On the Places and Poetic Forms of the Black Southern Poet

Khalisa Rae Considers What It Means to Write in the “Southern Tradition”

The Southern writing tradition has always been the fertile ground for fire. Dry weeds exist, yet the soil is rich. For me, the South is a living, breathing thing: a ghost, a bay window, a river’s edge, a magnolia tree, a stained-glass hymn.

Like many great poets that came before me, I am not a native of the South. I migrated to the Southern states to feel connected to my ancestors and find language and culture; to be more attuned with Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison, Nikkey Finney, Maya Angelou, and more. What links these great Southern Black poets is their ability to capture the light and the darkness of the South. Each rendered the region as a dichotomy of beauty and pain: music in melancholia, the trauma and tumbling hills. All exist here, and this juxtaposition always defined the execution of their work.

Famous for “Weary Blues” and “Harlem,” one poet who sang through the pain and preserved Southern Black writing tradition was Langston Hughes. Hughes was born in Missouri and influenced by the vibrant blues coming from nearby Kansas City concert halls. Traditionally the blues stanza contains three lines—the second line repeats the first, and the third line carries out the rhyme and is usually set to twelve bars of music. The blues song structure derived from African American field workers surviving inhumane treatment. Those work songs sent coded messages to the other slaves, conveying feelings of discontentment and sorrow through repetition and metered verse stanzas.

Langston later left Missouri for Harlem but carried that southern blues with him. From his rhyming couplets to the usage of off-kilter meter and the ballad, Langston held tight to the sounds of the South. “I tried to write poems like the songs they sang on 7th Street,” he remembered in his autobiography The Big Sea. Those songs “had the pulse beat of the people who keep on going.”

For me, the South is a living, breathing thing: a ghost, a bay window, a river’s edge, a magnolia tree, a stained-glass hymn.

Poets of the Jim Crow era, especially those in the Southern Delta of Mississippi and Alabama, used the repetitive line to mimic the Southern preacher who told the story of troublesome days, with the moaning tone and mood of melancholia. One example comes in Hughes’ poem, “Morning After”:

I said, Baby! Baby!

Please don’t snore so loud.

Baby! Please!

Please don’t snore so loud.

You jest a little bit o’ woman, but you

Sound like a great big crowd.

Hughes broke the three lines of each blues stanza into six lines, as demonstrated in his poem “Homesick Blues”:

My heart was in ma mouth.

Went down to the station.

Heart was in ma mouth.

Lookin’for a box car

To roll me to de South.

The blues form gave Hughes and many others the freedom to convey the African American experience with authentic dialect and vernacular. Southern poets and writers like Paul Lawrence Dunbar, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and more used Black dialect as a vehicle to speak directly to their Black audience and preserve a language that was considered, by much of white society, to be “uneducated” and outside the canon. These writers used dialect and jargon to start a discourse around the oppressive systems that govern language.

Southern dreaming is also breeding ground for Black poets to imagine new forms and execution. Nikki Giovanni, born in Knoxville, TN, slips in and out of the natural world and laments about wanting to be a famous singer in “Dreams.” Her poetry often uses slang, lowercase letters, and hyperbole to depict Black Southern speech. In “Dreams,” the Black woman in America is told to create more realistic dreams, an idea against which Giovanni pushes with humor and free verse:

before i learned

black people aren’t

suppose to dream

i wanted to be

a raelet

and say “dr o wn d in my youn tears”

or “tal kin bout tal kin bout”

Maya Angelou and Nikki Giovanni’s writing incorporated the dialect and poetic form of Black Secular, using everyday African American speech, jargon, and metaphors as a callback to slavery. This interactive call-and-response format, often used by Black preachers and musicians throughout history, creates a conversation and community with the listener. As seen in “Still I Rise”:

“Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.”

The gritty and “undignified” language was a form of reclamation and protest to the education sector that had banned the teaching of Black Secular speech in schools.

“You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.”

What links these great Southern Black poets is their ability to capture the light and the darkness of the South.

Angelou meshes the traditional blues technique with the call and response technique while providing commentary on the erasure of Black women’s sexuality and overall prowess. Here, we have rhyming couplet verses with a repeated “chorus,” like that of a song. Poems like, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” and “Phenomenal Women” further exemplify this form:

“It’s in the reach of my arms,

The span of my hips,

The stride of my step,

The curl of my lips.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.”

Angelou’s usage of Black Secular returns to the Southern dialect, breaking the confines of so-called standard English by leaving off the end of the present participle:

“Puttin’ down that do-rag

Tightenin’ up my ‘fro

Wrappin’ up in Blackness

Don’t I shine and glow?”

