On the Remarkable Legacy of Lewis Lapham

Elias Altman Remembers His Boss' Advice on Writing, Editing, and When a Deal's a Deal

You only meet a few people in your life who, like stars, exert a pull so strong that they alter its trajectory completely. I was lucky enough to enter the orbit of the legendary editor and essayist Lewis Lapham. A week ago, I attended his memorial service. He died on July 23 in Rome at the age of eighty-nine.

Lewis came into view in 2002, my junior year of high school—a chance meeting in the library. Having completed a U.S. history exam for which I’d pulled an all-nighter, I flopped out on a soft chair next to the periodical rack to doze it off. For plausible deniability, I reached for a magazine to lay across my lap.

I hadn’t read Harper’s before, but that white cover stood out. On it, a painting of three horses paired with an essay by someone who sounded like a passionate preacher from the Second Great Awakening—a term that had been on the test—John Jeremiah Sullivan. The opening piece was titled “The Road to Babylon.” It was by Lewis H. Lapham, another name you don’t forget.

I’d never read anything like it. A wry, elegant yet savage broadside against the myriad forces then conspiring to invade Iraq—from President George W. Bush and Senator Joseph R. Biden to talking heads and editorial pages. No one escaped the writer’s scorn, and he was relentlessly funny. Except when he wasn’t. Midway through the essay was a moving retelling of the tragic story found at the heart of Thucydides: the Athenians’ doomed Sicilian Expedition of 415 BC, which precipitated the destruction of the world’s first democracy.

I didn’t know it then, but we would invade Iraq the following March, destroying countless lives, to the eventual tune of $1.9 trillion (another $2.26 trillion in Afghanistan), and the disastrous War on Terror would indeed become an instrument and emblem of America’s decline. I didn’t know this then, either, but I was reading vintage Lapham—the torch-taking to self-righteous cant, the enlisting of history, the irony, the understatement. Vintage Lapham, yes, but also the pearl-like coalescing of an idea that would become the magazine Lapham’s Quarterly, where, five years after that sleep-depriving encounter in the library, I found myself interning on the inaugural issue.

I didn’t know this then, either, but I was reading vintage Lapham—the torch-taking to self-righteous cant, the enlisting of history, the irony, the understatement.

*

It’s a strange thing to have a walk-on role in the fifth act of a great man’s life. Lewis was exactly fifty years and one month older than I was. Twenty-two when I first entered the small Irving Place office—opposite The Nation—I understood that I would get to know Lewis in a specific mode, as an elder statesman of American letters. There had been Lewis the fresh-from-Oxford beat reporter at the San Francisco Examiner and the New York Herald Tribune starting in the late 1950s; Lewis the roving longform journalist for the Saturday Evening Post and LIFE throughout the ’60s and ’70s; Lewis the unlikely editor of Harper’s from 1976-1981; and of course Lewis the prolific essayist for and editor of Harper’s again from 1983-2006. There he resurrected the Notebook, which he wrote, redesigned the cover, devised the Index and Readings sections, and published the first works by, among many others, Annie Dillard, David Foster Wallace, Barry Lopez, and the aforementioned Sullivan. These Lewises were not my Lewis.

