On the Vital Importance of Preserving the Most Obscure—and Endangered—of the World’s Many Languages

Lorna Gibb Considers How Language Shapes Identities, Worldviews and Societies Across the Globe

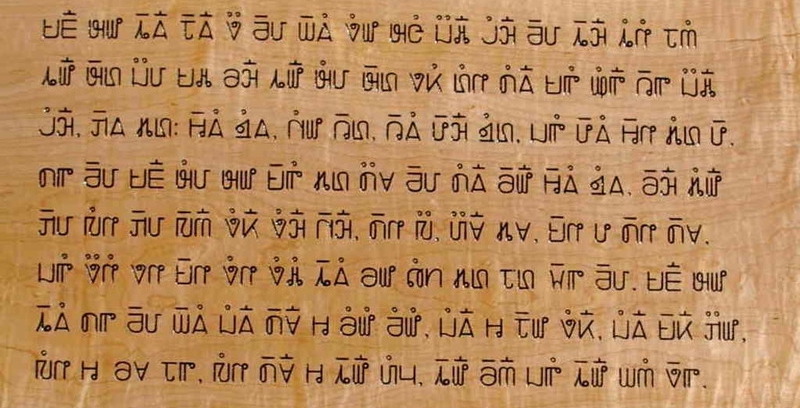

There are languages like German and Cantonese that will be familiar to you, even if you don’t know anyone who speaks them. But fewer will have heard of Hmong, the whistling language of the Himalayas. Or Guarani, the majority language of Paraguay, which is too often disregarded, despite being more widely spoken than Spanish in the country. Rare Tongues is a journey through some of the more esoteric languages of our planet and what they can tell us about ourselves and our more familiar languages.

Some languages I have studied and travelled to explore. Others have been chosen because of the crucial knowledge that they carry, knowledge that is in danger of being lost forever. Some of them have fascinating features that may make you question what we regard as a language at all. Others have turbulent histories and carry painful memories for those who dared to speak them amid political upheaval. And a few of them are under threat, their continued existence in question, because of creeping linguistic homogeneity, moving like a silencing killer across our landscapes, rendering words unspoken and forgotten.

Every language is unique and has something important to tell us about the world we live in. Each one of them can enlighten us about the manifold roles that they play in defining society, in enriching it, in enabling diverse communities to share knowledge and histories. This is what is at risk: when a language is no longer understood, an essential and inimitable way of seeing the world, of interacting with it, disappears too—and there is an undeniable link between the erosion of diverse cultures and climate change. Awareness is growing, but slowly. We are currently in the United Nations decade of indigenous languages (2022–2032), and activists and academics are highlighting what we still have and what we are in danger of forgetting. This book is my contribution to that chorus of voices: a personal call to reflect.

When a language is no longer understood, an essential and inimitable way of seeing the world, of interacting with it, disappears too.

Since childhood, I’ve been fascinated by languages. In the seventies and eighties, when I was growing up on a sprawling council estate in Bellshill, North Lanarkshire, Scotland, you didn’t hear many people who sounded like me in the media. However, I discovered, even before I went to secondary school, that I could have two different types of language just by copying people on the television. I didn’t use what my family proudly called “Lorna’s posh voice” very often, but I switched it on when I had to read something aloud at school or act in a play, or at the ballet school where I was the only kid from a council estate and it made me fit in better.

And it wasn’t just the variations of my native tongue. Before I was born, my mom was the manager of a record shop, and so I was raised on all kinds of music, but especially the operas of Puccini. I’d follow the Italian words in English on those dual-language scripts you used to get inside opera album boxed sets, while my friend, whose dad ran the local Chinese restaurant, taught me Cantonese phrases in the playground, which I proudly repeated at home in the evening.

When I moved to London to study for my first degree in English Language and Literature, I learned that what I had always thought of as upper-class accents and my own, very different, way of articulating at home were more than just a way of speaking: they were a way of being. The soft, persistent rain that I called “smirr” did not exist in London, and a phrase I might use with friends at home, teasing, “you silly cunt” or saying “cunts everywhere” to describe a busy street, represented something far stronger and more forbidden in my new home city.

