On the Trail of a Murder in the

Dakota Badlands

Sierra Crane Murdoch Meets a Woman Who Takes Matters Into Her Own Hands

Lissa Yellow Bird told me that to find a body in the badlands, I would have to know the landscape in all seasons. I should be there when the snow melted in April, and when the heavy rain in May carved rivulets in the gumbo and washed sediment into the channels that cut around the buttes. I should see the cottonwoods bud in the late spring and, in the summertime, watch the cockleburs grow thick in the coulees.

The foliage would not last long, Lissa said. By late summer, the brush would turn brittle, so that a cigarette flicked out a car window might cause it to burn for days. In the fall, the rain would come again, and this, too, I should see: how the bentonite clay would glisten like whale skin, evening its own surface, filling the tracks of animals imprinted during the summer and fall before.

The winter was also important, when the snow would bring the land into full relief, and I would notice shapes that in other seasons I had overlooked. The badlands were never the same, Lissa said. They were always slumping, folding in on themselves. The land would reveal what it wanted to us. The point was not to force the land to give up the body but to be there when it did.

*

I visited Lissa regularly in the years after we met. I would fly to Fargo, where she would pick me up at the airport, and where I would spend weeks at a time tracing the paper trail of her life. That first winter and spring of 2015, I stayed with Lindsay or slept on the floor of Lissa’s apartment. Then summer came, Obie moved out, and Micah repainted the spare room for me. In the fall, Lindsay moved back in, and I returned to the floor. CJ found a girlfriend, who also slept on the floor awhile; and Obie came home with a girlfriend, too, and they shared a room with Micah. By then I had decided the apartment was full and rented a room of my own.

I accompanied Lissa to the reservation for the first time in April 2015. We met in Fargo, where I helped pack the car with tents, blankets, changes of clothes, flashlights, Coleman lanterns, Band-Aids, phone chargers, and a set of camouflage radios. We left the following morning after dawn. There was hardly room for Micah or Waylon, Lissa’s cousin, who rode on a mound of Pendletons in the back.

Waylon was so skinny his cheeks caved in. He had spent the recent months in jail, and Lissa thought this had done him good. His skin had color, she noted approvingly, and he was sober, praying a lot. He had spent the night before we left binding a fan of sparrow hawk feathers with a strap of leather that belonged to his late mother. “Everything I have of hers I’m slowly giving away,” he told me. He had gifted the fan to Lissa, who stuck it in her visor like a toll ticket. It quivered angelically above her head.

The trees were budding, a green blush along the edges of the highway. Waylon tapped on a drum and now and then burst into song, Lissa murmuring the words. I would soon learn that driving to the reservation put Lissa in her best mood. She told more jokes, smoked fewer cigarettes. “You’ll see,” she said. “I think there’s this nervousness, all this energy. It feels like my insides are tuning up to a higher frequency, so when I get there, I’ll notice things. It’ll happen to you. All these things we’re driving by, they’ll come into focus, and you’ll think, Wow, there’s a million places this kid could be.”

She turned to Waylon. “I brought some of that smudge so we can get that evil off you,” she said. Jails were full of bad spirits, and she didn’t want any tagging along. Waylon nodded and pointed out the window to an embankment. “Look at all those sweat rocks, Cuz! Load ’er up.” He was always collecting from roadsides, he said. Wood. Feathers. The quills of flattened porcupines.

By dark we had covered four or five miles and seen no signs of a body.

“Have you ever knocked one out with a tire iron?” I asked.

Waylon cackled. “Nah. That’s funny though. Wake up and find out they’ve been rolled for their quills.”

We began by the Little Missouri River, where the bridge crossed north of Killdeer into the badlands of Mandaree. There was a cattle guard at the entrance to the allotment and a red gate fastened with a chain. Lissa woke Micah, who opened the gate and followed us on foot to the riverbank. A dry winter had reduced the river to a trickle. We walked over sand and silt, through grass and the winter skeletons of chokecherry bushes, to where the river parted like loose strands of a braid. There, in a clearing, was a set of wooden pallets, the ground littered with bullet casings. A target had been nailed to one of the pallets and shot through a couple dozen times.

“Oil workers?” I asked. A rig was perched on the cliff above. “Yeah, probably,” Lissa replied. “Or rez kids playing around.”

