On the Playwright Sarah Kane and Radical Ekphrasis in Contemporary Poetics

Andrea Abi-Karam on Writing To The Dead

Ekphrasis is a way to talk to the dead.

Traditionally, ekphrasis is a descriptive transference of an artwork from one medium to another. Radical ekphrasis is also a vehement re-remembering of those who have been systematically erased. My work, including in this area, suggests that people can and should weaponize language as a tool of empowerment. It holds that poetry, as a shareable tactic, makes public the cost of colonial violence to achieve what headlines, data, and source texts cannot.

I cut my teeth as a writer in the razed hall of postmodern feminist playwrights of the 1990s. I’m thinking specifically of Sarah Kane and Caryl Churchill, whose plays actively disintegrate the fourth wall, breaking down any perceived separation between reality and art. Their work refuses the notion of a clean compartmentalization of violent experiences and asserts that violence is systemic, interrelated and relentless. These playwrights crafted works that the audience members carry with them even after they exit the theatre. Spatially, the audience takes the play with them, undermining structures of separation and compartmentalization and thus dissolving the borders between art and reality, actor and audience, theatre and street, participant and witness. The work’s expansiveness beyond the theatre implicates the audience’s complacency and urges them to act.

Sarah Kane’s plays re-inscribe the utter magnitude of violence directly, intimately, and brutally, such that the audience may need to look away, but they will never forget. In Blasted, Kane draws attention to the Bosnian War by zooming in on a hotel room scene of domestic violence that degrades rapidly as the war spills into the room, crumbling the walls between outside and inside along with any sense of safety. Kane draws a powerful line from the gendered violence taking place in the hotel room to the systematic mass rape by military forces that was a signature of the Bosnian War.

I think about this slippage between micro and macro all the time. When a mass devastation occurs, how is it being registered? What are our responsibilities as poets to attend to it? How can poetry make public that which has been systematically redacted in order to uphold the nation? How can poetry disarm the surveillance state and return public space to those our governments have sought to expel?

Blasted is incredibly violent. The given stage directions are unimaginable. It both forced me to become educated about the Bosnian War and gave me permission to unravel preconceived constraints of genre. In 4.48 Psychosis, Kane’s final play before her death by suicide in 1999, she unravels the construct of a play as having discrete characters, stage directions, dialogue, and set, and instead offers what I interpreted as a poem with an ambiguous number of speakers who grapples with mental health, insomnia, and depression.

Kane, who died at 28, left us with only a single volume of plays: Sarah Kane: Complete Plays: Blasted; Phaedra’s Love; Cleansed; Crave; 4.48 Psychosis; Skin. As a young and frequently devastated by literature undergrad, I was wrecked by these facts. I selfishly wanted more. I overidentified with her struggles with insomnia, frequently running on four hours or less sleep myself; I would rewrite lines from 4.48 Psychosis in various class notebooks and write new poems in her style. I felt that the conversation had been cut short and wanted to bring her back. I wanted more of her work, more of her.

I wanted to continue the conversations that her work began. Ekphrasis is a way to talk to the dead.

My obsession with Sarah Kane—and my need to continue the conversations that her work began—became the root of my practice of radical ekphrasis. I wanted to continue the conversations that her work began and draw attention to her short but impactful complete works. Ekphrasis is a way to talk to the dead.

*

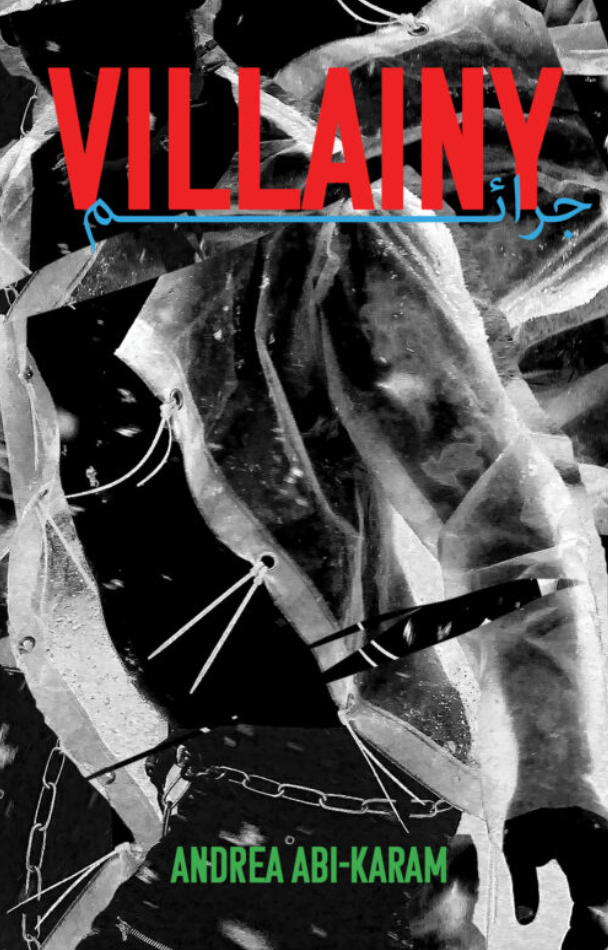

In December of 2016, the Ghostship Fire in Oakland, California, where I lived for six years, claimed the lives of 36 friends and community members. This sudden personal and collective loss shocked me, and so many others, into a durational period of grief unlike any that I had ever faced. I wrote Villainy in the wake of the fire, the 2017 Muslim Ban, and the rising veil of new fascism in the US. In the early months of this debilitating grief, my friend took me to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) to see Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta on a grey afternoon in January 2017. In a darkened, cavernous room of BAMPFA, 21 of Ana Mendieta’s Super 8 films were projected on the walls, continuously looped. The room was empty save for one or two other viewers—it almost felt like a private viewing, an utterly intimate filmic window into Ana Mendieta’s life and work.