I knew words that did not exist in Standard English and used them as part of my everyday vocabulary without even considering that people in London might not understand them. In a second year phonetics class, we spoke of sociolinguistics and how class and accent were linked, a fashionable theory at the time. Our phonetics lecturer asked me if I would stand up and say a sentence to a packed lecture hall, so that everyone could hear a Scottish working-class accent. I was embarrassed, already finding it difficult to fit in with most of my peer group, who were from far wealthier backgrounds than me and didn’t have to juggle learning with jobs to finance their studies. But I stood up anyway, and aggression, which came more naturally to me than tears when I felt cornered, made me say, “This is a really ridiculous thing to ask me to do” in the strongest accent I could muster. The lecturer, who was well-known, didn’t even have the awareness to blush, just thanked me and told me to sit down again.

Afterwards, though, I did come close to tears when I overheard two wealthy fellow students mimicking my accent and calling me the “Scottish charity case” when I walked past the common room.

Yet, conversely, the fact that I had studied five years of Latin at my very rough comprehensive school (because it was still regarded as a good thing to do in those days in Scotland) meant my first job as a cash-strapped student paid more for a day than I had earned in a month in my Saturday shop jobs at home. My English literature tutor asked me to help him translate some Medieval Latin texts for a book he was writing. It was a pleasure; I would have done it for half the cash, and he always arrived with wonderful cheese and a glass of good wine for our sessions. He brought in texts that we then worked on together, acquired a British Library reader’s pass for me (it was still located in the British Museum then), and watched with amusement while I fell in love with Medieval Latin bestiaries and their beguilingly beautiful gilded illustrations. It was the best job I ever had as a student; in fact, it was the best job I had for a good few years afterwards too.

All this happenstance and accident of birth consolidated into a curiosity about how humans communicate with each other. What makes languages different from each other? How are language and landscape and language politics related? Which aspects of language develop because of where we live and how we live? And why do some languages die? What does it mean when they do?

It wasn’t until I began my postgraduate studies in linguistics, or, more precisely, in phonetics and phonology, and began to look at the sounds of languages across the world that I realized just how diverse and fascinating, and filled with local knowledge and history and culture, these systems of sounds could be. Moreover, it wasn’t just a particular accent that people assumed was indicative of your birthplace, your class, and even sometimes, ridiculously, your intelligence. Rather, there were entire languages haunted by a huge collection of assumptions that people could and did make when they encountered them.

These assumptions could work for you or against you, in terms of where you were placed in society, who you were judged to be, and what opportunities were open to you. So, although Guarani is the most widely spoken language in Paraguay, its speakers there are presumed to be poor and uneducated, unlike Spanish speakers. But in the United States, first-language Spanish speakers may be ridiculed and discriminated against, even when they are perfectly fluent in English. And when Singhalese became the official language of Sri Lanka in 1948, Tamils could no longer work in the government or in the civil service, even though there had been Tamil speakers in Sri Lanka since the second century BCE. Colonization in its myriad forms often attempts to eradicate and forbid the use of the language of the colonized in the name of assimilation and education.

Wars have been waged over the right to speak a language and wars may also have the eradication of a language as an aim. But they can also be used to establish a common peace and wipe out nationalism. This is what happened in 2017 when the four languages of former Yugoslavia, that is Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian, were declared to be four different versions of a single language. In an attempt to suppress strong national identities that had led to years of war, thirty linguists from across all four countries testified to the statement, which was greeted with dismay and disbelief by nationalists but welcomed by most speakers in each of the countries, whose only question was what a single language might most fairly be called.

And it is not only the power of language, but also its variety that makes it fascinating. There is articulation—the way our lips and tongues and teeth and the shape of the inside of our mouths can fashion sounds that seem impossible to one person yet are part of everyday communication to another. There are the words that these sounds make and how we use them. There are the spoken and unspoken meanings behind them, the way these are perceived. There are concepts hidden in a sentence or a whole perspective on a philosophy of a way of living encoded in a single word.

Agglutinative languages see what English speakers think of as suffixes and prefixes as building blocks to create a single word with a different purpose, so that “in the flower,” which has three distinct words in English, becomes the single word “kukassa” in Finnish, with the ending “ssa” showing that the word is what’s called inessive and refers to something being inside the named noun. And there are the structures that dictate the order in which words should appear, sometimes with a verb at the end, such as “Je t’aime” in French, or sandwiched between subject and object, as in “I love you.”