She walked the perimeter of the clearing and then cut through the brush into a small grove. I followed and saw that she had paused. “Oh, come look,” she said. At the trunk of a tree were two coyotes, shot and laid like dogs in the shade. They had small wounds above their front legs, each crusted with maggots, but otherwise, they might have been alive. Their coats were glossy and thick, and they lay to opposite sides, their legs extended toward the river so that the spaces between their eyes were touching. Had they arranged themselves to die this way, or had the hunter put them there, I wondered?

We spent the whole afternoon like this, no pattern to our searching.

Lissa seemed guided by whim, and then by instinct, and then by some mysterious calculation. She dug her boots into the ground to test its softness. She pulled up deadwood to see what was beneath. When she came to a clearing or a coulee, she paused and said, “This isn’t right,” or, “This is the kind of ravine I was telling you about, where the ground is easy to dig.” She was always pointing to anomalies in the land—sunken patches of earth, sticks unnaturally piled so that they had to have been laid by humans.

We left the riverbank and climbed a series of draws toward the cliffs, where the silt became clay and the ground hardened. A creek cut around a plateau, forming a ravine into which Lissa descended. She was hardly graceful. Her feet stabbed the dirt like anvils, and she wobbled on steep terrain, but she was quick. I followed her along the creek through a mess of cattails, leaping over mud onto islands of sand. The ground was scored with the tracks of foxes, rabbits, ermine, and raccoons, and the brush along the channel was garnished with bits of fur. It struck me that KC, if buried here, was hardly alone. To the side of the channel, beavers had built and abandoned a lodge, which had sunken into the hill like a grave.

By dark we had covered four or five miles and seen no signs of a body. I had not expected to find KC, but I was surprised that the process soothed me, an enormous task reduced to small movements. It seemed to have a similar effect on Lissa. She was quiet on the drive that evening, pulling thoughtfully on her cigarettes. We stayed the night at the casino, where I made a bed for myself on the floor of our hotel room.

Waylon and Lissa were gone most of the night, gambling their free players’ cash and chatting with the guards, and when I woke in the morning, Micah was cocooned in the sheets of one bed and Lissa was fully clothed, lying prone on the quilt of the other. Waylon had not slept at all. After we had awakened, he announced proudly that one of the guards happened to be his cousin and had hooked us up with breakfast at the casino buffet. Waylon ate three steaks and fell asleep in the car.

Snow had fallen overnight. As we drove south along the lake, through rangeland toward the Little Missouri, the sun lifted and the snow vanished. The noise of the casino had fallen away—a couple had been arguing in the room next door. We wound on a dirt road through a shallow valley and came to a bluff overlooking the river.

We walked most of that day, up and down the bluff and through ravines that narrowed toward the cliffs. Micah found a puffball, which he gave to his mother to use at sun dance as a coagulant to heal from piercings. Lissa found a patch of bitterroot on the river’s edge, which she harvested by plunging her arm into the muck. Waylon gathered feathers. His traditional name was Picks Up the Feather, and Lissa liked to call him by variations on the theme. “Hey, Eats Ham Sandwich,” I heard her say at lunch in her lowest medicine man voice. Waylon did not always play along, but this time he taunted in reply, “Shops with Credit Card,” and Lissa laughed. Waylon did not have a bank account, let alone a credit card.

That evening, as we returned to New Town, I asked Lissa if she had ever seen a dead body apart from those of friends and relatives at funerals.

“Yeah,” she said. Briefly, in college, she had enrolled in a program to prepare for medical school, and in class, she dissected a cadaver. “There was this one woman who committed suicide. She drank Drano. Can you imagine? She still had nail polish on her fingers and toes. We weren’t supposed to take the shroud off their faces, but one day I couldn’t stop myself. I brought sage in and wiped her down and thanked her. It was such an intimate thing, you know? I’m going to let you dig through my stomach, through my reproductive system, through my brain matter.”

“What did you think when you saw her face?” I said.

“I remember looking at her and thinking, ‘Why did you do that? What could be so bad in this life?’ You read that someone killed herself with Drano, and you think that behind that shroud you’re going to see this horrible face—twisted, eyes swollen from crying 20 years. You think it’s going to be this terrible life written on a face, and then you lift it up, and it just looks normal.”

Lissa drove slowly, peering past me into the woods alongside the road. The trees grew thickly here, trunks tangled, buds sprouting new green. Every landmark reminded Lissa of something she wanted to tell me: discolorations in the soil, where water collected and evaporated to salt; the year-old tracks of an excavator pressed like fossils into clay; bones, bleached white, of various animals. “If you ever need to clean a bison skull quick, just put it on a hill of fire ants,” she said. Waylon and Micah had fallen quiet in the backseat. I heard Micah sigh. “Oh my God, Mom. I just want a freaking flush toilet,” he muttered.

