On the Similarities Between Writing and Turning Oneself Into a Werewolf

Douglas Kearney Isn’t Afraid to Lose Control

We must begin with an understanding.

This lecture is about writing and werewolf practice.

In writing “writing and werewolf practice,” I do not speak in figures. No like or as haunts, invisibly, the phrase, grinning.

Writing’s no proxy, here, for a werewolf practice; neither do I aspire to write my way toward something werewolf-like.

So, while I will talk about writing, mostly I will discuss years of desire to be a werewolf.

It’s best I set down that before poetry I was committed to a werewolf métier. I’ve tried to recollect my introduction to the subject. This has proven fruitless, and I resist the urge to speculate for fear that I’d invent something too apt for this lecture. Better I say I can’t recall not knowing about werewolves and, simultaneously, being drawn to them. In werewolves, I do not see kin: I know I am not one. I see a goal of sorts.

To this end, before I’d turned ten, I worked out a regimen of exercises from cinematic werewolf metamorphosis scenes. The idea was to condition my body, for to prepare and, if I’m honest, activate my own transformation.

When I dream, sometimes I’ve dreamt myself a werewolf or some other shapeshifter.

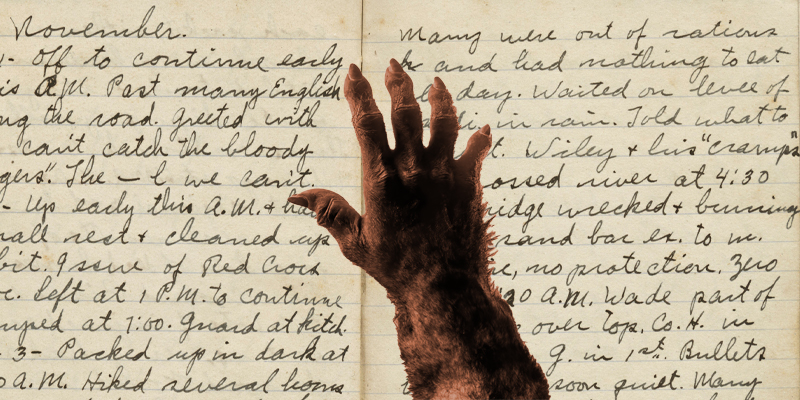

Stretches to accommodate a wolf/person anatomy, meditative sensory reallocation to facilitate my new perceptual enhancements, vigorous trials of focus… It remains true that I hope flexing my hand until the palm is convex while curling my fingers into hooked right angles will produce claws. It’s more than a tensorial curve, but a pushing you must picture. Conjure a knuckle there you’ve forgotten.

When I dream, sometimes I’ve dreamt myself a werewolf or some other shapeshifter. Only, that’s not why I’m talking about my dreams right now.

In some dreams, I am capable of something not quite flight, but if I jump, then rotate my arms just so, against gravity’s pull, I suppose, I can forestall alighting, extending the leap’s distance, remaining aloft in hung time. I’ve done this, again and again, such that I know how to manage it in different dreams. What’s more, walking around awake or, here, typing as I am and seated, I remember the feeling in my muscles, can remember it as sharply as I recall doing the Shoot, strapping tight Velcro shoes, tearing open Fun Dip with my teeth.

The memory, the sensation of it, seems tied to place and context. I cannot do a backflip except underwater. But I know the sensation and how to achieve it even when I haven’t been submerged for more than a year. Even here in this flimsy air, my body remembers, pieces together what it’s done.

While stretching my hands into claws, I hunt my memory. Have I ever felt talons grow from my fingertips? Do I know the twinge of lupine hair breaking my burning, blossoming skin? How does the paradigm of meaning-making shift when I find I can smell more keenly than I can see? In all these years, have I come closer to knowing?

You might suggest I use writing to account for these questions. Documenting my thoughts about them in a field journal—“May 26: I think I smelled a pig at one mile today.” Nope. I’ve no werewolf archive. There are a few poems, sure; yet they skin the lycanthrope to cover and do some other thing. Those poems, they are not telling you what I am telling you: that I have meant to be a werewolf, and that this has been, I’m afraid, a quiet, lifelong ambition, a discipline I’ve maintained longer and to less purpose, it would seem, than nearly all else.

Still, “less purpose” does not mean no purpose at all. Writing this lecture dogged me to ponder the why of it. Many familiar with my poems could observe that popular associations between werewolves and violence may find chime with my work’s steady study of brutality. As is true for many people, violence has been my grim companion. Systemic and personal. With me as subject and object. The werewolf’s ability to savage often comes bound to an act of violence visited upon them. An animal attack. A curse. A punishment.

The werewolf’s ability to savage often comes bound to an act of violence visited upon them.

