On the Time Benjamin Franklin, American Show-Off, Jumped Naked Into the Thames

Vicki Valosik on Our Millennia Long Love-Hate Relationship With Getting in the Water

It was a fine early summer afternoon in England, and the port at Chelsea was just slipping out of sight when Benjamin Franklin—at the urging of his fellow passengers—kicked off his buckled shoes and tossed aside his heavy jacket. John Wygate, a fellow printer whom Franklin had taught to swim, had been regaling the gentlemen aboard the ferry with stories of Franklin’s fishlike agility in the water and the peculiar aquatic tricks he could perform.

They had spent the morning viewing taxidermied crocodiles and rattlesnakes at Don Saltero’s curiosities shop and weren’t ready for the day’s amusements to end, even as they headed back to Blackfriars. Franklin likely put on a good show of modesty, demurring at first to the group’s excited requests for a demonstration, but was no doubt secretly pleased as he undressed for his dip in the Thames—he loved both an audience and any excuse to get in the water.

With his short breeches, knee socks, and frilly-collared shirt folded safely away, leaving only his birthday suit, nineteen-year-old Franklin leapt off the edge of the boat. Some of the men’s hearts may have quickened at the thought of their own heavy, landlubber bodies plunging into the dark water; overboard was not a place most people in the eighteenth century went voluntarily. Despite the great amount of time spent on ships and ferries, swimming was a rare skill among men. Among women, it was unheard of—even suspect.