Many families were desperate for the sort of help Lissa could provide, and word of her benevolence had spread.

Lissa sat up, pinched her eyes in such a way that I knew she was thinking.

“Hey, Mom,” said Micah. “What?”

“Why’s the lake named Sakakawea?” “You know who that is.”

“That wasn’t my question.”

“She helped Lewis and Clark, remember?” “Was she Arikara?”

“I think she was from further East,” I said. “She was kidnapped by Hidatsas.”

Micah stared at me, his face unexpressive. “Who taught you history?” he said.

“Then she had a baby with Lewis and Clark,” added Waylon. “Which one was it?” asked Micah.

“I don’t know. Both?” Waylon said.

Lissa laughed. “And that was when human trafficking all began on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation.”

“Ayyyee!” Waylon cried.

I was laughing now, too. Micah held his head in his hands. Lissa’s cigarette jittered between her lips. We were still laughing when we turned a corner and saw a car ambling toward us—two men, both tribal members, the passenger holding a gun. Lissa slowed to watch the men pass. She lowered her chin, narrowed her eyes at the driver.

“Mom. The toilet,” Micah said.

Our time together was often like this. Lissa would say something that made us laugh so hard our bellies hurt, and then she would go quiet, reproachful, as if we had stumbled into danger. Driving with Lissa on the reservation made me feel electrified. Her moods shifted wildly. I rarely knew where we were going, or why we went to the places we did. If I asked, Lissa often would not tell me. She would act as if I should have known, or as if she had said it already. I started asking fewer questions.

I stared out the window, answered her demands. “Find my lighter,” she would say, or, “Do I have any more cigarettes?” and I would go rooting through the console, through instant coffee and pill bottles and phone chargers and sage, until I found what she was looking for. With anyone else, I would have felt annoyed, but with Lissa, I felt like a wingman. She made every task seem important, as if we were on some covert mission, which, in a sense, we were.

By then her efforts to find KC were well known on the reservation, and it seemed to Lissa that more people than before were willing to help by joining searches and reposting her announcements on Facebook. She owed this willingness to the fact that James was in custody and Tex no longer in office, but there was, perhaps, another reason: Many families were desperate for the sort of help Lissa could provide, and word of her benevolence had spread.

The winter before I met Lissa, a tribal member named Robin Fox had gone missing, abandoned on a snowy night by a companion. A domestic violence advocate on the reservation had asked Lissa for help, and so Lissa organized a search party. The woman was discovered in a farmer’s garage, not far from the bar where she last was seen. She had climbed into a vehicle, found a key in the ignition, and turned it on, perhaps to stay warm. She died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Soon afterward, Lissa had founded a nonprofit, which she named Sahnish Scouts. Other families from tribes and cities across the West and Midwest began to contact her, many of them missing their sons or daughters. Though federal agencies collected no reliable statistics, it seemed likely, based on available data, that Native American women disappeared at higher rates than women in any other demographic. In February 2015, the Fargo Native American Commission hosted a forum on missing Indigenous women and invited Lissa to speak.

When I met Lissa, she had just begun to develop a public persona, but while she spoke openly about missing person cases, there remained an aspect of her work that most people never saw. In the time I spent with her, I would never hear her tell anyone else about the beware flyers, nor about the messages she traded with Sarah Creveling. Even with loyal volunteers, Lissa shared very little. She compartmentalized her relationships. Often, she would glare at me if I publicly referenced something she did not want others to know.

I learned to ask questions in private or in the company of only her children, whom she trusted more than anyone. I knew when she was withholding information from me as well, or waiting to tell me certain things. I listened carefully. Sometimes, she would answer a question with silence and, weeks later, pick it up again, as if no time had passed.

Her secrecy was in deference to her sources, many of whom were fearful. Lissa was in touch not only with victims’ relatives but also with the relatives of an expanding cast of perpetrators. One night, I was riding with Lissa when she received an unexpected call from the stepmother of an accomplice to KC’s murder. The woman had seen Lissa mentioned in an article about the case. She did not understand how her stepson could have done such a thing and sobbed for hours into the phone as Lissa tried to console her.

After I started spending time with Lissa, I found myself looking more often in car mirrors, memorizing license plates, glancing around to see if anyone was following.

