On the Tenacity and Bravery of a Great Journalist

Marie Colvin, Reporting from East Timor

By early September 1999, Marie Colvin was on to a new story. East Timor had long been known as a dangerous place for journalists. Back in 1975, Indonesian soldiers, who were invading the territory at the end of Portuguese colonial rule, had killed five journalists working for Australian television. It was no accident: they wanted to ensure there were no witnesses to their brutal campaign to seize control of East Timor against the will of its people. In the two decades that followed, up to one-third of the Timorese population was killed or died of hunger and disease, and their plight became a cause célèbre among human rights activists. Britain and the United States saw the Indonesian dictator Suharto as a stable force in the region, and East Timor was largely ignored until 1998, when Suharto stepped down and a new Indonesian government agreed that the United Nations should organize a ballot on independence for the territory. Polling day was August 30, 1999.

It was clear that the Timorese would vote for independence, but not that Indonesia would cede control without a fight. Others on the paper predicted mayhem and thought it too dangerous, but Marie was deter- mined to go. Violence surged in the run-up to the poll. Wild-haired militiamen terrorized Timorese civilians and, on one occasion, used swords, machetes, and iron bars to attack a car full of journalists while Indonesian police looked on. In April, some 200 Timorese civilians were killed in the priest’s house next to the Catholic church in Liquiçá. Blood ran down the walls after the militia shot through the roof to murder terrified people hiding under the eaves. The massacre had a horrible resonance for the UN mission overseeing the referendum, reminding them of the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, when tens of thousands were slaughtered in churches where they had taken refuge while UN peacekeepers failed to come to their rescue.

Polling day was emotional: music blared from the churches, everyone dressed in their best, and more than 98 percent voted, some queuing for hours in the hot sun. Even before the result was announced, militias attacked pro-independence supporters outside the compound of the UN Mission in East Timor, UNAMET, in the East Timorese capital, Dili. A hotel where journalists were staying was ransacked, and a BBC correspondent was nearly killed when militiamen kicked his head and hit him with a rifle butt. After that, most editors pulled out their correspondents. The Indonesian strategy was clear: whatever the outcome of the referendum, the government planned to use the militias to intimidate and threaten all foreigners—journalists, aid workers, election observers, and the United Nations—until they left.

Marie and Maggie O’Kane, whom she knew from Baghdad and who was now writing for The Guardian, were on the last plane into Dili. They checked into the Hotel Turismo. “Where is everybody?” Marie asked two Dutch journalists, Minka Nijhuis, who wrote for a Dutch newspaper, and Irena Cristalis, who was filing for the BBC. Both had been to East Timor several times and knew the story well. They explained that only a couple of dozen journalists remained. “But the story’s only just beginning,” said Marie. She took a room with a balcony from which she could see the Red Cross compound, where a thousand terrified Timorese who had taken refuge were being attacked. A soldier pointed his assault rifle at a woman, while other women were kicked or hit with rifle butts. Militiamen roamed the courtyard, shouting and firing in the air. The Red Cross workers were powerless.

After about half an hour, some soldiers and militiamen drove the aid workers to the airport, while others looted the refugees’ possessions. They separated out the women and children before marching the men away, as the police again looked on passively. Soldiers and militia were banging on the doors of the journalists’ rooms at the Turismo. No one answered, but it was clear they couldn’t stay. The Australian ambassador came to the rescue, loading the journalists into diplomatic vehicles. There was no time to collect their belongings. “What do you want, your life or your clothes?” he yelled at a reporter who tried to get a bag. Marie managed to grab her computer and satellite phone. The journalists were driven to the UNAMET compound, two miles away.

They were not the only ones taking refuge there; chased by militiamen, desperate Timorese men and women had scaled the walls, braving razor wire coiled on top—several threw their babies over, and at least 50 people were treated for gashes. The next day, more refugees arrived, including an organized column of 800 led by an elfin nun called Sister Esmeralda. Holding her Bible, she had walked up to a unit of Indonesian army and militia, who, she said, had made a corridor like the Red Sea parting for Moses. UNAMET was located in the Teachers’ College, surrounded by hills and with a swamp in front and a single road out. It was indefensible, and the mission was unarmed. UN security officers felt naked—how could they protect themselves let alone the refugees? But some thought it was better that way, because even the Indonesian military might hesitate before attacking unarmed foreigners.

