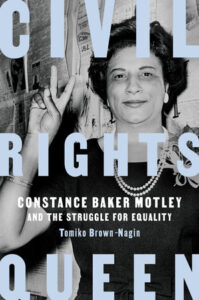

On the Pioneering Black Female Lawyer Who Took Racism to Court

Tomiko Brown-Nagin Looks at Constance Baker Motley’s Remarkable Early Career

Constance Baker Motley lacked a fancy office and an impressive title in her first job at the Inc. Fund. Office space was tight at the organization’s offices at 20 West 40th Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. The staff worked in close quarters. Until the late 1940s, not even Thurgood Marshall had a private office in the seven-story redbrick building overlooking Bryant Park. Like everyone else, Marshall worked in a tiny space with a succession of colleagues, including, at one time, Motley. During Motley’s initial years at LDF, six lawyers shared one large, high-ceilinged room. In addition to Marshall and Motley, the staff included lawyers Robert L. Carter, Franklin H. Williams, Jack Greenberg, and Marian Wynn Perry, as well as several secretaries.

As in any organization, rivalries sometimes divided the attorneys. Carter, second in command in the office, won universal praise for his brilliant legal mind and skilled courtroom advocacy. But his personality sometimes clashed with his boss’s; whereas Marshall was carefree and ebullient, Carter was bookish and intolerant of foolishness. Tall, handsome, “silver-tongued,” and an outstanding lawyer, Williams matched his talent with an immense ambition. He argued with Marshall over the latter’s “conservative” choices about which cases to take on; one blowup resulted in a shouting match that could be heard all over the office.

Perry, a white woman lawyer with deep experience in labor and employment law and dedicated to the cause of racial justice, rounded out the small staff. Tensions over case assignments arose between Perry and Williams, as well as between Perry and Motley. Racial politics shaped these dynamics. Perry and the other white women in the office were “walking on eggs,” she once remarked.

The lawyers did not always get along personally, but an unbreakable dedication to fighting discrimination united the group. The “boundaries” between “work and relationships” were “not very firm,” recalled one Inc. Fund lawyer: they were “a team dealing with hostile forces.” “We were like a family,” Motley once observed. The us-versus-them mentality encouraged a close-knit, mission-driven community.

An unbreakable dedication to fighting discrimination united the group.

Marshall’s imposing presence and gregarious personality shaped the culture of the LDF. Informality reigned during and after hours. Even as he supervised the staff, raised funds to support the organization’s endeavors, managed the increasingly long docket of cases, and argued cases in trial and appellate courts, Marshall exuded warmth and encouraged collegiality. He expected his staff to work on complicated legal tasks for long hours; each of them, secretaries included, complied. All the while, Marshall, in his playful manner, engaged his colleagues in lighthearted banter and regaled them with long stories.

For some staff this casual, fun-loving atmosphere continued after work. A devotee of long dinners and alcohol, of card playing and partying, Marshall invited close colleagues to join him in these endeavors after the workday ended. The gatherings showcased Marshall’s desire to “wear life like a very loose-fitting garment” and “worry about nothing.” The lawyers sometimes talked legal strategy during these late-night sessions; on other occasions, officemates just played cards and drank. The men in the office frequently accepted the boss’s after-hours invitations; sometimes their wives came along.

Then, on Fridays, an end-of-the-workweek ritual occurred. “Every Friday afternoon someone got a bottle of Bourbon or Scotch and a poker game ensued,” recalled Jack Greenberg. No women participated in the weekly poker games, where the men engaged in a lot of “locker room bragging” and race-inflected humor. Motley did not often take part in these social get-togethers, whether they took place during the workweek or on Fridays; most nights, she went home to Joel.

Deeply committed to LDF’s antidiscrimination mission, Motley mostly kept her own counsel. She concentrated on proving herself.

