On the Spiritual and Historical Significance of “Divine Footprints”

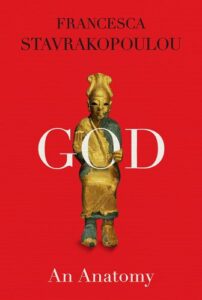

Francesca Stavrakopoulou Looks Closely at Religious Texts

A little over forty miles north-west of Aleppo, in northern Syria, set high above a valley, there lie the remains of a gateway to heaven: an ancient temple, the meeting place of the heavenly and earthly planes. A colossal carved lion, its teeth and claws bared, guards the approach. Surrounded by walls of black basalt, its floor paved with pale flagstones, the temple is the dwelling place of a long-lost deity, worshipped by the Syro-Hittites—close cultural cousins of the ancient Israelites and Judahites. Partially destroyed in the eighth century BCE, and devastated again in a Turkish airstrike in 2018, this temple at ‘Ain Dara is the closest we can come to the temple that stood in Jerusalem at the same time. Its structure and iconography map so precisely onto the biblical description of Solomon’s temple, it is as though they shared the same divine blueprint.

When I visited the temple in 2010, shortly before the war in Syria began, wild summer flowers dotted the grass at the temple’s edges, dappling the feet of guardian beings and lions lining the base of its now broken walls. I took off my shoes and walked barefoot up the warm, shallow steps to the entrance of the temple’s outer courtyard. And then I saw them: two giant footprints, each about a meter in length, carved into the limestone threshold; neatly paired, they were pointing into the temple. The toes and balls of each footprint were softly, deeply rounded, as though they had been pressed firmly into wet sand. I stepped into these enormous, yet delicate feet. They dwarfed my own. I was standing in the bare footsteps of a god. As I looked ahead of me, I could see the vastness of the deity’s stride into the temple: the left foot had been imprinted again a few meters inside the temple, this time on the entrance to the vestibule; ten meters or so beyond that was the right footprint, inside the holy of holies—the innermost sanctum, where the deity dwelt. The god had arrived home, and I was there to witness it.

This was the grand residence of a deity whose precise identity has long since been forgotten. But although this god would fade from view, their bodily presence was clearly marked by those giant footprints, traveling in just one direction: inside. There were no exiting footprints; no indication that the deity had left the temple. Rather, the footprints signaled the permanent presence of the god within. It is this sense of material presence that lies at the heart of ancient ideas about deities. The perceived reality of the gods was bound up with the notion that for anything or anyone to exist—and persist—is to be present and placed in some tangible form. It is to be engaged with and within the physical world. The footprints at ‘Ain Dara communicated precisely this sense of placement. They marked the exact place of the deity within the world of humans. At this spot, where the heavenly and earthly realms met, the god was manifest and accessible to worshippers. The deity took on a social life.

The power of the footprint to communicate complex ideas about social presence says as much about what it is to be human as it does about what it is to be a god. When we see footprints, we recognize them as material traces of being; a frozen moment of movement or stillness; a memorial—however fleeting—to a reality by which we configure ourselves in the world and with those around us. Footprints capture something of the extraordinary and the familiar about human life—the orchestrated and haphazard, the durable and flimsy. A toddler’s excited footsteps imprinted in sand or snow. Celebrity shoe-prints set in concrete on Hollywood Boulevard. Muddy shoes accidentally tracked across a kitchen floor.

The footprints of a group of Australopithecus afarensis, some of our earliest bipedal hominid ancestors, solidified in volcanic ash, three and a half million years ago, in Laetoli, northern Tanzania. The famous dusty bootprint of Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon. A footprint isn’t simply a trace or a representation of the foot. It is a material memory of its owner treading upon the surface on which the print appears, conjuring the presence of the whole body—the whole person. Our feet are not simply the pedestals on which we stand, or the motors by which we move, but the foundations of our presence in the world.

The impressions made by our feet have imprinted themselves into the religious cultures we have created. The footprints of gods and other extraordinary beings are celebrated and venerated all over the globe: divine or mystical beings are said to have left their footprints in rock art across Scandinavian and British sites of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. On an island sacred to the ancient Inca in Lake Titicaca, separating Bolivia from Peru, the footsteps of the sun god Inti are displayed. In southern Botswana, the giant hunter Matsieng left his footprints in wet earth around a waterhole. The extent to which the footprint appears in the ritual settings of human communities across time and space is remarkable.

