On Translating Michele Mari, an Italian Literary "Living Legend"

Brian Robert Moore Reflects on Bringing You, Bleeding Childhood to an Anglophone Audience

Children’s books, comics, puzzles, toy cars, soccer balls, illustrations, the lyrics of songs and lullabies: taken together, the stories in Michele Mari’s You, Bleeding Childhood represent a cataloguing of objects and texts, a crystallization—through the most personal artifacts—of a childhood, and with it, a life. A literary project such as this could no doubt be deemed obsessive, but for Michele Mari, the highest form of literature is, as he put it in one interview, the kind “that surrenders to its own obsessions.”

When asked what his own defining obsession was, he indicated the following: “That of living life as a continuous mourning for my childhood, for which I have a nostalgic, neurotic fixation. Not because it was a golden age—quite the opposite….But because it was the most meaningful thing I ever lived through.” Childhood, with all the terrible consequence of its joys and its pain, is revealed in the pages of Mari’s stories as an open wound, one that inevitably bleeds into and tinges the years and decades to come, so as almost to blot them out entirely.

Surprising as it may be for anglophone readers who are new to his work, Michele Mari—once a literary outlier in his native Italy thanks to his bookish phantoms and infatuations—is today seen by many Italians as a kind of living legend. His books, from the late 1980s onward, have prefigured disparate trends in literary fiction, from a general revival of the gothic and the fantastic, to the split selves that have come to characterize autofiction. And yet if Mari can now be recognized as an unlikely trendsetter at home, his work is less frequently considered in relation to his actual contemporaries as it is to distant models such as Poe and Melville, or Céline and Gadda.

Mari’s writing, with its tendency to mimic older authorial voices and styles, in many ways invites such a reading, employing what he himself calls a “literary vampirism” to explore what would be too crude, commonplace, or heartbreaking to talk about otherwise: a method that elevates these topics and, at the same time, renders them more bearable, if not hilarious. In other words, style enables a “process of redemption,” of regaining the upper hand on life.

This correlation between literature and real life, however, is not always straightforward. Before producing more overtly autobiographical work, Mari published three novels of the most fantastical and hyper-literary order. Beginning with 1989’s Di bestia in bestia (From Beast to Beast)—set in a gothic castle where a man hides both his immense library and his own monstrous twin—each of these early novels explores the theme of the double, of one’s own freakish or regressive other half.

Surprising as it may be for anglophone readers who are new to his work, Michele Mari—once a literary outlier in his native Italy thanks to his bookish phantoms and infatuations—is today seen by many Italians as a kind of living legend.

Although the theme might be less apparent in the book as a whole, perhaps it is only with his 1997 collection You, Bleeding Childhood that we discover a key motivating factor behind Mari’s recurring focus on the hidden other. From the very first story, the reader is presented with a Jekyll and Hyde scenario, in which an outwardly respectable—indeed, an outwardly grown up—professor decides he must hide away in order to give vent to his truest passions and reread his childhood comics.

Michele Mari’s comic book adaptation of The Cloven Viscount by Italo Calvino, 1972. Michele Mari, La morte attende vittime (Nero, 2019).

Michele Mari’s comic book adaptation of The Cloven Viscount by Italo Calvino, 1972. Michele Mari, La morte attende vittime (Nero, 2019).

While his use of literary pastiche has led Mari to be read in dialogue with venerated authors of the past—that is, with the “canon”—nowhere is the vast and unconventional nature of his own personal canon more evident than in this collection. By drawing most explicitly on the genres that made him fall in love with reading in his youth, Mari engages in a process of expansion and inclusion, subverting common conceptions of what counts as classic literature.

Throughout You, Bleeding Childhood, a refined and even archaic vocabulary melds fluidly with the lexicons, tropes, and traditions of numerous popular genres, plumbing the emotions a young reader might experience when first encountering infatuating and hair-raising works of horror or adventure, fantasy or sci-fi, not to mention folktales and myths, mysteries, westerns, nautical novels, and so on.

