On the Time the Iron Sheik Threatened to Kill Me

Brad Balukjian on Falling in Love with Professional Wrestling, Kayfabe, and Fact-Checking an Angry Childhood Hero

2005, Fayetteville, Georgia.

The Iron Sheik just threatened to kill me.

To be fair, he’s giving me choices: “I’ll shoot you with my .38 Magnum, stab you with my Bowie knife, or just break your fucking leg,” he spits, his voice coarse.

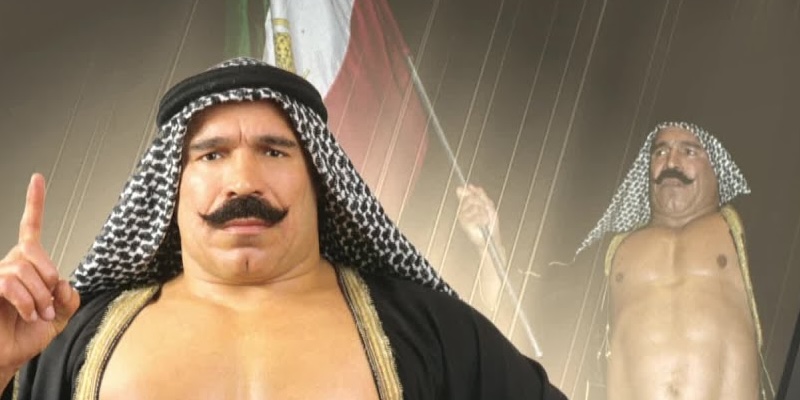

At age sixty-three, the ropes of muscle in his neck and shoulders remain thick. His head sinks into a cement-mixer chest, his handlebar mustache still meticulously curled but now flecked with gray. The very same man whose action figure I once smacked against Hulk Hogan in elaborate matches on my bedroom floor is now swaddled in front of me in a plaid blanket, the fabric concealing an eggplant colored left ankle and two poorly replaced knees. The ankle is so bad that he takes every step on the side of his foot to minimize the pain.

A Dallas Cowboys wool hat covers his iconic bald head, his scalp pocked with scars from years of cutting himself with razor blades during matches, a practice known as blading in the parlance of professional wrestling (they don’t use blood capsules). Toward the back of its lunar surface lies a particularly deep crevice, marking the spot where a crazed fan in South Africa hit him in the head with a blackjack.

“The people have to pay to see the head,” he is fond of saying. Outside of showering, his head is always covered with a hat or durag representing some sports team or wrestling event given to him by a promoter or fan. You never pay for clothes when you’re a household name.

Hailing from Tehran, Iran, he was the ultimate bad guy, or heel, marching to the ring waving a flag of Ayatollah Khomeini, shouting “Iran Number One!” and playing off every Middle Eastern stereotype at a time when such jingoism ran rampant.At the height of professional wrestling’s boom in the 1980s, the Iron Sheik was my hero. He appeared in Cyndi Lauper music videos, starred in Toyota commercials, and was literally a cartoon (part of the ensemble cast of Hulk Hogan’s Rock ‘n’ Wrestling). Hailing from Tehran, Iran, he was the ultimate bad guy, or heel, marching to the ring waving a flag of Ayatollah Khomeini, shouting “Iran Number One!” and playing off every Middle Eastern stereotype at a time when such jingoism ran rampant.

But few knew that he really was from Iran, born Hossein Khosrow Vaziri (he goes by “Khos”), and that his life before becoming the Iron Sheik was just as full of controversy. Even his birthday is a dispute—his passport says March 15 while his driver’s license says September 9; the small town where he was born, Damghan, didn’t keep reliable records.

Growing up before the country’s Islamic Revolution, Khos had only one dream—to be the greatest amateur wrestler Iran had ever seen. At age fourteen he went to a brothel to get the number “90” tattooed on his right forearm, representing the weight, in kilograms, of his hero, Olympic gold medalist wrestler Gholamreza Takhti.