People told things to Lissa they would not have told police. This was particularly true on the reservation, where there remained a deep distrust of outside law enforcement. Once, in the spring of 2014, an elder had called Lissa with a tip. He refused to share his tip over the phone and insisted on meeting Lissa in person, so they met at a gas station an hour north of Fargo.

“You know how Indians are,” Lissa later told me. “We’re going to sidestep what we’re really there for and go all the way around the bush and then come back to the point.” The elder finally told her that he had a nephew in Mandaree who drank and used meth. One night, when the nephew was drunk, he had confessed to his father that he had reburied a person’s body.

Lissa tried to contact the nephew, but he had deleted his Facebook account, and when his relatives asked about the body again, he denied every part of his story. Lissa began leaving notes for him at the Mandaree store; he never got in touch. She did not press it, but she began to take seriously the possibility that KC had been moved from his original burial site. Case investigators thought this was unlikely—James was far too lazy, they said—but Lissa had not ruled it out.

According to a document filed in advance of the trial, Suckow returned to the reservation two weeks after he murdered KC and told James he wanted to rebury the body. “Don’t sweat it,” James had said. Either James did not want to disturb the burial site, Lissa thought, or he had arranged for the body to be moved by someone else.

In the spring of 2015, on another trip to the reservation with Lissa, we stopped at the Mandaree store, where she met with a tribal member. The member had been among the first informants to speak with Steve Gutknecht, the Bureau of Criminal Investigations agent, in July 2012 regarding KC’s disappearance. He had worked with KC in the oil fields and, in his interview, suggested KC was buried in a cattle bone pile near Maheshu. Around the time KC disappeared, the informant had been driving by the shop late at night when he noticed a backhoe digging in a nearby field. Lissa had been trying to meet with the informant for months. I waited with Waylon and Micah in the car while they spoke, and when they were done, Lissa brought the informant—a short, nervous man—to greet us.

“You packing arms?” he asked.

“No,” Lissa said. “I’m a felon.”

Waylon pointed to an eagle feather dangling from the rearview mirror. “We’ve got this for protection,” he said. The informant scoffed. As we left Mandaree, Waylon shook his head. “These nontraditional Indians,” he complained. “They get scared when they see an eagle feather.”

I laughed, but the man’s fear made sense to me. While James was in custody, not everyone allegedly involved in his schemes had been arrested. There was still George Dennis, who had delivered KC’s body to the burial site; and Justin Beeson, who had watched the door of the shop while KC lay inside. Recently, it had emerged in court records that Ryan Olness, the Blackstone investor from Arizona, was at the shop on the day KC was murdered and had known about it.

And there was the hit man James solicited for other unsuccessful murders. When a portrait of this man, Todd Bates, appeared in the news, Lissa recognized him instantly. He was the man she had spotted watching from his car in the Maheshu lot on the day she went with Rick, Jill, and Jill’s husband. Lissa showed me the photograph she took that day alongside the portrait, and, indeed, the man appeared to be the same person.

I felt unsettled that so many men had participated in the murders and not one, in two years, had mentioned it to authorities. But strangely I did not feel afraid. I could not feel afraid with Lissa, whom I believe infected me with her confidence. It was not that she considered herself safe; it was that she considered herself invincible. I knew she did not have the same confidence in me. She insisted that my eyes were not wide enough, that I could not see what was happening around me.

After I started spending time with her, I found myself looking more often in car mirrors, memorizing license plates, glancing around to see if anyone was following. I wondered if Lissa was paranoid, her caution a residual effect of the years she spent evading social workers and police, but then something happened that made me sorry for doubting her. One evening, when we stopped in Bismarck for gas, Lissa spotted two white men in an SUV staring at us from across the road.

I saw the men and thought nothing of them, but as we prepared to leave, they came and parked behind us. They followed us closely for several minutes, and when at last I turned to look back at them, they fled. “You see!” Lissa said. “And you think I make this shit up.” I never suggested she made shit up, but I knew what she was getting at.

__________________________________

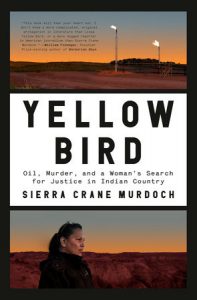

From Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country. Used with the permission of the publisher, Random House. Copyright © 2020 by Sierra Crane Murdoch.

Sierra Crane Murdoch

Sierra Crane Murdoch, a journalist based in the American West, has written for The Atlantic, The New Yorker online, Virginia Quarterly Review, Orion, and High Country News. She has held fellowships from Middlebury College and from the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley. She is a MacDowell Fellow.