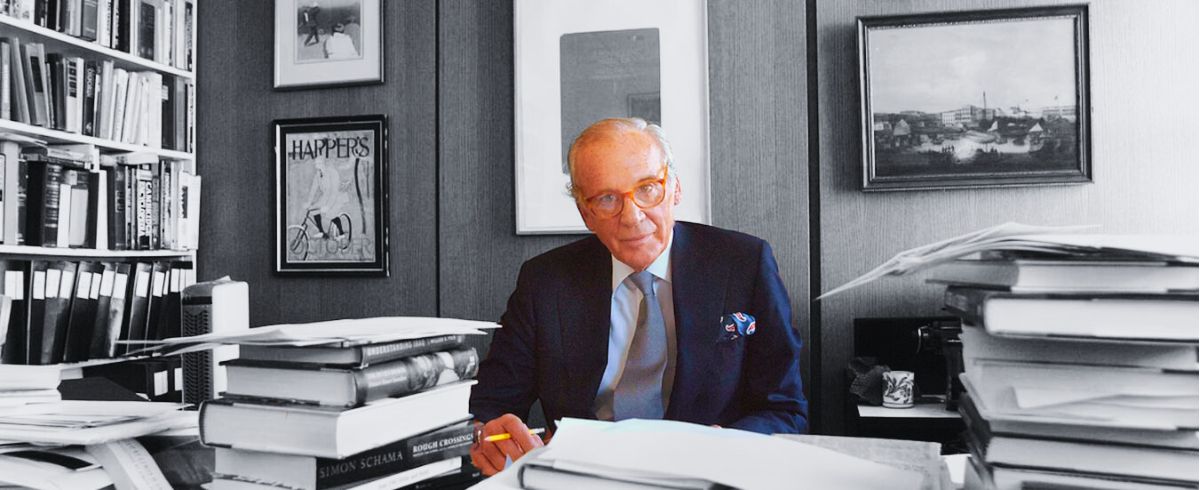

But if the Quarterly was his final act, he showed no signs of slowing down. My first time seeing him, day one of the internship, Lewis was in his glass-walled office at a massive wooden desk, cigarette smoke twisting toward the ceiling as he wrote with a black Pilot pen on a yellow legal pad and sipped from coffee in a de-lidded Greek-style paper cup from “the man in the box” (what he called street vendors). The other intern and I sat side by side, fifteen feet away. All we needed to do was glance over our shoulders to observe him through the glass, as if the worthy subject of a scientific study, scribbling with a smile or talking to himself, dressed to the nines—old tassel loafers (no socks), pinstripe suit, long tie, white dress shirt, cufflinks.

First days are slow for interns, so I mostly sat around and listened. What I heard was what I’d come to hear often. Lewis wasn’t talking to himself, he was dictating an essay (and some correspondence) into a tape recorder, which his executive assistant and first reader Ann Gollin typed up and returned to him. He proceeded to edit longhand—an occasional chuckle when he was really hitting his mark—and re-dictate. And the process started again, the essay growing each time by one, three, maybe four paragraphs, if he was lucky. “Always stop in the middle of a paragraph,” Lewis would tell me later. “That way you’ll know where to begin tomorrow morning.”

When I went home that first day at six, he was still in his chair, setting down his pen and drawing out from the pack another cigarette. For me, Lewis will always be at that desk.

At the end of my internship, Lewis called me into his office. “Elias, you know I want to hire you, don’t you?” I said I did not know—and I didn’t. “The thing is, I don’t really want to pay you.” He said he hoped that a writing gig he’d recently passed along to me would offset what he was prepared to offer. The assignment in question was one he and the late Peter Mayer, founder of Overlook Press and bold publisher of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, had cooked up over drinks. A slim satirical volume in the style of an annual report to shareholders, like ExxonMobil extolling its accomplishments and positive outlook on new reserves to be drilled for in Alaska, only this report would be issued by the Al Qaeda Group—expanding into emerging markets, forging exciting strategic alliances. (I eventually wrote 25,000 words, but it never did get published, if you can believe it.) I looked at Lewis and said, in a way I can only blame him for, as being around Lewis made you want to speak like him: “Lewis, I don’t have a silver spoon, so I’ll need to eat like everyone else.” He smiled, then grumbled. The Quarterly was run by a nonprofit and, he intimated, he’d barely been able to get the thing off the ground. I was done for, I thought, leaving his office.

A week later, I was on staff. I stayed for seven years.

*

Lewis was generous. He bought cartons of Parliament Lights and smoked them in the office and let us smoke them with him and, if we asked, said, “Of course, have a pack.” Usually one night a week, maybe two—three if the essay was going well—he would invite anyone working past six-thirty to join him at Paul & Jimmy’s, an unfussy Italian restaurant around the corner.

“Maestro!” Lewis said to the waiter. “I’ll have vodka”—holding up his thumb and pointer finger as measurement—“in a wine glass”—his flat hand slicing the air—“very cold. Kiddo?” Once we had our drinks, we talked—about the current issue, his essay, the latest political scandal; the times he played piano for Thelonius Monk, dove for sunken treasure, or met the Maharishi; why he loved Patrick O’Brian and John le Carré, Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce. Amid tall tales and bon mots—he loved if you could quote things—Lewis sometimes said, “Kiddo, shall we order some appetizers?” Around my first or second year at the Quarterly, I became the Appetizer Czar, an appointment that, since I was the youngest person on staff (and the youngest child in my family), I relished, performing as diligently as I would any task in the office.

The recessed filters, Campari sodas, croquettes and caprese—these were the tangible gifts that felt so special to accept from him, but the real heart of his generosity was the trick he pulled with time. He gave it away freely, as if he were Prince Gautama and it a worldly possession in need of renunciation. He seemed always to have the time to teach you—although he’d bristle at being the subject of that verb—and to listen, which was more impressive. Lewis was a man of strong opinions and his name was on the door, but it didn’t matter if you were an executive editor or an intern or “the man in the box”: if you said something smart, even just surprising, he took it as seriously as if it were printed on A1 of the New York Times. (Probably more seriously, given their history of manufacturing consent.)

