On the Rich and Radical History of Nightwalking

Bianca Giaever Explores Nighttime Rituals of Losing and Finding Oneself

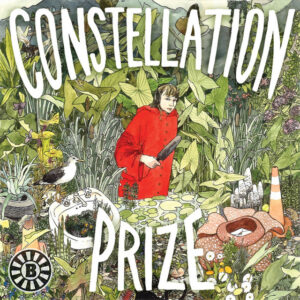

Several months into the COVID-19 pandemic, I was feeling listless, isolated and bored. Confined in a Brooklyn apartment with my roommate, I spent my time working at my computer and taking the occasional walk around our neighborhood. But one day, I received an unusual message. The environmental writer Terry Tempest Williams had heard my podcast, Constellation Prize, and she was inspired to do a project together.

Terry suggested that we go on nightwalks together from the new moon and the full moon, write each other a letter after each walk and record these letters in audio.

Terry saw nightwalking as a way to conquer fear, and a powerful metaphor for persevering through the unknown. Nighttime, to her, was a space to continually lose and then find oneself, to cast off grief, to contemplate, and to come face to face with the Divine. When you walk at night, your senses are heightened, and you have no choice but to surrender, fully, to the present.

For the next fourteen days, we went walking for an hour each night, observing as the growing moon revealed more and more of the landscape. The result was a four-part podcast series, told through these letters, and a meditation on God.

When you walk at night, your senses are heightened, and you have no choice but to surrender, fully, to the present.While working on this podcast, I spoke to two experts who research the night: Roger Ekirch, author of At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, and Matthew Beaumont, author of Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London. Throughout our conversations, I gained a greater understanding of nightwalking’s cultural significance and history.

*

Roger Ekirch got the idea to study the night from his “brilliant friend,” in a conversation about topics that would be “far more interesting and far less tedious” than their current dissertation topics. Once his dissertation was finished, Ekirch began researching the nighttime from a historical perspective, reading through hundreds of diaries, court records, and newspapers about how people in preindustrial Europe spent the nighttime hours.

Before the 19th century, many people slept in two separate cycles, going to bed right after dark and waking up again between midnight and 2 AM. This parenthetical space was a time to read, pray, and potentially have sex before returning to sleep until sunrise. “It’s a reminder that sleep is a cultural phenomenon,” said Matthew Beaumont.

The “two sleep” phenomenon was merely one aspect of what Ekrich termed early modern Europe’s “distinct nocturnal culture,” a culture marked by, “how people dressed, what they ate, the medicine they ingested, the work they did, but also in terms of attitudes toward authority in terms of church and state, and in terms of relations with their peers.”

Night represented liberation for both the wealthy aristocrats, who were free to escape strict social expectations. And it also meant freedom for lower classes and serfs, who could escape from their superiors at night.

But “going abroad,” as traveling at night was called then, came with its own set of risks. God and Satan were not theoretical—they were very real entities that night travelers needed to contend with. They would recite special night spells to keep the dark spirits away, and summon the protection of God. Additionally, there were physical risks to account for. “You might stumble into an open well,” said Ekirch. “Or a river, or fall down a hillside.” By the time they became adults, travelers had committed every stair in their house to memory, as well as every creek, hill, and shrub to avoid. “In Scandinavia, it was routine to push furniture against walls before it became dark, lest you run into a chair if you needed to get up in the middle of the night,” said Ekirch.

During the Romantic period, writers and artists praised the night, seeing darkness as an opportunity to embrace mystery and escape Enlightenment rationalism. Wordsworth, for instance, praised the moonlight in “A Night-Piece,” extolling the virtues of the night’s “peaceful calm” and “solemn scene,” while Edgar Allen Poe confronted the terrors of being up at night: “Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there, wondering, fearing, doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.”