Many Asian and African languages are tonal—that is, the meaning of a word is conveyed by pitch rather than by a series of sounds. The word “ma” in Mandarin can mean “mother,” “horse,” or “to scold,” depending on whether your tone is level, high then low then high again or falling. The distinction is clear to a Mandarin speaker, yet the three words will often be indistinguishable to a speaker of an Indo-European language, such as Italian, German, English, or Hindi. Yet when, in accordance with his parents’ regional tradition, I was invited to choose an English name for my Chinese godson, I avoided any with the phonemes /r/ and /l/, opting for my late dad’s name, John, because I knew that neither of his parents, despite their excellent command of English, had ever mastered those particular sounds.

And landscape, the geography of where we live, can shape our communication too. Languages that are whistled rather than spoken exist in mountainous regions around the world. Historically, one language grew from Native American signing languages in the Great Plains of the eighteenth-century United States to meet the need for different linguistic communities to speak to each other; it went on to become one of the most important languages used for trade and inter-community exchange in the world.

And while our environment can shape language, those same words often carry information about the land and all that live in it. The loss of a language, therefore, can mean the disappearance of unique ecological knowledge. By revitalizing and promoting a multitude of tongues, linguistic activists are preventing rich and important knowledge about our world from being lost forever.

*

Languages can be the gateway to secret groups, societies, and clans and become the basis of criminal masterminding, allowing their speakers to discuss schemes and plots without fear of discovery. The language of the Hmong people in the Himalayas may be used to find a mate, and afterwards may grow and be adapted into something shared only by the couple who used it in their courtship, akin to the languages shared by twins as children, known and understood only by the two people who have created it.

I’ve come to see that these rare tongues are intricately composed musical notes in the symphony of our human experience.

When I began writing Rare Tongues, I was working and living just outside London. But then the pandemic happened, bringing new realizations of what is most important and new ways of working that, in my case, meant being able to be closer to family. So I returned to my linguistic beginnings, to Central Scotland. My accent grows stronger, day by day. I relearn words that I had stopped using because English friends and colleagues could not understand them. “Dreich” (grey, wet, miserable weather), “greetin” (crying/weeping), “chappin” the door instead of knocking, “bletherin” (either idly gossiping or saying something nonsensical or untrue), “hingin aboot” (waiting), and “scunnered” (sickened) are, once again, words I hear and use every day.

It feels as if I am coming home to my own tongue as well as to my kin: it brings awareness and sorrow for those who may never experience that, because their mother tongue is no longer spoken or in decline, and happiness that my own Scots language, my mother’s tongue, is now on the rise, with young, brilliant, creative people sharing it as a badge of pride, and a new understanding of nuance and expression. I find myself grinning when I come across a phrase I haven’t heard for years: “Ma heid’s birlin” (My head’s spinning), “Away n bile yer heid” (Get lost), “Gie’s a lenny that” (May I borrow that?). And at first, I was also slightly amazed that I understood them immediately, without any hesitation at all, as if they were somehow imprinted onto who I am linguistically. This persistence isn’t true of languages I’ve worked hard to learn. Despite living in Finland for almost two years, and once having a reasonable fluency in the language, I can barely manage a sentence in Finnish any more and can no longer understand even the simplest WhatsApp message from old friends without recourse to an online dictionary. With age, there is also a realization and sense of regret that I will never, ever achieve anywhere near the level of fluency in the other languages I know as that which I possess in my native tongues.

The intricate dynamics of language evolution, conflict, and extinction can serve as a microcosm for the broader sociopolitical landscapes in which they exist, illuminating how unusual, threatened, and extinct languages are not merely footnotes in linguistic catalogues but vibrant markers of cultural identity and historical evolution.

In my own journey, I’ve come to see that these rare tongues are intricately composed musical notes in the symphony of our human experience. These are not mere words and syntax but the keepers of unique worldviews, the battlegrounds of ethnic clashes, and the cries of societies struggling to preserve their heritage. Each one carries deeply personal stories; each one is a living testament to human resilience, adaptability, and the enduring quest for identity in a rapidly changing world.

__________________________________

From Rare Tongues: The Secret Stories of Hidden Languages by Lorna Gibb. Copyright © 2025. Available from Princeton University Press.

Lorna Gibb

Lorna Gibb is associate professor of creative writing and linguistics at the University of Stirling. Her books include The Extraordinary Life of Rebecca West, Lady Hester: Queen of the East, and the novel A Ghost’s Story. Her writing has appeared in leading publications such as Granta and the Telegraph.