I was instantly transfixed. Rather than browsing and getting a sense of the whole show, I sat in front of Projector 6 and began to write. I moved about the room in this fashion, sitting on the floor in front of each film and writing pages and pages. I had been previously familiar with her earthworks but this was the first time I experienced her films. I knew that her life had been cut short by her husband, Carl Andre, who pushed her out of their 34th floor apartment window to her death. Whose art and narrative as a woman of color had been erased. I knew that she had so much more to create than what gendered violence had afforded her.

Sitting on the floor of the gallery, haunted by the force of her films, hardly able to see the pages in front of me, I wrote an early version of what became the I GOT LOST / I GOT DELETED section of Villainy. Deep in the shadows of my own grief for the friends I’d just lost to the Ghostship Fire, I was struck by the weight of her body on the screen, the strength of her breathing buried beneath rocks or face down in a river, the messages she inscribed on the wall and on her skin, the contortions of her body and earth, the immensity of the void she left behind.

I was drawn to Ana Mendieta’s durational and physical commitment to words and her own body as weapons of resistance against erasure. I was floored by the repeated earthworks in Volcán, where Mendieta carved her outline in the earth using the explosions of gunpowder, insisting on inscribing and connecting the outline of her body to the earth. I could barely look upon Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (Firework Piece), and Untitled: Silueta Series (Old Man’s Creek), which contained fireworks and flames contrasted against the night. I loved the idea of Mendieta’s outlines being burned onto reel after reel of giant Super 8 film, refusing to be folded up into something small to be hid away and forgotten.

I didn’t enter the gallery with the intention of placing my own gaze and ongoing experience of loss in conversation with the collage of Mendieta’s films. Mendieta haunted me. Mendieta channeled me. In spite of her ecofeminist foundations and legacy, art institutions such as the SFMOMA continue to sideline her and show her husband Carl Andre.

*

In the fall of 2018, I went to see the David Wojnarowicz retrospective for the second time at the Whitney. I had first attended in August on a first date with someone. My second visit was with two friends, one of whom quickly became my new lover. On both visits, I experienced the work on the premise of desire. The show had many rooms filled with paintings, sculptures, films, audio recordings, journal entries, and photographs. Meandering through Wojnarowicz’s abundant mausoleum of work, it was difficult to properly attend to everything. There was so much work created before and during the AIDS crisis—which of course at the time was denied, ignored, and queers were relegated to death by state abandonment.

The show, especially Wojnarowicz’s film works, utterly turned me on. In reading the museum copy for the artworks, my desire was quickly met with rage. The Whitney, whose Vice Chairman owns Safariland Group, a company that produces projectiles and tear gas used by the Israeli military against Palestinians, valorized Wojnarowicz as a “singular” artist, lifting him out of his context of queer community within the AIDS crisis.

I was frustrated and enraged with the narrative the Whitney sold, which is clearly dispelled in Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz by Cynthia Carr with the countless queer friendships, collaborators, lovers, and community in which Wojnarowicz created. Like the grief I felt experiencing Mendieta’s films, I mourned the void of queer mentors my generation has as so many would-be mentors were lost to mismanagement of the AIDS crisis and the state’s dismissal of queer existence.

With this desire and rage I wrote the first draft of HOLD MY HAND, which appears in the final section of Villainy. Radical ekphrasis is a way to talk to the dead.

I don’t want an archive of queer cruising that you have to pay a $20 cover to see. I want actual queer cruising: public space that’s no longer mutilated by gentrification, policing, heteronormative ideas of what’s admissible in public, ugly condos, and museums whose board members profit from ethnic cleansing. Decolonial poet Aimé Césaire offers these criticisms regarding the museum as an inherently colonial project: “And the museums . . . all things considered, it would have been better not to have needed them; Europe would have done better to tolerate the non-European civilizations at its side, leaving them alive, dynamic and prosperous, whole and not mutilated; that it would have been better to let them develop and fulfill themselves than to present for our admiration, duly labeled, their dead and scattered parts; that anyway, the museum by itself is nothing; that it means nothing, that it can say nothing, when smug self-satisfaction rots the eyes, when a secret contempt for others withers the heart, when racism, admitted or not, dries up sympathy.” With a fiercely anti-singular and polyvocal construction, Villainy imagines a militant collectivity in public space—beyond and while breaking institutional walls of museum, prison, and border.

Through attending to the works created by Ana Mendieta and David Wojnarowicz and responding to them in language, I developed my practice of radical ekphrasis, a strategy refusing the erasure and deletion of the targeted other by creating space for their life and work to be in conversation with the contemporary moment. Radical ekphrasis creates space for conversation that wouldn’t otherwise be possible due to death—all too often, premature death. Radical ekphrasis creates spaces for counter-institutional narratives to flourish. In encountering and responding to these works, falling in love with and then losing, I trace my own lineage of resistance, resilience, and loss.

____________________________

Villainy, by Andrea Abi-Karam, is available now from Nightboat Books.

Andrea Abi-Karam

Andrea Abi-Karam is a trans, arab-american punk poet-performer cyborg. They are the author of EXTRATRANSMISSION (Kelsey Street Press, 2019) and with Kay Gabriel, they co-edited We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics (Nightboat Books, 2020). Their second book, Villainy (Nightboat Books, Sept 2021) reimagines militant collectivity in the wake of the Ghost Ship Fire and the Muslim Ban. They are currently working on a poet's novel.