He eschewed any carnal delights, dedicating himself to training and prayer. For forty consecutive Fridays he rode a bus two hours each way to worship at a Shia mosque. He enlisted in the Iranian army and, given his prowess on the wrestling mat, was recruited to be a bodyguard for Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s wife Farah.

But right now all of that is a distant memory as I stand in his living room facing the most surreal multiple-choice question of my young life: How do I want to die? At the hands of my hero, no less?

I scan the living room, which is tastefully decorated thanks to his wife of thirty years, Caryl. There are two couches and a plush chair located toward the center of the room, and in the adjoining dining room I spy a chandelier, china cabinet, and, on the wall, a framed wedding photo—Caryl with a short, mod, seventies hairstyle and Khos in his pre–Iron Sheik days, svelte, sans mustache, with a mane of thinning black hair.

I am positioned several paces away from Khos, and although he is as mobile as an anvil, I don’t feel particularly good about making a run for it.

My left hand tightens around my notebook while my right clenches a pencil. My heart thumps as I look down at the floor, not wanting to acknowledge my idol’s eyes. There have been plenty of tense moments over the past couple months—driving him to a roach motel to buy drugs, hearing him rant and scream at Caryl for no good reason—but death threats are new. My mission, to work with him on writing a book about his life, now seems compromised.

Apparently Iron Sheiks also don’t take kindly to fact-checking. Moments ago, following a trademark out-of-the-blue, pec-slapping, mustache-twirling rant about how he is the only wrestler to come out of the Middle East and become a star in the U.S., I had calmly stated, “Well, Khos, there was someone else. General Adnan from Iraq.”

The moment my words reached his eardrums, his dark brown eyes turned a shade darker. It’s a look that had become all too familiar. Not only had I contradicted the former World Wrestling Federation (WWF) champion, I had invoked the name of the country that had fought a bloody nine-year war against his native Iran.

I was right, of course, that General Adnan (real name: Adnan Alkaissy) is from Iraq; he had been a childhood friend of Saddam Hussein and played the role of evil henchman to Sgt. Slaughter during the Desert Storm war in 1991 (ironically, Khos played Slaughter’s other henchman under the name Colonel Mustafa, but I don’t dare pile on).

To Khos, I am unnecessarily putting him down, letting facts get in the way of a perfectly good promo.

Just as I am leaning toward the .38 Magnum for my fate (the quickest option), I look up and see some of the crimson starting to drain from his face, the adrenaline rush subsiding.

“Brad baba” (he calls everyone “baba”), “why do you say that? Why don’t you put me over?” His accent is thick and his English choppy, inspiring many imitations from fans and fellow wrestlers alike.

In the lexicon of “Kayfabe,” pronounced ˈkāˌfāb, putting someone over means allowing your opponent to win a match, or more generally, showing them support. (Kayfabe is the all-encompassing name given to wrestling’s bizarre and unique set of customs, language, and overall culture. The term’s origin is a mystery—some believe it to be bastardized Pig Latin for “fake.” Indeed, such manipulation of words created the foundation for the carny language that wrestlers use to communicate with each other, inverting words and adding syllables.)

In order for a wrestling match to work, you have to, well, work, which is Kayfabe for cooperating, and is the opposite of a shoot, which would be a legitimate fight. For the last thirty-three years, Khos has been working so well that his grip on reality has become somewhat tenuous. At the moment, I am shooting (but what about General Adnan?) when I should be working.

But it wasn’t always like this. A couple months prior, when I had arrived in this suburb of Atlanta to start work on his biography, Khos had greeted me at the airport with a big smile, flashing a set of gleaming, gap-ridden teeth and saying, “Excellent, Brad baba, we’re going to make million, million dollars together.”

So what went wrong?

*

Without a doubt, professional wrestling and I are unlikely bedfellows. A product of private schools and upper-middle-class rearing in the outskirts of Providence, Rhode Island (to be fair, everything in Rhode Island is technically in the outskirts of Providence), I shouldn’t be a fan of such lowbrow entertainment, such trash.

