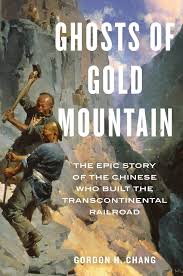

On the Unsung Lives

of the Chinese Laborers Who Built the Railroad

When Two Railroads—and the Migrant Workers Who Built Them—Met

In the fall of 1868, Charles Crocker estimated that 10,000 Chinese, 1,000 whites, and “any number” of Native Americans worked for the Central Pacific Railroad. Crocker and other company leaders had little direct contact with, let alone understanding of, the men who were actually building the railroad for them. Crocker confessed as much when a San Francisco reporter asked him about the work in Nevada. He said that in addition to Chinese and whites, he had hired men from Native tribes in the Humboldt channel to work for the company. He admitted that he did not know how many were employed because “no list of names was kept” and the men worked in “squads and not as individuals.” Besides, Crocker ignorantly offered, “Indians and Chinese were so much alike personally that no human being could tell them apart.”

Perhaps because he viewed them as racially alike, he seems to have used them similarly. To avoid making the mistake of paying an individual twice, he said, the company devised a “scheme of employing, working and paying them by the wholesale.” Overseers counted how many went to work, ate, and then returned to camp at night. The company then paid the overseer, who in turn divided up the wages among the men. Crocker proudly claimed that his method avoided “lengthy bookkeeping,” saved time, and prevented “cheating.” It was also a method that kept both Chinese and Native American workers nameless and anonymous to the company.

Chinese and Native peoples in the American West had a close and complicated relationship. Records show more than 20 incidents in which Native Americans attacked and killed Chinese miners in the California gold country in the 1850s. When the railroad entered central Nevada, local Shoshones reportedly took potshots at the Chinese, and Charles Crocker also circulated a story about efforts by Piutes to scare Railroad Chinese from working. He said that Native people had told the Chinese about enormous reptiles or human monsters that hid in the desert and were so large they could devour a human in a single bite. Frightened by the stories springing from the Nevada desert, a thousand Chinese supposedly deserted the line and had to be wooed back by the company. Crocker seemed to relish the story as it simultaneously highlighted Chinese ignorance and gullibility as well as Indian maliciousness.

In contrast, other pieces of evidence suggest that Chinese and Native peoples developed cooperative, even intimate relationships. Archaeological evidence from living sites of Chinese and Native people point to trade between the two groups. Interviews with Native Americans and Chinese through the years also include stories of close, friendly interaction along the railroad that occasionally included intermarriages that produced children. An unusual and compelling story is handed down through the Lee family of New York about how their railroad worker ancestor survived an Indian attack that left many Chinese dead. He was spared as the tribal chief, who had recently lost his own son, took an interest in the strapping young Chinese man and brought him to live with the tribe for two years before releasing him.

Several unfortunate mules were caught in the cross-fire and were decimated by the blasts.Stories of interactions between Railroad Chinese and Irish workers are much more fraught. Hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrated to the United States beginning in the 1840s, and reports of conflict between the two immigrant groups during railroad construction have circulated widely. Many Irish traveled to the Far West, and by the 1850s they had become a prominent part of California’s population at the same time Chinese were arriving in the state. In 1860, the Irish were the second-largest foreign-born group behind Chinese, though the Irish population grew much more quickly, and they soon outnumbered Chinese. In 1867, San Francisco even elected its first Irish mayor, and the Irish continued to be active in politics, becoming a major element in the anti-Chinese labor movement that festered in the 1860s and exploded in the 1870s and 1880s. In railroad work, Irish formed a large proportion of the workforce for the Union Pacific, but hundreds also joined the CPRR as laborers, skilled workers, crew leaders, and supervisors. Mormons also came on the CPRR as it approached Salt Lake City, but there is little known about any interaction between them and Railroad Chinese.