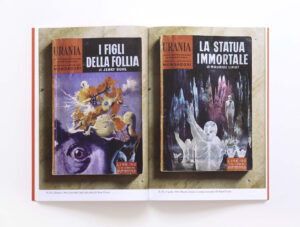

This ennoblement of what is often viewed as second- or third-tier literature is carried out continuously, from “The Covers of Urania,” an essayistic ode of love and terror to a sci-fi series that introduced the author to “the dark side of literature”; to “Eight Writers,” in which a supergroup of maritime writers must be disbanded, as they individually battle for supremacy in a heightened fan-fiction of the mind; or again in “Comic Strips,” where a literature professor realizes that his childhood comics, still contained in his extensive and invaluable library, hold an “eminence before which all the other books—the ‘real’ books, the ‘serious’ books—had to bow down.”

Such a statement shouldn’t be read as simply farcical or provocative: before enrolling in university and setting out to become a professor of Italian literature, Mari actually focused on drawing comics and graphic novellas, even garnering the praise of Italo Calvino. After receiving the sixteen-year-old artist’s adaptation of The Cloven Viscount—another bloody tale of a split individual—Calvino wrote, “I had great fun looking at your Viscount comic. Your way of narrating through images is full of witty and effective visual devices….I’m delighted by your work.”

Editions taken from Michele Mari’s collection of the sci-fi series Urania. Michele Mari, Le copertine di Urania, with photos by Stefano Graziani (Humboldt Books, 2023).

Editions taken from Michele Mari’s collection of the sci-fi series Urania. Michele Mari, Le copertine di Urania, with photos by Stefano Graziani (Humboldt Books, 2023).

Across Michele Mari’s oeuvre, these decisive books from his youth come together with other childhood relics to form a personal mythology. More than just symbolic items, they are fetishes, in the original sense of the word. Gradually, these artifacts also reveal themselves as prisms through which to view others; as talismans that house the essence not only of the author and his past, but also of his most formative relationships: grandparents, neighbors, classmates, and most importantly—and most frighteningly—parents.

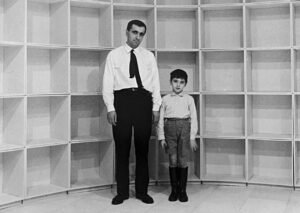

Of his parents, Mari would write at greater length in his partly fictionalized “horror autobiography” Leggenda privata (Private Legend), but the importance of these blood ties is first captured in his stories. Mari’s father was renowned industrial designer Enzo Mari, a domineering figure in reference to whom the author would write that his own “admiration was such as to prevent any healthy antagonism at its inception.” Already in a few chance anecdotes in the stories “The Covers of Urania” and “Down There,” this father betrays a clear taste for frightening his young son, recounting the unthinkable in a straight-faced manner that appears both scarring and, paradoxically, generous, as though imparting one of the greatest gifts for the development of the author-to-be (an author who is always dead serious even when deadly funny).

In “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”—one of Mari’s most Kafkaesque stories, insofar as it recalls the father–son dialogue and the terrible revelations presented in stories such as “The Judgment”—an imagined conversation between the two men acts as a near manifesto on the emotional power of personal objects. With the central figure of Enzo in this story, one can’t help but wonder how much his methodology as a designer and artist, who used household objects such as furniture, calendars, and even toys to convey radical ideas and political values, influenced his son’s tendency to see the items that filled the day-to-day of his formative years as more than merely material.

Enzo Mari and Michele Mari, at the Danese design showroom in Milan. Courtesy of Michele Mari.

Enzo Mari and Michele Mari, at the Danese design showroom in Milan. Courtesy of Michele Mari.

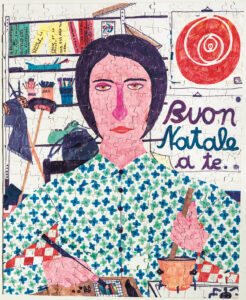

A less apparent but equally impactful presence is the author’s mother, the children’s book illustrator Iela Mari (née Gabriela Ferrario), who sets the tone and the subject matter of two stories in particular: “War Songs,” dedicated to the bloody and sorrowful mountain hymns of the Italian Alpini from World War I, which she would sing as lullabies; and “Jigsawed Greens,” in which the puzzles obsessively assembled by mother and son become, in a dizzying, Borgesian escalation, a vector for contemplating the infinite through the infinitesimal.

Though all but silent on the page, Iela is everywhere in these stories: in the references to mountains, for one, which are first used as a metaphor in “Jigsawed Greens,” before appearing in the songs of those Alpine troops. Iela had been a skilled mountain climber, an activity that became so detached from her married life that Enzo apparently didn’t even know about her passion—let alone that she had regularly climbed with the likes of Dino Buzzati, an author who originally made a name for himself with the novella Barnabo of the Mountains.