There was quite a lot for the young law clerk to do. In her earliest assignments, Motley battled discrimination against Black veterans. Requests for help poured into the Inc. Fund from servicemen who had experienced mistreatment on tours of duty and returned stateside motivated to challenge the unequal treatment. “Black servicemen,” Motley recalled, “had been court-martialed for this, that and the other” and hit with “severe penalties.” The alleged wrongdoing frequently involved sexual liaisons with white German women later labeled as “rape.” The court-martial cases required Motley to plow through “stacks of service records” so voluminous that they “reached the ceiling almost.” She also fought racially restrictive covenants; by banning the sale of property to Blacks (and Jews), these covenants perpetuated residential segregation. All of this work was tremendously satisfying to Motley, who joined her colleagues in helping to establish the burgeoning field of civil rights law.

The field developed in fits and starts as the U.S. Supreme Court became receptive to cases demanding equal enforcement of the law. Motley learned the art of litigation by observing Charles Hamilton Houston, the NAACP special counsel and pioneer in the nascent field, in strategy sessions and in court. In 1948 Motley traveled with colleagues to Washington, D.C.; she entered the majestic U.S. Supreme Court for the very first time to watch Houston challenge state and federal enforcement of restrictive covenants. The lawyer stayed in a segregated rooming house, ate in segregated facilities, and rode in segregated cabs to see Houston attack the underpinnings of an insidious form of Jim Crow—residential segregation that confined Black Americans nationwide to crowded, substandard, ghettoized housing.

Houston had prepared meticulously for the big moment, as Motley knew firsthand. In the run-up to his oral argument, she was thrilled to participate in a series of weekend strategy sessions and conference calls of “all the lawyers” across the country who were helping Houston and Marshall figure out how to argue their position. Houston prevailed, and in a series of cases that he and Marshall litigated, the lawyers established precedents that chipped away at residential segregation. Lorraine Hansberry would famously depict a Black family’s difficult move from the inner city to a white neighborhood in her acclaimed play A Raisin in the Sun. These cases made such moves possible. The experience of listening to Houston, Marshall, Robert Carter, and others prepare and argue these important cases provided Motley “an amazing legal education.”

Before long Marshall decided that Motley was ready to try cases, and she transitioned from observer to participant in court hearings. In 1949 Marshall sent her to Baltimore to share the counsel table with Houston and assist him in a case that challenged inequality in education. This case, one in a series attacking discrimination by institutions of higher education, contested a Black student’s exclusion from the School of Nursing at the University of Maryland. As Motley looked on, Houston peppered witnesses with well-phrased questions that unfolded in a sequence carefully chosen to push forward his legal strategy. Although he did not win at trial, Houston prevailed on appeal.

In addition to observing experienced lawyers, Motley wrote pleadings and briefs in a variety of important cases, taking on assignments as needed. In one of her early efforts, she aided the Inc. Fund’s successful challenge of restrictions on voting in the South Carolina Democratic Party primary (the so-called white primary). And in her first solo argument—made before the New York commissioner of education in 1949—she prevailed in an action that challenged racial gerrymandering of school district lines. Thurgood Marshall, pleased to see his protégée take this big step, accompanied her to Albany for the argument. Motley earned Marshall’s confidence in this case and in other early endeavors. She was ready for greater challenges. Next, she faced her hardest test yet: her first trial.

*

Motley’s initial experience as a courtroom lawyer took place in Mississippi, the South’s most racially repressive state and the scene of fierce and bloody resistance to the emerging struggle to overturn Jim Crow. In 1949, she journeyed to Jackson, the capital city, to prosecute a lawsuit on behalf of Black schoolteachers. The case constituted an opening salvo in a long-running battle against the racist state. In the lawsuit, Motley took her first turn as a field general in a two-decades-long war against white supremacy in Mississippi.

The senator encouraged violent repression of Black voters by “red-blooded men” who could “keep the nigger from voting” by paying them visits the night before the election.

She came on the scene in Jackson at an especially fitting time. Black veterans returning from World War II risked their lives and livelihoods by attempting to register to vote in the July 1946 Democratic Party primary. Mississippi U.S. Senator Theodore Bilbo, an ardent white supremacist, advocated Black voter suppression through all available means. The senator encouraged violent repression of Black voters by “red-blooded men” who could “keep the nigger from voting” by paying them visits the night before the election. It did not matter that in 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court had outlawed the “white primary,” conferring upon Blacks the legal right to register and vote. The on-the-ground reality in Mississippi did not match law on the books.