No activist, Marie Colvin nonetheless saw a clear choice between right and wrong in East Timor.

Inside the compound, pandemonium reigned. Several local UN staff from outlying areas had been murdered, so the rest, including their families, had arrived along with the internationals. UN officials knew they couldn’t abandon local staff as they had in Rwanda, but they were short on food, and fuel for the water pump was running low. More than 2,000 terrified people were cooking over small fires, sleeping on the ground, and using the increasingly insanitary toilets.

The head of the UN mission, Ian Martin, was holed up in his office talking on the phone to the Indonesian defense minister, the UN secretary-general, and world leaders, trying to find a way to pressure the Indonesians into stopping the violence, which they were clearly orchestrating. For the UN public information officer, Brian Kelly, the arrival of 26 journalists was a mixed blessing. “I more than welcomed the presence of Marie because she was a genuine professional,” he recalls. “But a lot of the ‘journalists’ in that batch were single-issue activists using journalistic reasons for gaining access in Timor. They were demanding and excited and very difficult to handle.”

They were also highly critical of the United Nations, which they felt had been unprepared for the chaos following the referendum and was not doing enough to save the people of East Timor. Some UN staff, desperate to leave before they were slaughtered along with everyone else, saw Marie as a troublemaker because she would say loudly that if they left, the refugees would be massacred and the United Nations would have blood on its hands. No activist, Marie nonetheless saw a clear choice between right and wrong in East Timor.

Two days after Marie reached the compound, Indonesian soldiers allowed militiamen to ambush a UN convoy they were supposedly escorting on a mission to retrieve supplies from the port. Every night, gunfire sounded just outside the compound. One evening, Marie and Brian were chatting outside when a bullet, probably a stray, swished through a tree and hit a UN car about ten yards away. “Heavy leaves here,” Brian said laconically. The press officers were receiving constant calls from media across the globe on a satellite phone left by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Brian asked the reporters to take some of the calls. “They could talk emotionally and dramatize it more than was permissible to a UN spokesman,” he explains. “It drew more attention to what was going on and indirectly kept up the pressure on the UN as well as the Indonesians.”

Eight thousand miles away in London, Sean grew used to hearing Marie’s voice on BBC Radio 4. He heard her say that militiamen were about to break into the compound. “I thought they were coming in, and everyone was going to be slaughtered, and Marie wouldn’t stand a chance,” he recalls. “By the time I managed to speak to her myself, the militia had pulled back, and the immediate danger seemed to have passed.” He didn’t mind her broadcasting, but he suggested that she send him a 500-word file every day so they could compile a piece for Sunday even if communications had gone down by then. She sent nothing.

With supplies alarmingly low, and unable to guarantee the security of UN staff, Ian Martin recommended to the UN secretary-general that they evacuate. After days of negotiation, he had an agreement from the Indonesians that local Timorese staff could go, too, and from the government in Canberra that they would be allowed to enter Australia. A whisper went through the refugees in the compound: the United Nations is going to abandon us. Thinking it would be safer than staying in the compound, which would undoubtedly be overrun the moment the UN left, some slipped away into the hills, where a guerrilla force was gathering. Gunfire erupted as they escaped, and some were shot dead.

Marie walked through the compound giving the children yellow tennis balls left by a departing Australian delegation. Everyone was filthy and exhausted, but Marie, Minka, and Irena were feeling a bit better because they had broken open a suitcase left by Portuguese election observers and looted clean clothes and snack bars.

Marie and Irena decided to slip out of the compound early to see what was going on and try to retrieve some belongings from the Hotel Turismo. So as not to look like journalists, they took nothing with them, not even notebooks or cameras. A militiaman with a machete ran a finger across his throat to warn them what might happen if they didn’t turn back, but at that moment, a soldier pulled up in a truck and, in surprisingly good English, invited them to his office, a small, dilapidated building with an old sofa and chairs round a wooden coffee table. Lieutenant Dendi Suryadi turned out to be, in Marie’s words, “articulate and professional.” He served them noodles and an omelette, the first hot meal they had eaten for days, and talked of his desire to go to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. They asked him to drive them through Dili to the Turismo.