As Mari reveals in Leggenda privata, such stories seemed to pertain to a different Iela from before, with the pieces of his mother’s life appearing impossible to fit together: a mother characterized, in other words, by fragmentation, who already in You, Bleeding Childhood imparts a vision of the world broken into puzzle pieces, singing of a military captain who commands that he himself be “into five pieces cut.”

Jigsaw puzzle depicting Iela Mari, drawn and cut by Michele Mari in 1969. Photo © Francesco Pernigo. Michele Mari e Francesco Pernigo, Asterusher (Corraini Edizioni, 2019).

Jigsaw puzzle depicting Iela Mari, drawn and cut by Michele Mari in 1969. Photo © Francesco Pernigo. Michele Mari e Francesco Pernigo, Asterusher (Corraini Edizioni, 2019).

In contrast to the frantic anxieties that fill Mari’s paternal tales, in these two stories the narrator’s profound emotion and nostalgia are perceptible under an analytical veneer, an apparent coldness, as if to mirror a figure who is referred to elsewhere in the collection as the “Fake Mother,” one who, even when smiling, dons the emotionless mask of a body snatcher. While Mari evidently feared as a child that his real mother had been replaced by the hollow exterior of an extraterrestrial or pod person, in Leggenda privata he also points to the overpowering character of his father as having had a hand in turning her into what can only be described as a shell of her former self, writing “my mother was destined to be colonized, if not by a pod than by him, he who occupied people like a tenant occupies an apartment, renovating it according to the most rational laws.”

The English edition of You, Bleeding Childhood also includes two beloved stories from Mari’s 1993 collection, Euridice aveva un cane (Eurydice Had a Dog), which complement the recurring themes and obsessions of his 1997 collection: the accumulation and fetishization of objects, a preoccupation with the passing of time, and the impossibility of preserving the past. The first story for which Mari explicitly used his own life as his subject matter, the title story of Euridice also familiarizes readers with the much-mythologized house near Lake Maggiore where he spent his summers growing up, in a town first referred to as Scalna, and in later works called by its real name, Nasca.

“Scalna was never a town,” the story opens, and this line has been something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, with the house and its surroundings shifting over the years to mirror the inner life of the author. Scalna—that is, Nasca—is, today, not a real place but a ghost town, a hardly locatable hamlet where, although everything has closed, everything has kept still, with outward appearances remaining unchanged: on the walls along its main street, the painted words for the tailor or the trattoria are still legible over the doorways.

This place has stayed deeply tied to Mari’s autobiographical or autofictional work, becoming the setting of several moments in You, Bleeding Childhood, and returning in two of his most personal and horror-inflected novels, Verdigris (which And Other Stories will publish in 2024) and Leggenda privata.

Though he has split the majority of his adult life between his hometown of Milan and Rome, Nasca is nonetheless where Mari has done most of his writing, in that same library in which he all but entombed himself in his youth. If Mari wrote in “Eurydice Had a Dog” that he fantasized as a child about keeping everything exactly the same in his neighbor’s house so as to turn it into a museum, that is largely what he has done with his own home.

Through the rusted front gate and down the walkway, up the flights of creaky stairs: there, in the bedrooms, one can still find stacks of puzzle boxes and piles of old toys on the antique furniture; or, resting on the nightstand, a single Urania paperback, perhaps left there from the small hours of the night before, or from decades earlier.

Michele Mari’s house in Nasca. Photo © Francesco Pernigo. Michele Mari e Francesco Pernigo, Asterusher (Corraini Edizioni, 2019).

Michele Mari’s house in Nasca. Photo © Francesco Pernigo. Michele Mari e Francesco Pernigo, Asterusher (Corraini Edizioni, 2019).

______________________________

You, Bleeding Childhood by Michele Mari is available via And Other Stories.

Brian Robert Moore

Brian Robert Moore has translated A Silence Shared by Lalla Romano, Meeting in Positano by Goliarda Sapienza, and the work of other distinguished Italian authors. He has received a National Endowment for the Arts Translation Fellowship, a Santa Maddalena Foundation Fellowship and the PEN Grant for the English Translation of Italian Literature. His translation of the novel Verdigris by Michele Mari is forthcoming from And Other Stories.