The Inc. Fund hoped to close the gap between social practices and legal ideals in the Magnolia State with the help of the state’s Black teachers. The case that Motley had come to try in Mississippi—part of a legal strategy unfolding in several other states—advanced a simple yet novel idea: that regardless of race, teachers and administrators with equivalent education and experience should be paid equally.

In Mississippi, Gladys Noel Bates, a Jackson science teacher and daughter of a local NAACP official, filed the lawsuit that attacked the school board’s practice of using different salary schedules for Blacks and whites. The case, known as Bates v. Batte, was brought on behalf of all Black teachers in Mississippi. It exemplified the discrimination that plagued teachers, the backbone of the middle-class Black community: even when they held superior credentials, Black teachers invariably earned less than their white colleagues.

As if the lawsuit itself were not enough of an affront to southern norms, LDF sent a co-counsel, Robert L. Carter, with Motley to Jackson. Not one but two Black lawyers from New York would invade the city, parade around the federal courthouse, sit at the counsel’s table, cross-examine witnesses, and attack the school board’s practice of assigning different values to the labor of Blacks and whites. The lawyers’ presence stunned whites and fascinated Black locals. “No blacks or women had ever appeared in the court before,” Motley recalled. The two—Carter, slim and bookish, and Motley, tall and stately—were a sight to behold.

Motley and Carter arrived in Jackson ten days before the trial started and spent an extended period observing and participating in the southern way of life. The experience of living in Mississippi, if only for a short while, enlightened and frightened Motley. The three-day trial took place in August, the Mississippi summer hot and humid.

Historically, more Blacks had lived in Mississippi—by 1860 the capital of the cotton-producing, slave-trading economy of the plantation South—than in any other state of the Union. Brought to the state to labor on plantations and in the cotton fields, Blacks had comprised half of the state’s population at the height of slavery and during the 1940s still constituted 40 percent. White planters constantly feared Black revolt, leading to the imposition of a brutally repressive racial regime, in a class by itself even by the standards of the Old South.

The Mississippi state constitution disenfranchised Black citizens, who lived under “Negro law,” a euphemism for the unequal application of laws, rules, and norms to African Americans. Law segregated them from whites in every imaginable sector of life. Sadistic racial violence—hanging, bludgeoning, dragging, drowning, dismemberment, and public burnings at so-called “Negro Barbecues”—and the threat of such brutality kept Blacks fearful and under white people’s social and economic control. This degradation and violence made Mississippi the “state that was the South at its worst,” according to a leading historian of the Magnolia State.

During her time in Jackson Motley observed the vestiges of slavery and the ills of segregation. At the same time, onlookers gazed at Motley, the well-dressed “nigra woman lawyer,” she recalled, as if she were a freak of nature. Never mind her occupation, Motley could not dine in the fine restaurants or sleep in the fine hotels on Capitol Street, even if they were far from the quality she had come to expect in New York. She and her co-counsel were relegated to a “rooming house” for blacks; “called a hotel,” the place barely passed for proper overnight accommodations.

Even food was hard to find. The white owners of a grocery store refused to sell fruit to the lawyers, one of whom called Carter—a thirty-two-year-old lawyer and military veteran who had vowed to destroy Jim Crow after chafing at white officers’ “raw, crude racism” in a segregated U.S. Army—a “boy.” Showing tremendous restraint, Carter held his tongue and defused the moment. “I felt Bob’s hand pulling me out of the door,” Motley remembered; incensed by the disrespect shown to her colleague, her first instinct was to defend Carter. He dissuaded her, saying, “Now, no point in getting upset when there is nothing we can do about it.” For sustenance, the lawyers relied on the few Blacks in the community who did not depend on whites for their livelihoods: the Black doctor, dentist, insurance agent, or undertaker who could bear the risk of inviting the New Yorkers into their homes for lunch or dinner. On other occasions the pair ate at a restaurant in the city’s Black commercial district. During those ten days in Jackson, Motley experienced the same racially charged indignities as her clients.