The French concept of the “flaneur” originated in the 18th century, but the term wasn’t popularized until the 1860’s when it was adopted by writers of the Romantic period. In 1863 Baudelaire wrote of the flaneur as a “passionate spectator” who feels himself to be “at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world,” living in a state of aesthetic pleasure and contemplation. But perhaps the greatest night-flaneur of all was Charles Dickens, who Beaumont christened “the poet laureate of nightwalking.” In the 1850’s, he claimed to walk up to 25 miles on some nights, during a tumultuous period in his life after his father died and his marriage was falling apart. “Frankly, he was having an affair at the time,” said Beaumont. “So he’d walk.”

In an 1860 essay about nightwalking, Dickens described the exquisite pleasure of losing himself and his sense of reality. But these pleasant hallucinations could quickly flip—a river that was beautiful in one moment would suddenly acquire an “awful look”, the lights bouncing off its surface reminding him of “spectres of suicides.”

*

In the late 18th century, the sport of athletic walking, or pedestrianism, emerged in Britain. Its origins reflected the brutal class dynamics of the time: wealthy aristocratic class bet on their carriage footmen in walking competitions at state fairs. From there, long distance walking competitions began, covered by the press. In 1809, Captain Robert Barclay Allardice, “The Celebrated Pedestrian,” walked one mile every hour for twelve days straight.

Walking at night can be a radical act, a quiet space outside of the grind of the daytime hours.Pedestrianism caught on in the United States after the Civil War. In 1867, Edward Payson Weston was awarded a prize of $10,000 after he won a 30 day walking competition from Portland, Maine to Chicago. Pedestrian walking fever culminated in 1879, when 10,000 spectators gathered at Madison Square Gardens to watch walking athletes compete in the Great Six Days Race. Over the course of a week, the athletes walked 450 miles in laps.

*

For centuries, curfews have been used as a tool of repression and political control. In an episode of the podcast This Day in Esoteric Political History, about Nightwalking, historian Kellie Carter Jackson describes the long walks that Frederick Douglas’ mom would take at night to see him. “She would work from sun up to sun down, then walk twelve miles to where Frederick Douglas was housed on another plantation,” she said. The restraint of movement on Black Americans continued for decades. In the Jim Crow era curfews prevented Black Americans from entering certain neighborhoods at night, and in the Civil Rights era curfews were used to dispel protests.

Since then, the night has been reclaimed by activists as a space for political resistance. In 1965, civil rights advocates marched from Selma to Montgomery marches over the course of five days, holding rallies every night. In 1978, several hundred Native American activists and allies walked from San Francisco to Washington DC over the course of five months, advocating for land and water rights.

*

Sitting in 21st century Brooklyn, it often feels that humans now control the night. With the flip of a switch, we can control when and how we allow the night in. In his 1933 essay “In Praise of Shadows,” the writer Junichiro Tanazaki warned of the eternal access to light, and the very western mindset of immersing the world in light. “If light is scarce then light is scarce…But the progressive Westerner is determined always to better his lot,” he wrote. “From candle to oil lamp, oil lamp to gaslight, gaslight to electric light—his quest for a brighter light never ceases, he spares no pains to eradicate even the minutest shadow.” Tanazaki writes of his love of a glimpse of flesh through the dark folds of fabric, and of the way a gleaming piece of sushi sings out to him in a darkened room. He even writes of the joys of using the toilet in a dim, shadowy bathroom—if grime exists in the corners, he’d rather not know.

Terry taught me, through our walks, about the importance of night that is particularly applicable to artists. Walking at night can be a radical act, a quiet space outside of the grind of the daytime hours. “On one hand, you know, I’m walking with beauty,” she told me. “On the other hand, I’m walking with fear. And how do you bring these two hands together in prayer?”

__________________________________

Constellation Prize, a podcast from The Believer magazine, talks to subjects about their existential problems—how art, God, and loneliness fit in their lives. The newest episodes include Nightwalking, a four-part mini series featuring the poet Terry Tempest Williams.