Here, Angelou uses omission as a poetic tool. Her employment of the Black Secular was a celebration of Black language and our cultivation of a new communication style to respond to silencing, erasure, and othering. In other words, the Black Secular honors resiliency.

Like popular 1970s songs, Angelou’s work also used conversational lyrics and meter that slipped in and out of slang with ease to show verbal dexterity and shed light on code-switching. Her pieces often call attention to the oppressive Southern beauty standards and fetishizing Black women’s bodies. In “Just Give a Cool Drink of Water ‘Fore I Diiie,” Angelou highlights the plight of pursuing interracial relationships in a climate of racial tension:

“Never once in all their lives,

had they known a girl like me,

But…they went home.

I had an air of mystery,”

*

And yet time has not silenced the off-key dahlia song of racism, bigotry, and othering in the South that continues to be a running theme in the work of profound contemporary poets like Jericho Brown. In his debut work, Please, Jericho lays praise to his favorite soul music through testimonies of the Black queerness in the South and the music that aching tune makes. He says,

“I get high and say one thing so many times

Like Willie Baker who worked across the street—

I saw some kids whip him with a belt while he

Repeated, Please. …

God must love Willie Baker—all that leather and still

A please that sounds like music.”

Sting of violence and the refrain of please, provide the backdrop of both pleasure and pain endured by the Black body. Brown’s musical poetry once again points us to the dichotomy of the melody and menace of race, abuse,and identity. His work weaves together a harmony of multiple identities, and each poetic form is a string he strums to share a different emotion. From his reference to sex, religion, family, and field, all imagines portrayed in an interwoven sonnet.

“The woman with the microphone sings to hurt you,

To see you shake your head. The mic may as well

Be a leather belt”

That music remains in Jericho Brown’s Duplex form, which he began to develop in 2007 and used three times in his Pulitzer Prize-winning collection, The Tradition. The form owes its name to its line repetitions, which, Brown has said, remind him of a duplex-style home. Brown’s goal, with this form, was to highlight his identities— Black, queer, and from the American South—in a way that brought about a single structure. These identities would be forced together, similarly to the way in which people living in a duplex live, harmoniously or not.

Southern dreaming is also breeding ground for Black poets to imagine new forms and execution.

By letting the structure ultimately fall apart, Brown creates a new, calm chaos—he starts with couplets and adds repetitive lines that make the Duplex. This alluring disorder gives the reader lines like:

“Men roam that myth. In truth, one hurt me.

I want to obliterate the flowered field,

To obliterate my need for the field

And raise a building above the grasses.”

(“Duplex,” The Tradition)

Brown’s work is confessional, drawn from his frustration with himself. His use of repetition creates the friction of reflection while following the rhythm of struggle that characterizes southern-ness, Blackness, and queer identity.

Each Southern Black poet throughout history has found ways to fill in the space of loss by inventing forms, reclaiming old traditions, and remixing a canon that was never intended for their voices. So much has been stripped from the Black Southern poet’s lived experience, and yet out of that came a new acrostic—“Golden Shovel” form by Terrance Hayes, a Duplex, the Black Secular, blues form, and much more, proving resilience and staying power. These are our people’s sounds/determined to make their vibrations last/determined to hear their echoes repeat.

__________________________________

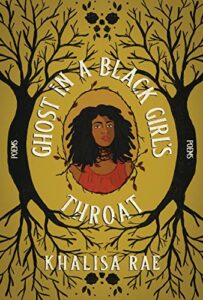

Ghost in a Black Girl’s Throat by Khalisa Rae is available now via Red Hen Press.

Khalisa Rae

Khalisa Rae is a poet and journalist in Durham, NC that speaks with furious rebellion. Her essays are featured in Autostraddle, Catapult, LitHub, as well as articles in B*tch Media, NBC-BLK, and others. Her poetry appears in Frontier Poetry, Florida Review, Rust & Moth, PANK, Hellebore, Sundog Lit, HOBART, among countless others. She is the winner of the Bright Wings Poetry contest, the Furious Flower Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize, and the White Stag Publishing Contest, among other honors. Currently, she serves as Assistant Editor for Glass Poetry and is founder of Think in Ink and Women Speak. Her debut collection Ghost in a Black Girls Throat will be released on April 13, 2021 from Red Hen Press, and Unlearning Eden in Jan 2022 from White Stag Publishing. Follow here at @k_lisarae on Twitter. Find more information at khalisarae.com.