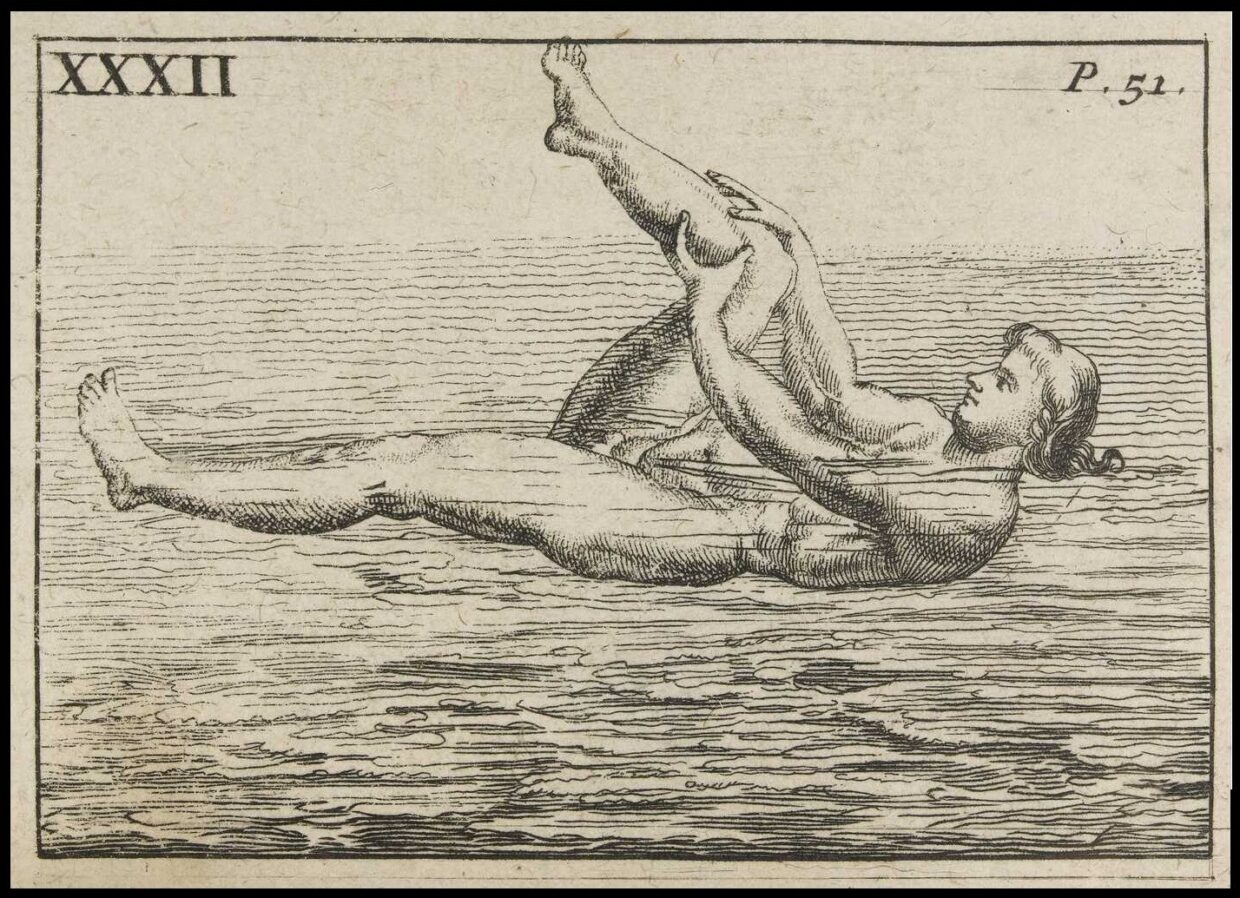

An illustration from Thévenot’s translation L’Art de nager demonstrating how to “boot oneself” in the water.

An illustration from Thévenot’s translation L’Art de nager demonstrating how to “boot oneself” in the water.

Franklin, however, was in his element—and it showed as he floated effortlessly on his back, bobbed like a spinning top with his knees held tightly to his chest, and dove under and above the surface like a porpoise. This future statesman and political philosopher, known in London as the “Water American,” was a proud practitioner of what would later be called “scientific swimming.”

He could float on his back and raise a leg straight in the air, mastlike—much as a modern-day synchronized (or artistic) swimmer would do. He could make a circle on the surface, his head remaining still in the center like the point on a compass as his legs rotated around it. He could swim on his back, arms free to ferry dry clothes or declarations and treaties high above the water. He could even swim on his belly with his wrists tied behind his back.

Franklin performed his aquatic feats that day in 1726 “both upon and under the water” all the way to Blackfriars, a distance of about three miles, and recalled that they “surpris’d and pleas’d those to whom they were novelties.” Franklin, who had harbored a love of swimming since his boyhood when he taught himself to swim in the Mill Pond near his family home in Boston, wrote in his autobiography that he learned these particular tricks from a book by a Frenchman named Melchisédech Thévenot: “I had from a child been ever delighted with this exercise, had studied and practis’d all Thévenot’s motions and positions, added some of my own, aiming at the graceful and easy as well as the useful.”

Despite the great amount of time spent on ships and ferries, swimming was a rare skill among men. Among women, it was unheard of.Although he credits Thévenot for his sleek aquatic moves, they actually originated with an Englishman and Cambridge theologian named Everard Digby, who, in 1587, authored England’s first swimming manual of the modern era. Digby’s book, De Arte Natandi (The Art of Swimming), contained descriptions and woodblock illustrations of a variety of useful and aesthetic, as well as downright odd, stunts one could do in the water, such as the “ringing the bells” turn, “carrying the left leg in the right hand,” keeping “one foot at liberty,” “the leap of the goat,” and even paring one’s toenails with a knife while floating.

In providing instructions for these aquatic “refinements,” Digby hoped to revive swimming—a once revered skill that had all but died out during Europe’s Dark Ages—and elevate it from a crude, mechanical function of the hands and feet to an artful science. He promised readers that through frequent practice of the precepts laid out in his little tract, they “may attain to the habit of Swimming perfectly.”

Digby’s De Arte Natandi was translated within a few years from its original Latin into English by a man named Middleton, but it wouldn’t reach a wide audience until Thévenot translated the text to French in 1696, adding a lengthy introduction and improved illustrations. Thévenot’s translation, which was published as L’Art de Nager and makes only a passing mention in the introduction of Digby—referring to him as “an English Man wherof I have here made some use”—was then translated into German, Spanish, Italian, and again to English. As Thévenot was a scientist well-known among Enlightenment-era thinkers, it was the version with his name splashed across the cover that Franklin and others would discover—while Digby would be largely forgotten.

And although Digby wouldn’t live to see it, his book, helped along by the Renaissance-inspired embrace of classical ideas, would indeed help spur the aquatic revival he dreamed of. His repertoire of movements—and the techniques he used to achieve them—would be studied and practiced by science-minded gentlemen swimmers like Franklin, later expanded and performed by aquatic artists of vaudeville stages, and, eventually, codified and elevated by female athletes into the competitive sport of synchronized swimming—which was christened as an Olympic event almost exactly four centuries after Digby’s book was first published.