Most of my life, I’ve found violence inextricable from control. You’ve a temper you couldn’t manage. You force someone do something they don’t want to do. You lost in one place and will damn sure “win” in another. Control, absent and present, knotted with violence.

People use the werewolf, my wife—a lifelong horror fiction enthusiast and writer—reminds me, to narrate about control and the social toll of losing it. It should not surprise anyone familiar with my work that control—formal, rhetorical, prosodic, compositional, thematic, performative, and social—are central concerns.

But is this relationship to control why I have wanted to become a werewolf?

In Shapeshifters: A History, author John B. Kachuba writes:

The werewolf is probably the most well-known shapeshifter and is the quintessential example of what can go wrong when that animal nature takes control. Its popularity and attraction may say something about our own latent desires to be free of the shackles of morality and social mores and to run naked through the night-time woods, howling at the Moon.

Stephen King, in his unofficial dissertation on horror, Danse Macabre, has it:

What we’re talking about here, at its most basic level, is the old conflict between id and superego, the free will to do evil or to deny it…or in Stevenson’s own terms, the conflict between mortification and gratification. This old struggle is the cornerstone of Christianity.

The Stevenson he’s speaking on is Robert Louis, author of what King considers the foundational werewolf text of popular imagination, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). What I find interesting about both Kachuba and King’s assessments of werewolfery is a suggestion that by turning into a wolf or wolflike creature, one escapes societal controls. This seems mighty—something or other. Consider Gévaudan, a now gone southern region of France, which from 1764–1767 was beset by a beast many cried was werewolf. Slaughtered about one hundred locals, several savagely decapitated. In answer, King Louis XV sent his royal gunbearer who, with his nephew, slew a 130 lb. wolf who fit a fuzzy description. A couple of months later, the killings continued. Whoops. Karl Hans-Taake, who wrote The Gévaudan Tragedy: The Disastrous Campaign of a Deported ‘Beast,’ notes that “from 1764 to 1767, more than a hundred wolves were killed in Gévaudan. Half a dozen of these wolves were thought to be the Beast.

When I dream of revenge, I’m not proud to say, I don’t care for ambiguity about my identity.

What I mean to mean with this is that, if one were to become a wolf, free themselves of some shackles, and do evil, there would soon come mobs killing anything what might remotely match a lupine profile. This isn’t impunity round my woods’ neck. One must imagine themselves perceived innocent when in human skin to think so.

White was the word. Mighty white.

Even potential anonymity is contingent. In most of the folklore I’d read, a trope that sticks is injuries a werewolf sustains in either form carries over to the other. Lose a hand? You become a wolf sans paw. Sustain a slash across your muzzle, you wake to a gouged nose in the bathroom mirror.

No. The werewolf as beast or fictional half-person/half-beast was not free of any control I didn’t ultimately feel subject to. An alibi means nothing if no one de-escalates before firing that silver bullet.

What the werewolf has that I want is a transformed relationship between body and place, this by way of their keener senses. They would know things about themselves in their surroundings I never could.

I stand sometimes, in a still wind, sniffing, listening. I peer in the darkness trying to understand what shapes light doesn’t see.

I think, too, of werewolves’ powerful musculature, I imagine it coupled with my new senses, enhancing my proprioception—“perception or awareness of the position and movement of the body,” allowing me to take joy in motion through space, instead of fear. Is that freedom from morality? Whose? And is its fleetingness freedom at all? Contingent upon when the pale moon comes to shine its face on me?

This would be a time to know better the briar’s signal and noise. That this knowing could become part of my body’s memory, not as a dream but as a passage of conscious time, astonishes me.

Monstrous strength to fight those who harm me? Sure.

But when I dream of revenge, I’m not proud to say, I don’t care for ambiguity about my identity.

Later for a mask of fur and fangs.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Optic Subwoof by Douglas Kearney. Copyright © 2022. Available from Wave Books.

Douglas Kearney

Douglas Kearney has published seven poetry collections, including Sho (Wave 2021), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, PEN Award, and the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, and Buck Studies (Fence Books, 2016), winner of the Theodore Roethke Memorial Poetry Award, the CLMP Firecracker Award for Poetry, and the California Book Award silver medal for poetry. M. NourbeSe Philip calls Kearney’s collection of libretti, Someone Took They Tongues. (Subito, 2016), “a seismic, polyphonic mash-up.” Kearney’s Mess and Mess and (Noemi Press, 2015), was a Small Press Distribution Handpicked Selection that Publisher’s Weekly called “an extraordinary book.” He has received a Whiting Writer’s Award, a Foundation for Contemporary Arts Cy Twombly Award for Poetry, residencies/fellowships from Cave Canem, The Rauschenberg Foundation, and others. Kearney teaches Creative Writing at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities and lives in St. Paul with his family.