Lewis inspired among people who worked under him a remarkable degree of allegiance. He possessed the politician’s or cult leader’s knack for making you feel it’s-just-you-and-me during a conversation—his trained eyes, that smile, the laugh. But it wasn’t a put-on or a ploy, it was a principle, and his pleasure. You never got the sense that, down the road, he might suggest it was time to throw back a cup of Flavor Aid and meet your maker, or press you into invading a country under false pretenses. You didn’t strive to please Lewis so much as to delight him. He wasn’t interested in followers, clones, or acolytes (although we existed). What he was looking for were playmates.

For all his erudition and elegance, Lewis was a child. And I mean that in the way only a new father can, seeing how by comparison the rest of us—forced to become “sivilized” as Mark Twain said, puffed into “phonies” as J.D. Salinger had it—slowly and steadily become deracinated from our playful terroir. For Lewis, the greatest game was running a magazine. He played with words and ideas like a beautiful set of hand-hewn stone blocks. He loved the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga’s book Homo Ludens, about the formative role of play in human culture, its five defining characteristics: “1. Play is free, is in fact freedom. 2. Play is not ‘ordinary’ or ‘real’ life. 3. Play is distinct from ‘ordinary’ life both as to locality and duration. 4. Play creates order, is order. Play demands order absolute and supreme. 5. Play is connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained from it.” Lewis discovered and disseminated a way of life and work that was essentially play. So I guess, in the end, he tossed rules 2 and 3 into the trash.

*

Here are some things Lewis Lapham taught me. If you’re going to reject a writer’s manuscript, do so quickly and honestly—don’t make them wait for weeks and then fall back on the old: “I loved this, but my boneheaded colleagues…” The writer of a piece has to be curious, and their curiosity has to make you curious, too. Find the best writers and ask them about what interests them (which is how I got to edit Anne Fadiman, Pico Iyer, and Daniel Mason). Edit with a pen, as if you were conducting a symphony. Writers have been told their entire lives they shouldn’t do this or that, and certainly not for a living, so arm them lavishly with confidence (but do not overpay them). When assigning, your existential role is to give writers permission, or even, on occasion, make them aware of their responsibility. Take Barbara Ehrenreich. Over a fancy lunch with Lewis one day in the 1990s, Ehrenreich wondered aloud how women screwed over by welfare reform would manage to make do on $6 or $7 an hour and said that some journalist should go out and see what it was like, old school. “I meant someone much younger than myself,” Ehrenreich later recalled, “some hungry neophyte journalist with time on her hands. But Lapham got this crazy-looking half smile on his face and ended life as I knew it, for long stretches at least, with the single word ‘You.’” Ehrenreich went on to write Nickel and Dimed.

The best writers love being edited; it’s the bad ones who resist. Writers don’t always know what’s best about what they write, and usually things only start to get really interesting on the final page of the first draft. The set-up of an essay is everything—a great title is imperative, too—so nail the “nut graf,” establishing the goddamn stakes of the thing early on and clearly. Editing is often compared to surgery in the form of incisions and extractions—the scalpel—but what struck me most about Lewis’s handiwork was how he sutured, stitching sentences together as he read, ever-tightening. (I still have a copy of a manuscript he edited, in front of me, in fifteen minutes.) Most writing has the charm and originality of a prefabricated henhouse, so don’t be a party to it. Substance is a must, but if the prose doesn’t sing, where’s the pleasure in reading it? Syntax is meaning. Still, don’t be afraid to sprinkle a bunch of “TK facts” throughout a writer’s manuscript to keep them honest.

I once showed Lewis a document written by longtime copyeditor and drama critic Wolcott Gibbs entitled “Theory and Practice of Editing New Yorker Articles,” which he’d prepared for Harold Ross in the 1930s. While Lewis would never have done anything so gauche as write out thirty-one rules for editing, his favorites were: “1. Writers always use too damn many adverbs… 20. The more ‘as a matter of facts,’ ‘howevers,’ ‘for instances,’ etc., etc., you can cut out, the nearer you are to the Kingdom of Heaven… 31. Try to preserve an author’s style if he is an author and has a style.” But Lewis’s most bankable advice wasn’t about editing at all. As a literary agent working in what are not widely seen to be the halcyon days of publishing, Lewis’s statement about managing expectations always serves me well: “A deal’s not a deal until you’re counting the cash in the mensroom.”

After seven years of working at the Quarterly, having put thirty 224-page issues to bed and earned enough of Lewis’s respect to get to edit him (lightly), I walked into his office. Smoke swirled above a cigarette on his crystal ashtray; he looked up from his legal pad, put down his pen. I told him I was leaving to become a literary agent. I’ll never forget it. He laughed—that rich baritone I loved. “Wait…are you serious?” He thought I’d leave like so many others before to join the mastheads of magazines with bigger payrolls, or to light out for the territories, chase stories as a writer—but agenting, I mean? I was ashamed that I couldn’t mount a solid defense. I had little sense of what I was jumping into, only that I needed to jump. We went out for a drink at Paul & Jimmy’s. We got drunk.