Incidences of serious violence between the Irish and Chinese erupted as the lines of the rival CPRR and UP approached each other in Utah. In February 1869, a Utah newspaper reported an incident in which Irish workers used pick handles and explosives to attack the Chinese, seriously injuring several. The attackers ignored a company order to stop but found that the Chinese were a tough adversary. Chinese workers retaliated by setting loose their own blasts of dirt and rock against the Irish. A news report described Chinese as fighting with “unexpected vigor and accuracy.”

Fighting between the Union Pacific’s Irish and Chinese flared again two months later. Irish workers initiated fighting when they detonated explosions in the direction of the Chinese and seriously injured several. After Chinese responded with their own explosions directed at the Irish, the fighting stopped. Another report from early May 1869 recounts a similar incident, but with workers this time using nitroglycerine against each other. Several unfortunate mules were caught in the cross-fire and were decimated by the blasts. The two sides reportedly went to get firearms, but the fighting stopped before shooting could begin. Through it all, the defiant Chinese reportedly gained “due respect” from the Irish. It is a minor miracle that no loss of life on either side occurred during the mini-war.

In late May 1869, the national periodical Harper’s Weekly devoted extensive space to covering the completion of the Pacific Railway and offered a different narrative of the relations between Chinese and Irish, one that emphasized interethnic connection. The periodical dramatized the completion of the railroad work in Utah with a detailed illustration showing many Chinese and “European” workers blasting hillsides and grading for the roadbed. They appear to be working in coordinated fashion, though also in conflict. In one corner of the illustration, a group of whites torment a Chinese by pulling on his queue. The caption of the image declares that it shows the “mingling of European and Asiatic laborers” in constructing the last mile of the Pacific Railway, and the accompanying article hails the efforts of the two immigrant groups. A “medley of Irishmen and Chinamen” completed the rail line, Harper’s declared, and “typify its significant result, bringing Europe and Asia face to face, grasping hands across the American continent.”

“It was just like an army marching over the ground and leaving the track behind them.”To push the work even further, the two companies pitted the workers against each other in competitions. In August 1868, Railroad Chinese had laid six miles and eight hundred feet of track in a single day. After UP workers also completed six miles of track in a day, Crocker claimed his teams could lay ten miles in a day. Thomas C. Durant, vice president of the UP, bet they could not do so. The ensuing construction challenge became legendary in railroad history, as ten miles of track in a day had never been accomplished before. Top leaders from both companies ventured out into the desert to watch the contest, which would enter history not only for the amount of ground it would cover but also for how much closer it brought the CPRR—and the Railroad Chinese—toward the end of the line.

*

On April 28, 1869, at seven in the morning, a train whistle marked the start of the CPRR army’s work and the first supply train moved forward. The CPRR had prepared for the effort by loading five trains of sixteen flatcars each full of supplies. Each train carried enough material to cover two miles of track. Chinese had also distributed thousands of ties along the route in advance. Railroad Chinese unloaded kegs of bolts and spikes, fasteners, and iron rails from the sixteen flatcars in just eight minutes, and the supply train pulled away, letting another take its place.

Six-man teams then lifted small flatcars onto the track and loaded them with the rails and other materials that had been off-loaded. These horse-drawn cars were especially designed to slide the heavy iron rails off on rollers to be brought to the end of the completed line. There, Chinese unloaded the bolts, fasteners, and spikes, and two four-man teams of Irish workers lifted the 560-pound rails onto the ties. Chinese returned to straighten the track, drive the spikes into the ties, and bolt the fasteners. Four hundred Chinese followed and, using shovels and tampers, set the track firmly into the roadbed ballast. The small flatcars rolled back and forth along the rails to keep supplies moving.

Sometimes they had to be lifted off the track to allow a fully loaded car to come forward. The line was a flurry of activity, with an uninterrupted flow of supplies, workers, foremen on horseback, and carriers of food, water, and tea under the blazing sun. The army laid a mile of track an hour, and at midday, with more than six miles of track laid, it was clear that they would win the challenge. At 1:30, the troops stopped to eat. The location was honored with the name “Victory.”