Once in court Motley realized that locals considered her first trial an event not to be missed. As a rule, Mississippi’s Black attorneys—there were only three—did not appear in court. They worked on legal matters, such as the drafting of wills and deeds, that did not disturb the racial order; when a case did call for a court appearance, white judges’ and juries’ hostility to Black lawyers demanded that litigants hire a white attorney to represent them. Motley and Carter’s very presence in the courtroom was transgressive: they were the first Black lawyers to appear in a Mississippi courtroom since Reconstruction. The sight of two Black lawyers, one female, transformed the court proceeding into a spectacle. Hordes came to see them perform. The standing-room-only courtroom overflowed. Blacks “lin[ed] the walls,” eager to bear witness to the attorneys’ unprecedented assault on white supremacy. Motley recollected that “it was like a circus” had come to town.

A first-time litigator in a new and hostile environment, Motley initially felt a “bit frightened.” Locals’ behavior justified her feeling ill at ease. The behavior of James Burns, one of the few Black lawyers in Mississippi and the Inc. Fund’s local counsel, stunned Motley. Burns aided the New York lawyers in only the most perfunctory manner, making his arm’s-length relationship to Motley and Carter clear to all. At the counsel’s table he sat far away from the Inc. Fund lawyers. He did not participate in the trial, but instead “took notes the whole time, never looking up.” And when he moved about the courtroom, Burns dramatically performed his subservience. He walked “completely bent at the waist,” his back “never to the judge” when he exited the courtroom. At the end of the day he rushed away and refused to dine with Motley and Carter. “He was scared to death,” Motley remembered. Burns’s fear put her on notice: the case she had come to Mississippi to litigate might provoke violent white resistance.

Motley did her best to ignore the racism of courthouse personnel. She felt anger but did not display it when the presiding federal judge, Sidney Mize, refused to call her “Mrs. Motley”; “Mrs.” was an honorific denied Black women, regardless of status, in southern society. Instead of showing her the respect that married white women received, local whites referred to her as “that Motley woman.” And she noticed a courthouse mural with “perfectly stereotypical” images. On one end appeared white women in hoop skirts escorted by white men in cutaway coats; on the other were Black men in work clothes and Black women in aprons beside bales of cotton, the cash crop of the plantation South, and symbols of Black bondage. Motley found the mural “emotionally agonizing,” but did not dare say anything about its prominent placement in the federal courthouse. She focused on the task at hand.

At trial Motley and Carter exposed the rank discrimination to which Jackson—and every other southern locale—subjected Black teachers and administrators. She called expert witnesses who demonstrated that Black teachers’ credentials compared favorably with and sometimes surpassed those of whites, and that even when Black teachers held notably better qualifications than their white colleagues, the school board paid them less. The pair “relentlessly” cross-examined witnesses whom the school board called to justify its policies and practices. The state’s witnesses squirmed. The LDF lawyers seemed to make headway in court. In fact, Motley dazzled many in the courtroom, who were “amazed” at the way she spoke. Even a court reporter praised her crisp questioning.

In the end, however, Judge Mize dashed Motley and Carter’s hopes of a win. The judge ruled against the lawyers on procedural grounds: he held that they needed to have “exhausted remedies” available in the Mississippi courts and administrative bodies before making claims in federal court.

___________________________________________________

From CIVIL RIGHTS QUEEN: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality by Tomiko Brown-Nagin. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright (c) 2022 by Tomiko Brown-Nagin.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Tomiko Brown-Nagin is Dean of Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School, and Professor of History at Harvard University’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. In 2019, she was appointed chair of the Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, of the American Philosophical Society, and of the American Law Institute, and a distinguished lecturer for the Organization of American Historians. Her previous book Courage to Dissent won the Bancroft Prize in 2011. She frequently appears as a commentator in media. She lives in Boston with her family.