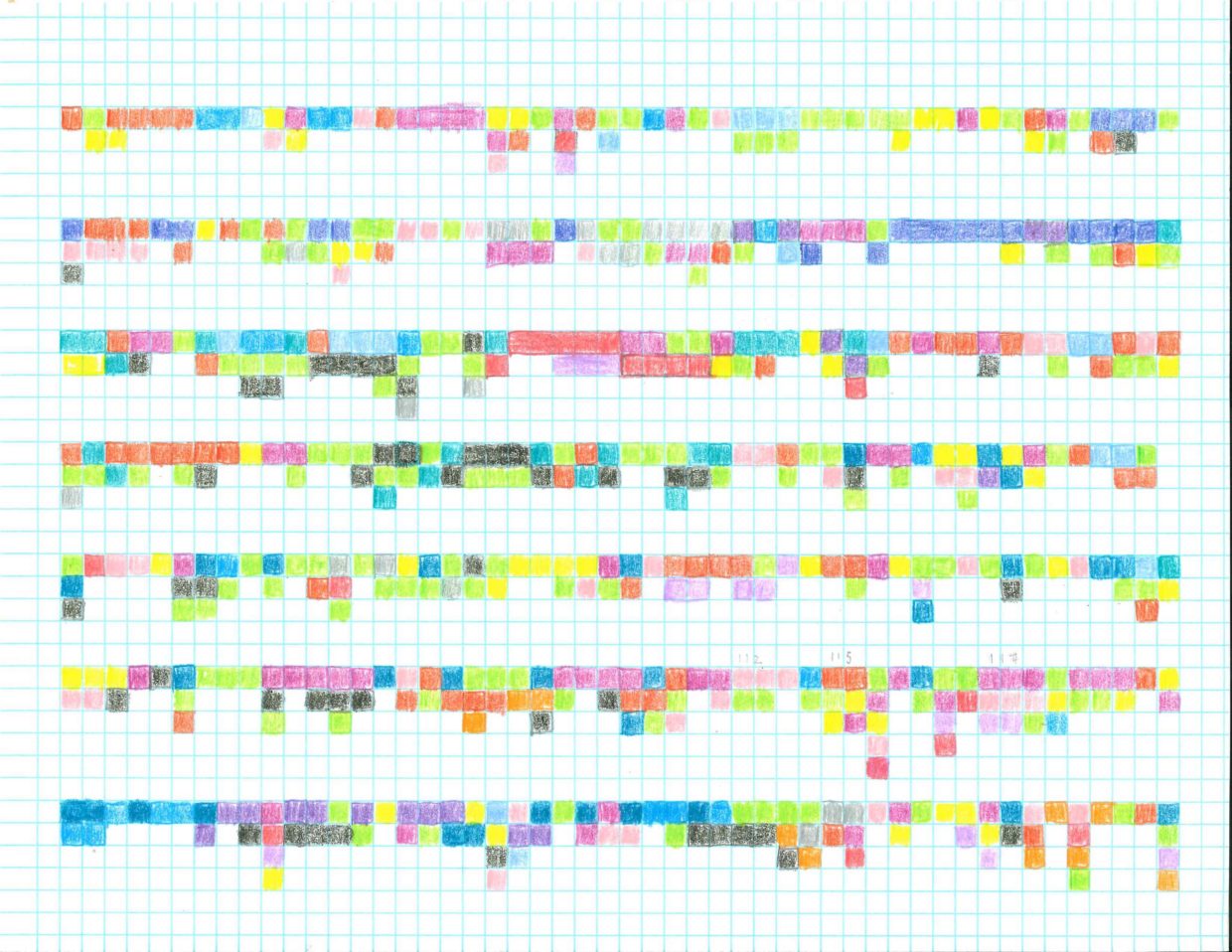

On the Patchwork Approach to Piecing Together a Book

Heather Christle Considers the Writing of The Crying Book

The last time I reached peak mathematical happiness was in tenth grade geometry. Equipped with graph paper, mechanical pencil, compass, and protractor, proofs seemed to glide from the ether directly to my hands. I was in a state of joyful calm, connected with a sense of immense capability.

I have the opposite feeling when I try to make what I write into a book. Once, having delayed the arrangement of poems into a recognizably manuscript-shaped order for as long as I could, I checked myself into a hotel room I couldn’t afford and told myself I wasn’t allowed to leave until I had finished. After hours of frustrated work, I left my pages slathered around the room and swam my body through the hotel pool.

So you can imagine the dread with which I approached the great mass of prose I’d typed over five years on the subject of crying, hoping to shape it into something that could be called The Crying Book. I had begun with a casual thought about what it would look like to make a map of every place I’d ever cried, believing I might be writing a prose poem. Then I read a little about the chemical composition of tears, how there are differences between those shed over onions and those shed in grief. That’s alright, I thought, it’s just an essay. People write essays. That’s fine.

Then I started reading and thinking about how parents in various cultures respond to their infants’ tears, and how white women’s tears can activate racist violence, and how professional mourners help those in grief remember how to cry, and meanwhile I got pregnant, and had a baby, and stopped sleeping, and then everything—my days, my reading, my body, my mind—grew so tear-drenched that I could no longer resist knowing the pages I was writing were a book.