*

As a passionate and skilled swimmer born on the cusp of the modern era, Digby was a century or two ahead of his time—or, one could say—a millennium behind. In ancient Greece, swimming was considered a skill as fundamental as reading, with Plato using the phrase “unlettered and unable to swim” as shorthand for an uneducated person. The Romans were even more famous for their celebration of all things aquatic. On any given day, men and boys in the Roman capital could be found splashing in the sea or the Tiber River; women swam too but mostly in private bathhouses.

Every town across the Roman world, no matter how small, had to have at least one thermae, public heated baths that served both hygienic and hedonistic purposes, with wine flowing and orgies stretching through the night as well-to-do Romans soaked and socialized. In many towns, larger baths, or natatoria, were purpose built for the more serious pursuit of swimming.

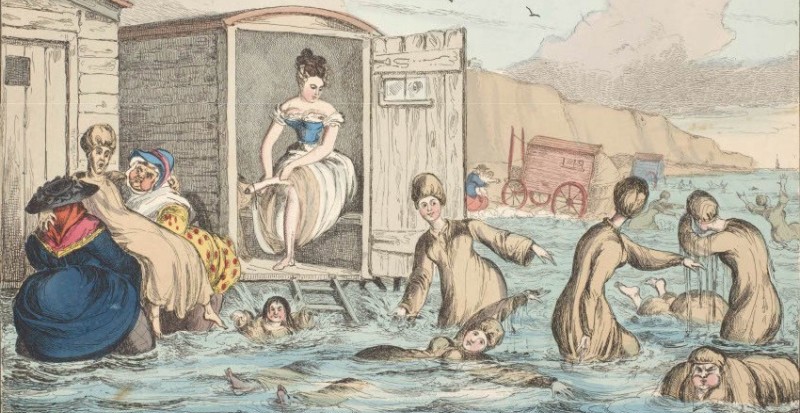

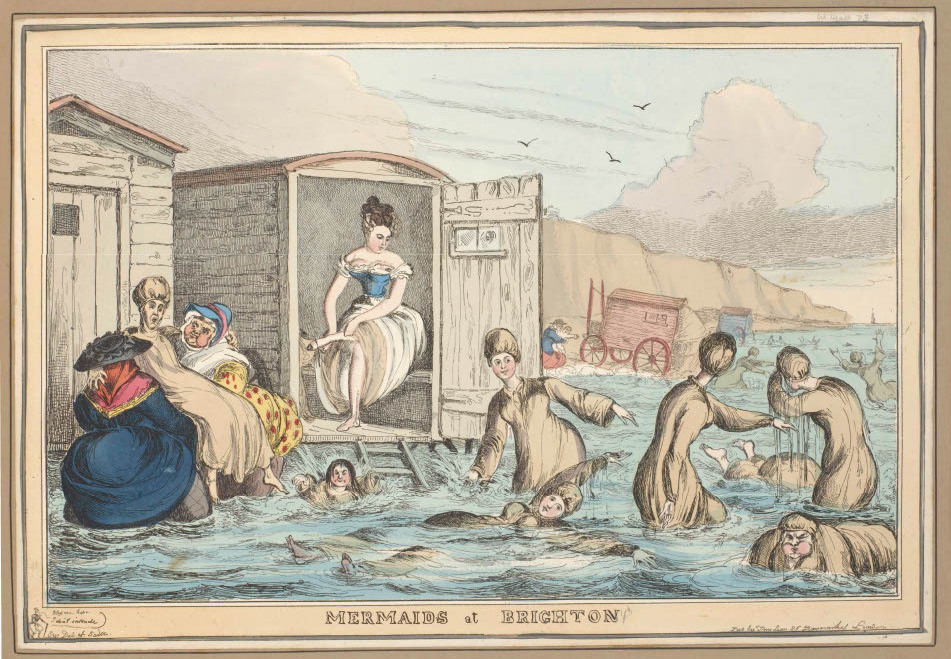

How gentlemen learned to swim in 1845. From Captain Stevens’ System of Swimming; The Only Rules for a Quick Initiation in the Same. 2nd ed. 1845 (Courtesy of Google Books)

