism in Science and Society, a fascinating and eclectic class taught by my academic advisor, a brilliant historian of science who knew precisely how to bring the subject to life. Dimming the lights, he loaded up a PowerPoint full of lopsided ichthyosaurs and bat-like pterosaurs, humanity’s earliest attempts at bringing these extinct creatures to life.

Then came the pièce de resistance: The Sea-Dragons As They Lived, by John Martin, an artist most well-known for his epic paintings of historical and Biblical apocalypses. In stark black and white, the piece showed three reptilian creatures locked in vicious combat amidst a stormy sea, sharp-beaked pterosaurs picking at the corpse of another monster dead on the shore. It was so fantastical, so needlessly melodramatic—like something from a ‘50s B-movie—that laughter rippled across the room.

I laughed with them, but even as I did, I was desperately in love.

*

I’ve always adored science fiction. My father raised me on a steady diet of Star Trek and Doctor Who; I devoured my local library’s sci-fi/fantasy section, then the science history section, fat tomes on the history of nuclear fusion, ancient astronomy, the number zero. I applied to university in Aerospace Engineering with a minor in Physics, because that seemed like the fastest way to get to NASA. I knew it would be challenging; I didn’t know, however, that the challenging part would be my seething hatred of group projects, lab reports, and industry networking events.

Two years in, stressed and despondent, I picked up a book—for fun—for the first time in years, and felt like I’d taken a breath of fresh air. I began reading again, writing again, carving out hours late into the night, astonished to find that my teenage writing skills weren’t too rusty after all. Despite my best efforts, it seemed that I was an artist at heart.

Aware that I was already throwing away a bright and financially stable future, I decided that I might as well study what I loved; and what I had loved all along, I realized, was not so much science in isolation but science as a source of inspiration, a symbol of hope—a story. I wanted to understand why the image of scientific discovery presented in fiction (and popular nonfiction) is often so different from the reality, how real science inspires science fiction, and vice versa. I put together a patchwork degree composed of creative writing, history, and literary analysis—and in the process, became re-acquainted with Frankenstein.

*

The nineteenth century was a period of immense and rapid change in Britain, much of it due to the Industrial Revolution and the advancement of scientific knowledge. “Advancement” here is a tricky word, for although many of the scientific findings of the century made people’s lives better—curing diseases, improving sanitation, shortening arduous travel times—they also left countless cottage workers unemployed, were used to justify scientific racism and misogyny, and helped the British Empire exploit its colonies in ever-more efficient and brutal ways.

There is a reason, then, why the book that is widely agreed upon to the be the earliest work of science fiction—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—has a complicated relationship towards science.

As in many Gothic works, nature is presented as a sublime and healing force, in direct opposition to the unnatural and corruptive force of science. But at the same time, Victor’s passion for science at the beginning of the novel is genuinely heart-warming, and his goals are typical of post-Enlightenment rationalism and optimism: if the body is just a complicated machine, then surely by taking it apart and putting it back together, he can cure death.

In this respect, we know that Shelley was inspired by the experiments of Luigi Galvani, the scientist who discovered—when a spark from his scalpel made a frog he was dissecting begin to twitch—that our muscles move using electric impulses. Galvani’s nephew Giovanni Aldini spread these findings far and wide through a series of grisly public experiments upon animal heads and even the corpse of a convicted murderer in 1803.

At the time, in fact, executed murderers were among the few types of bodies one was permitted to use for dissections and demonstrations, a fact which greatly frustrated the country’s medical schools. For many years, there existed in London and Edinburgh a thriving trade in body snatching, leading some people to install “mortsafes,” or large iron cages, over their loved ones’ graves. In much the same way, Victor Frankenstein obtains the corpses he needs by robbing charnel houses, abandoning human decency for the sake of science.

Frankenstein, then—like all good science fiction—is not just a spooky story, but a window into to the scientific philosophy and anxieties of an era. Realizing this, in fact, was what made me grow to love the novel. The first time I had read it for school, at fourteen, I complained bitterly the entire time, tripping over the archaic prose and frustrated with Victor’s terrible life choices. But rereading the novel as an adult, learning more about its social and historical context and Mary Shelley’s motivations in writing it, I felt as though I were filling in the missing pieces of a puzzle.

Oddly enough, much of what I was learning in HI482 about the history of palaeontology felt like it was filling in gaps in the same strange puzzle. As railways and mines invaded the sublime natural spaces that the Gothics adored, these works of excavation turned up more fossils than ever before; with the wealth of knowledge gained by studying these fossils, the field came into its own.

For much of history, the age of the Earth most widely accepted by the Western world was the Biblical figure of roughly six thousand years. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, all geological evidence was pointing to the fact that the Earth was actually formed an incredibly—inconceivably existentially terrifying—number of years ago. We tend to take this kind of “deep time” for granted nowadays, but if you really, truly think about it— if you place yourself in the shoes of an average Victorian viewing the dinosaur exhibit at the Crystal Palace for the first time, and learning that, countless aeons ago, the Earth was ruled by razor-toothed monsters—it begins to look something like a horror story.

This, I think, is precisely why the paleoart I love from this era feels so wondrously Gothic … and also why, while I was researching an essay on the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, I paused and asked myself:

What if a Victorian palaeontologist, some descendant of Frankenstein, rediscovered his notes and tried to “bring the past to life” in a far more literal way?

At first I laughed it off at first, thinking the question ridiculous, but over the next few weeks, it refused to leave me alone. Sheepishly, I proposed to my advisor that “Frankenstein-but-with-dinosaurs” could be a good idea to explore as my final year project, and to my surprise and delight, he agreed. Along the way, my main character, Mary—who began mostly because I wanted to examine Frankenstein’s themes of parenthood and ambition and rage from a female character’s point of view—rapidly developed a life of her own. Her personality spilled off the page; clearly, she had more story to tell.

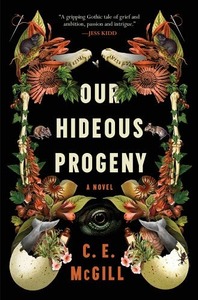

I never expected that I would turn Our Hideous Progeny into a full-length novel, but like any good monster, it crept up on be from behind and refused to let me go. My 14-year-old self would be shocked to hear the direction my career has gone, I think, but I’ve never been happier to take an unexpected turn. I can’t wait to see the story released into the world at last, and—in the words of Mary Shelley—I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper.

__________________________________

C.E McGill is the author of Our Hideous Progeny, available from Harper.