Some of the earliest examples of divine footprints derive from the ancient sanctuaries of deities who once traveled the lands bordering the Mediterranean. According to Herodotus, the enormous footprint of Heracles could be seen in a rock by a river in Scythia—a print Lucian mockingly claimed to be bigger than the footprint of the god Dionysus, next to it. The Egyptian goddess Isis left impressions of her feet across the Graeco-Roman world: at Maroneia, in Greece, for example, her supersized prints appear alongside those of one of her consorts, Serapis. This divine couple is also invoked in a first-century BCE inscription upon a marble slab in Thessaloniki, beneath which the goddess has approvingly left her footprints.

Such is the power of divine footprints that they often became sites of competing religious claims. Most famous, perhaps, is the depression in rock akin to an enormous footprint on Sri Pada, a high peak in south-central Sri Lanka. For Tamil Hindus, it is the print of Shiva, left as he danced creation into existence; for Buddhists, the footprint belongs to Gautama Buddha, who pressed his foot into a sapphire beneath the rock; for Muslims, it is the print left by Adam as he trod on the mountain following his expulsion from Eden; for Christians, it is the footprint of Saint Thomas, who is claimed to have brought Christianity to the region. Jerusalem, too, has its share of contested holy footprints. As he ascended to heaven, Muhammad is said to have left a single footprint upon the exposed spur of bedrock enshrined beneath the Dome of the Rock, in Jerusalem.

But for Christian pilgrims and Crusaders of the medieval period, the footprint on this sacred rock belonged to Jesus, whose foot is also said to be imprinted on the Mount of Olives, where it has been venerated since at least the fifth century CE. Whether the work of geological erosion, local folklore or ritual art, each of these footprints communicates something of both the earthiness and otherworldliness of a divine or holy being.

In the Bible, God’s feet are crucial to his social existence—fundamental to his very being—and so they are the bodily features by which he often renders himself evident in the world.As my own feet rested in the footprints of an ancient deity in Syria, I better understood why the biblical God is so frequently concerned with the placement of his feet—and why we find his footprints all over the Bible and the landscapes its texts describe. In Genesis, Adam and Eve hear Yahweh’s footsteps approaching as he walks in the Garden of Eden; later in the same book, Abraham sees Yahweh standing with two other divine beings beneath a group of sacred trees, and subsequently goes for a walk with him. Soon after, Abraham’s grandson, Jacob, encounters Yahweh standing next to him in a sacred space at Bethel. In the book of Exodus, Moses meets God several times. When he first sees Yahweh in his corporeal form, the deity is standing on a magical rock in the wilderness. Later, when Moses ascends Mount Sinai with a group of tribal elders, God is seen again—along with a stunning close-up of the heavenly floor on which his feet rest:

Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel went up, and they saw the God of Israel. And under his feet there was something like a brick pavement of lapis lazuli, like the very heavens for clarity.

When the biblical story moves to Jerusalem, God’s feet are there, too. This time, they are surrounded by the fragrant trees of an Eden-like temple garden, which, Yahweh says, “glorify where my feet rest.” “This is the place for the soles of my feet, where I will reside among the people of Israel forever,” he declares of his temple in the city. It is the place to which generations of his worshippers would flock to encounter the presence of the divine.

In the Bible, God’s feet are crucial to his social existence—fundamental to his very being—and so they are the bodily features by which he often renders himself evident in the world. The force of his feet splits mountains. They shake the earth as he strides out from the desert. They crush the bodies of his enemies. They transform dust and dirt into holy ground. Like indelible tracks worn into the earth along ancient pathways, the precise locations at which Yahweh plants his feet impact the landscape: his sure-footed presence in the earthly realm transforms a piece of ground into a place, and a place into sacred space.

__________________________________

From God: An Anatomy by Francesca Stavrakopoulou. Copyright © 2021 by Francesca Stavrakopoulou. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.