I didn’t know it then, of course, but my conception of being an agent is Laphamesque from stern to bow. Find writers you want to learn from. Give them permission. Work hard. I wanted freedom, I wanted to play, I wanted to make my own little magazine of books that, if all goes well, have a nice long shelf life. And I’ll take 15% of the advance—and of the royalties, but I was taught to be a realist, so I’m not counting on that.

*

I’ll miss Lewis and a hundred small things about him. The way he fixed his glasses after they slid down his nose, with the pointer and middle fingers of his right hand, with all the soft grace of a white-gloved butler. The way he said “Fan-TAS-tic” and grinned about something that really lit him up. How he got so outraged by the New York Times editorial page—and read it every day. And, although I’m not sure why, the way he practically sneezed his go-to word when he was annoyed or frustrated, “GOD-dammit”—the first syllable like a pitcher’s wrist floating back for a split-second before it snaps forward to hurl a 103-mph fastball.

I used to try to analyze Lewis’s psychology—what sorts of things had made him who he was, what determined his singular temperament—but it was like craning my neck in hopes of catching a glimpse of the dark side of the moon. In an issue of the Quarterly, he once elected to use a pull-quote from Andy Warhol—someone in all ways opposite to Lewis, and whom he loathed—and it struck me for its resonance: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings, and films, and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” Lewis was right there; that’s who he was, in person and on the page. With a writer whose default mode was ridicule—it doesn’t get much better, briefer, or more brutal than his elegy for Tim Russert—and whose cast of mind was firmly ironic, you might miss his other side. You only need to look from a slightly different angle—as with Hans Holbein the Younger’s trompe l’oeil The Ambassadors, which Lewis loved—to see how much he cared, how he loved to laugh, what fun he was. While putting together the Quarterly’s Comedy issue, the quotation he selected for the first page was from W. H. Auden: “Among those whom I like or admire, I can find no common denominator, but among those whom I love, I can; all of them make me laugh.” I’m sad I’ll never laugh with Lewis again.

I used to try to analyze Lewis’s psychology—what sorts of things had made him who he was, what determined his singular temperament—but it was like craning my neck in hopes of catching a glimpse of the dark side of the moon.

“The best thing for being sad,” the magician Merlin says to the once and future king in T.H. White’s novel, “is to learn something.” This was a favorite passage of Lewis’s, lovingly read at his memorial by one of his grandchildren, and a life-philosophy he said writer-adventurer Peter Matthiessen embodied when eulogizing him in Hotchkiss Magazine. I suppose it’s unavoidable that when writing about other people we say just as much about ourselves: this is Lewis—and it’s how he lived so long (despite all those Parliament Lights) and so happily (despite the essay-writing doldrums). He lived long and well because, like what Hokusai said about being seventy-three and why Pablo Casals still practiced at ninety (“Because I think I’m making progress!”), Lewis never stopped trying or learning. He read, listened, and surrounded himself with young people.

The last time I saw him, Lewis was surrounded by young people. It was on the evening of December 18, 2023. As the mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day, I walked out of the rain and into Paul & Jimmy’s. The occasion wasn’t a cause for celebration. The Quarterly was going on hiatus, and Lewis was decamping to West Palm Beach. We were seeing him off.

I stood there, seeing him among his staff, and was momentarily sad, then glad, for how the show goes on without you, how he must’ve called most people “Kiddo,” how he always gave everyone his time. That was the refrain of his memorial service. While there may be only a handful of people who reroute someone’s life, Lewis exerted this gravitational pull on hundreds and hundreds of us, playing the same role every time. That is integrity.

For some reason, as I approached the six tables pushed together, the only seat still available was to Lewis’s immediate right. I sat, introduced myself to the staff, said hello to Chris Carroll, former Quarterly intern and current editor of Harper’s, and tried to listen in on Lewis’s conversation. When he sensed a presence, Lewis turned and saw me, “Oh my god. Elias, how the hell are you?” Before I had a chance to reply, the waiter came up and interrupted us. “Would you like to order any food, Mr. Lewis?” Without missing a beat, Lewis tilted his head at me, smiled his half-smile, and said, “Elias will take care of that. He was always good with the appetizers.” I took a quick headcount, and got to work.

Elias Altman

Elias Altman is an agent at Massie & McQuilkin. Books he represents have received or been named finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Critics Circle Award, National Book Award, Dayton Literary Peace Prize, Plutarch Prize, New York City Book Award, and the MAAH Stone Book Award. His writing has appeared in Vogue, The Nation, The Columbia Journalism Review, The Georgia Review, Lapham’s Quarterly, and is forthcoming in n+1.