THE SUNDAY TIMES, DILI, SEPTEMBER 12 , 1999

It was an apocalyptic vision. Hundreds of militia roamed the streets, some walking, some riding up to three on a motorcycle with one carrying looted goods, the second an assault rifle, the third driving. It was a frenzy of looting. The post office was still burning, but most of the other buildings were burnt-out skeletons. The lieutenant drove grimly. Gunfire sounded nearby. There were no civilians or cars on the streets. It was as if the barbarians had taken over. One motor cycle passed us, the militiaman on the back waving his pistol at us and smiling maniacally, showing no fear of the army vehicle or its occupants.

At the Turismo, things got even more surreal—the militia had looted Marie’s La Perla bra and silk panties but had left her flak jacket. Lieutenant Suryadi insisted on driving them on what Irena called a sightseeing tour of the war zone. “We came to win the hearts and minds of the people,” he said. “I think we failed.” They watched militiamen torch a building. “Look carefully,” said Suryadi. “It’s important that you remember this.” By pure chance, the two journalists had come across an Indonesian officer who wanted journalists to see the terror his comrades were inflicting on the Timorese.

Back in the compound, Ian Martin gave a press conference, announcing that the UN staff, international and national, would evacuate. Any journalists who stayed would have to leave the compound. Marie suggested to Irena and Minka that they grab some food and set themselves up in a small house nearby. For protection, they would borrow a sporadically vicious black-and-tan dog who belonged to one of the refugees. As they walked to the gates to take a look outside, a couple of militiamen came by on a motorbike, grenades in hands. The UN guards shooed the three of them back to the compound. That was the end of that idea. It would not be possible to stay elsewhere.

Refugees were crying and praying, singing hymns, and reading the Bible. Marie allowed some to use her satellite phone to call their relatives overseas or in West Timor. Many wept, convinced this would be their last communication before they were killed. Sister Esmeralda shouted at the UN staff: “Now you leave us to die like dogs. We want to die like people!” She called her mother superior in Rome on Marie’s sat phone. “In twelve hours we will all be killed,” she said. The atmosphere was febrile. UN staff huddled, dismayed at the turn of events. They had come to East Timor to protect the people, and now they were abandoning them. A group of reporters went to see Ian Martin to protest the plan to evacuate, while a petition circulated for UN staff to sign if they wanted to stay on an individual basis. “Well, there goes a hot bath,” Brian Kelly thought, as he got out his pen. The evacuation was delayed by 24 hours. Most of the journalists, including Maggie O’Kane, had already left.

Everyone was hungry, tired, and on edge, talking endlessly about the risks of staying—would they starve, or be killed? Marie shrugged. “Forget it, I’m not leaving. This is the biggest story in the world,” she said to Irena and Minka. “She was very focused,” Irena remembers.

Marie called her friend, Jane Wellesley, to talk over her decision, but there was no doubt. “She was determined to stay,” Jane recalls. Marie knew it could be a fateful choice. “She called me to say goodbye, as she was likely to be killed,” Cat remembers. Later, she explained her thinking. “I just couldn’t leave. We’d been living with these people for four or five days, sleeping next to them, getting rice from them,” Marie told Denise Leith. “In a way it was a hard decision, because you had to think, I could die here. But equally I just didn’t feel I could live with myself if I left. It was morally wrong, the idea that we would walk out, say good-bye and all those people knew they were going to be killed. It was not a decision I could have made the other way.”

_________________________________

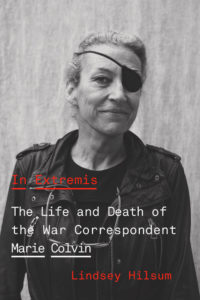

Excerpted from IN EXTREMIS: The Life and Death of War Correspondent Marie Colvin by Lindsey Hilsum. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on November 6th 2018. Copyright © 2018 by Lindsey Hilsum. All rights reserved.

Lindsey Hilsum

Lindsey Hilsum is the International Editor for Channel 4 News in England. She has covered many of the major conflicts and international events of the last twenty-five years, including the wars in Syria, Ukraine, Iraq and Kosovo; the Arab Spring; and the genocide in Rwanda. Her writing has appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Guardian, and Granta. Her first book, Sandstorm: Libya in the Time of Revolution was short-listed for the 2012 Guardian First Book Award. In Extremis is out now.