Or rather, that a book was in there. But where were its edges? I knew its style and its form: brief prose vignettes, each with its own shape and integrity, but the larger pattern eluded me. I wanted a reader to find dual satisfaction, not only in each vignette, but in the way the book as a whole let them echo, develop, and turn in relation to one another. I tried and failed to hold it all in my mind at once, but no sooner had I grasped its centers around grief and the moon than singing and elephants would slip from the stack. And it all hurt to touch.

I had written, among the pages, the times I’d cried so much it felt death was the only route out, the times when the tears had told me terrible lies, that things could be no other way. I’d try to hold a paragraph in relation to another but the tug of each was so strong I’d land deep inside, unable to keep perspective, to see the whole.

I have thought about remapping the book, now that it is finished, to make the chart that would let me see the final pattern all stitched into place.

Still, I knew the whole was there, could sense the presence of its shape, even if it remained obscure to me. I thought of David Berman’s lines about “when you’re riding a mechanical bull and you strain to learn / the pattern so you don’t inadvertently resist it.” I thought about the quilter, Mensie Lee Pettway, who’s said of her work, “What I do is what they call ‘patchwork.’ I call it ‘this and that.’ I may start off looking like planning a ‘Nine Patch,’ but then I take this, take that, take patches, blocks, strips, and seeing where I am going, laying my pattern as I go.” I envied her ability to see the whole all at once, how one color, one shape calls out to another, though they may be stitched in at great distance. A quilt lets a pattern, a record of work made in time, be seen all at once in space. I longed for that view.

I remembered my mother’s quilt work, the graph paper on which she plotted her designs with colored pencils. I thought of John Sims’ MathArt quilts projects, in which he materializes “the square truth of connected stories.” I remembered the calm of the geometry classroom. I decided to try mapping my book onto that soothing blue grid. I borrowed my child’s colored pencils.

My editor had gone ahead of me, making numerical notes in the manuscript’s pages, coding its various strands. I went through and added more, but translating the numbers (and their corresponding subjects) into colors. Some choices were direct: the moon would be silver, whiteness an alarming vermilion. Others were happenstance, but came to feel essentially linked. Yes, science is yellow, yes, language and literature are green. The blue of autobiography deepened and lightened through time; periwinkle: I am young and my friend Bill is still alive; azure: Bill is gone and I am a mother.

I could see, at last, the whole, could see the gaps and oversaturation in the pattern. A long stretch of far too much purple, another where blue and I disappear. Happily, my new and colorful map corresponded with what my trusted readers were telling me: Why do you vanish here? Can you bring in more about crying behaviors later in the book?

What a relief it was to be able to hear those words and then move away from them, away from a sense of rhetoric and argument and rationalization. There were so many words already. What a joy to move away from the screen and back to paper, the place where all my writing work begins. What absolute satisfaction to smell the pencils; to hear the soft sound of a square filling up with orange; to look, in the end, at something that didn’t need time to be understood or experienced, that could be apprehended in an instant. I felt like I’d been pierced—painlessly!—through my skull by a compass, that I had only to turn and a perfect arc would take shape on the page. I went back to the screen, snipped and stitched over, deepened certain colors, embroidered for balance, found words on singing and crying whose shape fit perfectly in one corner’s jagged and empty space. I could see, finally, where I was going, how to make the pattern not rigidly symmetrical, not pretending to an overbearing and flattening totality or “universal” completeness, but whole nonetheless. The stitches would hold.

I have thought about remapping the book, now that it is finished, to make the chart that would let me see the final pattern all stitched into place. But I won’t. Why? In her essay, “A Sketch of the Past,” Virginia Woolf writes of “moments of being,” those brief instances in which a potent alertness breaks through the nondescript “cotton wool” of nonbeing that make up such a large part of one’s day. She describes one such instant from her childhood:

I was looking at the flower bed by the front door; “That is the whole,” I said. I was looking at a plant with a spread of leaves; and it seemed suddenly plain that the flower itself was a part of the earth; that a ring enclosed what was the flower; and that was the real flower; part earth; part flower.

The whole that I was able to apprehend through the process of filling in my chart is not the book, exactly, but the ring of all that enclosed it: the friends whose words gave me new patterns or new stitches to try, all that I had read and learned, the years of work and mothering, the many sentences I’d written—needed to write—and needed just as much to let fall away. The chart gave me an ability to perceive all of this at once, the whole: “part earth; part flower.” I cannot contain this whole in one book, but I can stitch my patchwork together in such a way that—when activated by the brightness of a reader’s mind—they create together their own new whole, their own moments of being.

—————————————

Excerpted from The Crying Book by Heather Christle. Used with the permission of the publisher, Catapult. Copyright © 2019 by Heather Christle.

Heather Christle

Heather Christle is the author of the poetry collections The Difficult Farm; The Trees The Trees, which won the Believer Poetry Award; What Is Amazing; and Heliopause. Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, London Review of Books, Poetry, and many other journals. She teaches creative writing at Emory University in Atlanta. The Crying Book is her first book of nonfiction.