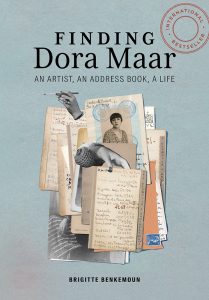

On the Untold Talent of Dora Maar, More Than a Muse of Picasso

In Search of "The Weeping Woman"

Dora Maar. At first, only the photographs came to mind: Picasso naked to the waist, Picasso in his striped swimming trunks, Picasso painting Guernica . . . And then, all those paintings he did of her, depicting her as “the weeping woman,” disfigured, devastated by grief.

Thank goodness for Google. I surfed, I clicked, I did not read so much as devour: “Dora Maar, French photographer and painter, Picasso’s mistress . . .” “Dora Maar, from her given name Henriette Theodora Markovitch, born November 22, 1907, in Paris . . .” “Only daughter of a Croatian architect and Touranian mother . . .” “Spent her childhood in Argentina before returning to live in France . . .” “Friend of André Breton and the Surrealists . . .” “Mistress of Georges Bataille . . .” Dates, cities, names. “Dora Maar, remarkable twentieth- century figure . . .” “Profoundly original style . . .” And always the references to Picasso: he “loved other women more passionately, but none had so much influence over him . . .” “Picasso pushed her to give up photography . . .” “Picasso left her for the younger Françoise Gilot . . .” Snippets from a life, flashes of suffering: institutional- ized, electric shock treatment, psychoanalysis, God, solitude. So the woman who owned this address book had been Picasso’s companion for almost ten years, from 1936 to 1945. Before him, she had been a great photographer. After him, a painter who sank into madness, then mysticism, and finally reclusion.

I had fun making a list of the adjectives attached to her, hoping that a portrait would emerge from this cloud of words: beautiful, intelligent, shy, willful, volatile, quick-tempered, haughty, unyielding, impetuous, proud, cultivated, authoritarian, snobbish, vain, mystical, mad . . .

Most of the newspaper articles about her dated from her death in 1997 and the sale by auction of her estate: 213 million euros divided up among experts, auctioneers, genealogists, the state, and two distant heirs in France and Croatia who had never met her.

In the end, I wrote down this sentence, copied and pasted so often on the internet I don’t know how to credit it: “She was Pablo Picasso’s mistress and muse, a role that eclipsed the entirety of her work.” A cruel legacy that preserves only the role of mistress and casts an entire life’s art in the shadow of a giant. Cruel but irrevocable.

Who knows Dora Maar’s work? Who remembers that she was one of the rare women photographers accepted among the Surrealists? Who recognizes that she devoted sixty years of her life to painting?

“She was Pablo Picasso’s mistress and muse, a role that eclipsed the entirety of her work.”

Her most famous photographs are the portraits of Picasso. But the most astonishing ones come earlier: dreamlike experiments, Surrealist collages, shots capturing social issues. Before she had even met the Spanish painter, she was more famous than her friends Brassaï and Cartier-Bresson, and she had not yet turned thirty.

Even today, collectors and major museums fight over her prints at auctions. But that is not the case with her paintings, to which she attached much greater importance.

Many authors have already examined her fate: a few serious biographies, some novels loosely based on her life, and many art books. They are almost all written by women, fascinated by what became of her and the mystery of a tragic heroine who, like Camille Claudel or Adèle Hugo, devoted and abandoned herself to passion. And here I was, joining their ranks.

She must have started entering names in the address book in January 1951. In Paris, an icy wind was blowing from the north. It snowed for New Year’s Eve. On rue de Savoie it must have been very cold, especially since she had a tendency to scrimp on coal. From the leather writing case on her mahogany desk, she took one of the quill pens that Picasso had given her. Nothing had been moved in six years. She still slept in the Empire bed where they had made love and still lived among his gifts, his paintings, his sculptures, his little makeshift constructions that she stashed in drawers. Above all, she hadn’t repainted the walls; it would be sacrilege to cover over the insects that the master had drawn in the cracks to amuse himself.

I imagined her carefully filling the small booklet page by page.

She would have begun with the As, then moved on to the Bs. But without strictly following alphabetical order. She must have used this occasion to make a selection; the friends who betrayed her no longer warranted an entry. Sometimes she hesitated: What was the use?

Sometimes she kept them as one keeps a photo or a memento. The hardest to eliminate were the deceased, who must have seemed like ghosts from the oldest address books. By deleting their names, she buried them one more time.

This address book was a snapshot of her world in 1951: layers of friends and acquaintances accumulated over the years, and a few new ones, surely. But who really mattered in this list? Who telephoned her? What numbers did she dial? If someone found our smartphone contacts today, wouldn’t they see our favorites, reconstruct the history of our calls, read our texts and emails, listen to our messages? They would know our entire lives. This book of hers was silent as the grave. Nevertheless, it could speak of the delicate hands, fingernails forever polished, that slipped it into or retrieved it from her handbag. It could name her true friends. It could remember conversations, confidences, arguments, laughter, or tears, for which it was the only witness. It could also recall her moments of solitude, when it sat there closed, it and the cat her only companions.

The living room at the rue de Savoie address had become Maar’s studio. She shut herself away there for entire days at a time, or even longer. “I must dwell apart in the desert,” she told a friend. “I want to create an aura of mystery about my work. People must long to see it. I’m still too famous as Picasso’s mistress to be accepted as a painter.” She understood that she would have to reinvent herself, erase “the weeping woman,” and write another story.

But she also had to retreat when she couldn’t bear it any longer—bear either herself or what she was painting. When she could no longer tolerate either isolation or the company of others. When she refused to be seen as less than beautiful, her face drawn, her eyes puffy. She was so proud.

I can also see her turning these pages, not even thinking of making a call, just to reassure herself, to remind herself that she knew everyone! And the names filing past gave her the illusion of bumping into friends. Then she would force herself to try calling a gallery owner again, call her hairdresser, her manicurist, or just an acquaintance.

In the past, Picasso had always called when he decided to have lunch at the Catalan, a Spanish restaurant halfway between their two homes. He would say, “I’m leaving, come down,” in that inimitable accent he never lost. At his signal, Dora the arrogant, Dora the proud, would grab her bag, tear down her two flights of stairs, and meet him at the street corner. Often she waited. If by chance she was late, he never waited, of course, but would save her a place at the table. In 1951 she was still going to the Catalan, but no one summoned her to dessscendrre in that tone of his. She wouldn’t have stood for it anymore! Or else, only from God! Yes, “after Picasso, there can only be God,” as she said.

Searching the internet, I discovered an account by her last gallery owner. On the La Règle du jeu site, Marcel Fleiss offers an astonishing story of his meeting with the elderly woman in 1990, and how her last exhibition was organized. His email address was listed on his gallery website. And he answered immediately: “Come see me at the FIAC!” The very next day, I slipped Maar’s address book into a small leather case and clutched my handbag firmly on the metro. Arriving at the Grand Palais, I tried to act natural, like a conspirator concealing a valuable treasure.

__________________________________

From Finding Dora Maar by Brigitte Benkemoun, translated by Jody Gladding. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Getty Publications.

Brigitte Benkemoun

Brigitte Benkemoun is a journalist and writer. She is the author of La petite fille sur la photo (2012) and Albert le Magnifique (2016).