How gentlemen learned to swim in 1845. From Captain Stevens’ System of Swimming; The Only Rules for a Quick Initiation in the Same. 2nd ed. 1845 (Courtesy of Google Books)

Even when they weren’t in the water, the Romans surrounded themselves with it, beautifying their urban centers with ornate fountains and waterscapes fed by complex aqueduct systems. On holidays, inland residents flocked to coastal resort towns like Antium, Baiae, and Naples to soak in the ocean vistas. Romans found tranquility in the sights, sounds, and smells of the sea—after all, Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, was formed from the froth of its waves. Just as Poseidon had ruled the seas for the Greeks, Neptune commanded Rome’s waters, winds, and storms, while lakes, rivers, and springs were populated with lesser deities.

Emperors, the mortals at the helm of the mighty Roman empire, demonstrated their power through water as well, particularly through their ability to engineer this precious resource for use in lavish—and often gruesome—spectacles. Among the grisliest were naumachia, waterborne gladiator games of mortal combat in which slaves and prisoners were set aboard small ships and forced to fight one another to the death in naval battles staged in lakes and flooded amphitheaters. When the Flavian Amphitheater, now known as the Colosseum, was completed, Emperor Titus celebrated in 80 CE by filling its basin with water and hosting naumachia and other aquatic entertainments, including an enactment of Leander’s mythological swim to his lover, Hero.

In another act, described by historian Kathleen Coleman as “an ancient equivalent of synchronized swimming,” a large group of women dove, cavorted, and created shapes in the water. Playing the role of water nymphs, or Nereids, the women likely swam nude, their bodies illuminated by torchlight as they formed the outlines of a star, trident, and ship. Similar but smaller aquatic productions called “Thetis-mimes” were popular across the Empire. Orchestra basins of amphitheaters, such as the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, were waterproofed and filled to create pools where women would swim and pantomime mythological stories.

Instead of controlling water and harnessing it for their enjoyment and social utility, as their ancestors had done, humans came to fear it.However, as Christian beliefs and practices began taking hold, there was an intentional renunciation of the pagan practices of Rome. Early church fathers like John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople during the fourth century, sought to discredit the Thetis-mime shows, maligning the performers as prostitutes, and warning parishioners that going to see them would lead directly to “shipwreck of the soul.”

Thermae and pools were viewed as playgrounds for sinners and wastrels, glaring symbols of Roman indulgence and excess, while water increasingly came to be associated with pleasures of the flesh—the very pleasures Christians were supposed to deny themselves in this life if they hoped to achieve paradise in the next. Even before the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, many of its pagan practices were banned, and over the years its theaters, pools, and aqueducts were either destroyed or left to fall into disrepair.

As invading tribes took over former Roman territories, they brought vastly different views of the water. Whereas Greco-Roman mythology populated the earth’s waters with divine characters, the seas and rivers of northern cultures were teeming with monsters rather than gods. Nordic fishermen and sailors were at the mercy of Kraken, a colossal, ship-sinking cephalopod; Jörmungandr, a venomous sea serpent; and Nikr, a seafaring horse that appeared tame, only to lure human prey to their watery deaths. To these newcomers, beachy shorelines were not arenas for reflection or frolic, but represented the edge of safety and the very end of the known world, beyond which lay a “witch’s brew” of dangers.

By Europe’s Middle Ages, Rome’s aquatic paradise was a distant memory. Churchgoers were reminded that God had used water to destroy the earth, while the few Bible verses that mention swimming were interpreted as signs of man’s helplessness and drowning as a metaphor for sin. Superstition, rather than science, dictated their relationship with the natural world—so much so that even the simple act of floating could be taken as a sign of witchcraft.

Eventually, getting wet, other than for baptism, was to be avoided, as water was blamed for weakening the body and spreading disease and plagues. Instead of controlling water and harnessing it for their enjoyment and social utility, as their ancestors had done, humans came to fear it, associating it not with health and pleasure but with death, condemnation, and the terrifying unknown.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Swimming Pretty: The Untold Story of Women in Water by Vicki Valosik. Copyright © 2024 by Vicki Valosik. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.