A camp train pulled up to serve meals to 5,000 workers. Did the Chinese eat boiled beef and potatoes, as was the usual fare for whites, or did they have their familiar food? We do not know, but the food was served punctually, and soon the workers resumed their advance. Among the lunch guests attending the unprecedented event was a U.S. Army officer, who shared his observations with Crocker. He said he had never seen such organization as he had witnessed that morning. “It was just like an army marching over the ground and leaving the track behind them,” he praised. “[I]t was a good day’s march for an army.”

Tomorrow would be another workday for the “Asiatic contingent of the Grand Army of Civilization,” as they were called in the press.The ten-mile line was not just put down on flat ground but had to ascend the slope of Promontory Mountain. There were also curves that required tedious effort to bend the rails manually and attend to the particulars of the roadbed. The railroad army finally concluded its labors at 7:00 p.m., 12 hours after work began in the morning. The workers had handled 25,800 cross-ties, 3,520 iron rails, 28,160 spikes, 7,040 fishplates (a type of fastener), and 14,080 bolts and brought the CPRR three and a half miles to the east of Promontory Summit, the point where the lines of the two companies were to meet. As one journalist described it, several thousand Railroad Chinese and eight Irish rail handlers, “with military precision and organization,” had laid 10 miles and 56 feet of track in less than 12 hours, a stunning performance that had never been seen before. A San Francisco newspaper declared the feat “the greatest work in tracklaying ever accomplished or conceived by railroad men,” and a railroad historian later described the Chinese effort as “the most stirring event in the building of the railroad.” Celebratory accounts both then and since, however, included the names of the eight Irish iron movers but not one of the Chinese.

After the end of work, a supply train brought 1,200 men, almost all of them Railroad Chinese riding on flatcars, back to their camp at Victory, near the shores of the Great Salt Lake. Tomorrow would be another workday for the “Asiatic contingent of the Grand Army of Civilization,” as they were called in the press. A week after the challenge, the CPRR sent almost all of the Railroad Chinese back westward to improve the completed line. Only a small force of workers stayed near Promontory to lay the last length of track. It is largely for that reason that few Chinese were present at the ceremony that would occur at Promontory Summit, where Congress on April 9, 1869, determined the two lines would meet.

A few days after they had recovered from the ten-mile construction feat, some Chinese—Hung Wah, perhaps, and maybe a few others—decided to take a break. It may have been Sunday evening, a day off. They went to a bluff near Monument Rock, Utah. It was spring, and the vista must have been magnificent. They could see the rail line they had helped complete and, beyond it, the Great Salt Lake. It was a perfect place to enjoy the brown-glazed stoneware jug of Chinese rice wine they had brought along. It had come to them all the way from the Pearl River delta.

Astonished at what they themselves had done in laying ten miles of track in a day, they might have reflected on their triumph over the odds, taken pride in their achievement, and celebrated. They also knew the CPRR would soon meet the Union Pacific line, and Hung Wah and the others may have reflected back on the years of toil and speculated about what they might do next with their lives in the months and years ahead.

They might have become melancholy on the wine and thought about loved ones separated, far away in the villages, and their desire to return home. Or they might just have celebrated the coming end of railroad work and the chance to drift back to Truckee, Elko, or even San Francisco, where they could enjoy good food, attend an opera performance, or visit a “pleasure palace” that offered fresh opium and women. Bawdy joking and storytelling may have ensued. Done with the drink, they left the empty bottle and returned to camp. There was still work to do in the days ahead. Almost 150 years later, archaeologists studying the ground along the Transcontinental line stumbled across the jug intact, sitting on an outcrop. It had no written message inside, unlike those corked bottles that float for years in the ocean, waiting to wash ashore to tell a story. This bottle, though mute, had something to say. We just need to heed our imaginations and listen.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad. Used with permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright © 2019 by Gordon H. Chang.