“You like that stuff?” they would ask. “How? It’s so fake!”

And that was my own parents talking.

But to timorous, scrawny, six-year-old me, wrestling was the ultimate outlet, a world where I could be strong and fearless, where I could let my bottled-up anger loose and still not hurt anyone because it was all done with a wink and a nod. When my mother saw me practicing the figure-four leglock on my younger sister, Lauren, she grew concerned and called my aunt.

“Don’t worry about it,” Aunt Rom replied, putting me forever in her debt. “Brad’s such a shy kid, it’s a good outlet for him!”

Watch any Balukjian home video from the 1980s and you will witness the product of Aunt Rom’s counsel. Buck-toothed and gangly, one minute I’m perched in the corner silently paging through the world atlas, and the next I’m in the face of the camera, finger-pointing, shouting to an imaginary opponent, “I’m the best, I’m the champion, you’ve got nothing!”

My dad’s irritated baritone undercuts my high-pitched rant—”Brad, I can’t see your sister!”—but this is no matter; I have morphed into Exciting Balukjian, my good guy or babyface persona, and have declared war on all the heels in the dressing room.

Social critic Roland Barthes once called wrestling “a spectacle of excess,” and for an insecure kid with headgear and a stutter, that excess gave me something to look forward to every Saturday morning when I plopped in front of the TV to watch Hulk Hogan, “Macho Man” Randy Savage, and the Iron Sheik grapple in sweaty make-believe.

The Iron Sheik, whose entire gimmick was predicated on xenophobia, was my favorite. I was drawn to him not because I was unpatriotic—I proudly pledged allegiance every day at Henry Barnard Elementary School—but because the Iron Sheik was the guy nobody cheered for (I was always about the underdogs), and he had a really cool handlebar mustache and curly-toed elf boots (these things matter when you’re six!).

While some of the other heels like “Rowdy” Roddy Piper or Jake “The Snake” Roberts got cheers for being cool antiheroes, the Iron Sheik was universally disliked. How could you cheer for a man whose tag-team partner, Nikolai Volkoff, demanded that the crowd stand and respect his singing of the Soviet national anthem at the height of the Cold War?

I was drawn to him not because I was unpatriotic—I proudly pledged allegiance every day at Henry Barnard Elementary School—but because the Iron Sheik was the guy nobody cheered for (I was always about the underdogs), and he had a really cool handlebar mustache and curly-toed elf boots (these things matter when you’re six!).Wrestling dominated my childhood and adolescence. A friend who won backstage passes invited me to meet a few wrestlers before a show at the Providence Civic Center, and Jake “The Snake” Roberts and Hillbilly Jim loomed like redwood trees as I watched them sign autographs. I marveled at my proximity to these men who until that moment seemed to only exist in the flattened realm of my TV screen. They were real, and yet they were still theatrical, Jake with his python-emblazoned neon-green tights and Jim with his overalls and beard the size of a porcupine.

In the seventh grade I hit an all-time low of social capital as classmates mocked my stutter and demonstrated the type of assholery that only seventh graders are capable of. But I never fought back, never stood up for myself; instead I went home, plugged in my wrestling VHS tapes, and escaped. My mom cried when I taped Saturday Night’s Main Event over one of her episodes of All My Children.

Whatever aggression wasn’t taken out through wrestling was channeled into my schoolwork. When final exams rolled around in high school, I posted a sign on my bedroom door that read “The War Room” and told my parents to hold any phone calls from my friends (by this time, I had some).

I staged study sessions that would make the most ascetic German tear up with pride, marathons of rewriting notes with such pressure that the paper felt like Braille. And when the last exam was done, it was back to the VCR to escape to the land of the bodyslam.

______________________________

Excerpted from The Six Pack: On the Open Road in Search of Wrestlemania by Brad Balukjian. Copyright © 2024. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.