On the Monumental, Lasting Impact of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympic Games

John Feinstein Considers the History of Racial Inequality and Activism in Sports

The case can be made that Tommie Smith and John Carlos, his Olympic teammate in Mexico City 43 years ago, started the Black Lives Matter movement 42 years before anyone actually heard the term. Back then, it was called civil rights. Smith and Carlos, both graduates of San José State University, were mentored there by Professor Harry Edwards and competed in track and field events. They were among a group of Black athletes who considered boycotting those 1968 Olympic games for several reasons, including the potential participation of South Africa and Rhodesia. Another reason was the continued presence of Avery Brundage as chairman of the International Olympic Committee.

At a pre-Olympics meeting in Denver, shortly before the games were to begin, the athletes decided against a boycott.

“Instead,” Smith said, “we decided that it was up to each of us to figure out how we wanted to make our voices heard. I knew if I did nothing, there would be no chance to make any progress. I couldn’t do nothing.”

Smith and Carlos had never been teammates; Carlos had transferred into San José State when Smith was a senior and had to sit out that season. But they knew each other, frequently trained together, and had often competed against each other. Smith had been the world record holder in the 200 meters until Carlos had unofficially broken his record earlier in 1968. Carlos’s record wasn’t officially recognized, because he was wearing a shoe that had not yet been approved for competition.

On the night of October 15, 1968, Smith pulled away from Carlos going around the turn in the 200 and sprinted to victory in a world record time of 19.83. Carlos was also passed in the final meters by Australian Peter Norman, who won the silver medal in 20.06—still the fastest time, even in 2021, ever run by an Australian. Carlos won the bronze medal.

What happened next has been the subject of books, documentaries, and debate for more than 53 years. While the three medalists waited for the medal ceremony to start, Smith pulled out two black gloves. The plan had been for each man to wear a pair of gloves, but Carlos had forgotten to bring his gloves. It was Norman who suggested each man wear one glove. Smith handed the left one to Carlos. “I wanted the right one because I’m right-handed,” he said, laughing at the memory many years later.

He and Carlos took off their running shoes and put on black socks. The absence of shoes was to symbolize the poverty that so many Black people dealt with in the United States. The two men also placed buttons on their USA uniforms. The buttons read OPHR, which stood for Olympic Project for Human Rights.

The OPHR, the group that had considered the Olympic boycott, had made three demands before the Olympics: that Rhodesia and South Africa be barred from the games because of their apartheid (racial separation) policies; that Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight title—stripped from him when he refused to be drafted—be restored; and that Avery Brundage step down as chairman of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for decisions he had made in a previous era.

As chairman of what was then the American Olympic Committee, in 1936, Brundage had given in to German “requests” that Jesse Owens, the four-time gold medalist, not be introduced to Adolf Hitler. Beyond that, Brundage had removed two Jewish sprinters from the US 4 × 100 relay team so as not to offend Hitler.

That act turned out to be as life-changing for Norman as it was for the two Americans.

Rhodesia and South Africa were barred from the Mexico City games—although the IOC claimed that the decision had nothing to do with the demands of the OPHR but instead came about because the presence of the two countries would “inject politics” into the nonpolitical Olympics. Brundage remained in power, however, to the regret of Smith, Carlos, the OPHR movement, and, as it turned out, the entire Olympic movement.

While they waited to be called to the podium, Norman asked Smith and Carlos what the OPHR buttons were. When they told him, he asked if they had one he could wear. They didn’t, but before the ceremony began, Norman found Paul Hoffman, the coxswain for the American eight-man rowing team, who was in the stadium. Hoffman had one of the buttons and happily gave one to Norman. Soon after, the three men walked back into the stadium for the medal ceremony. That act turned out to be as life-changing for Norman as it was for the two Americans.

The medals were presented. The three men turned in the direction of their country’s flags as the “Star-Spangled Banner” was played. Smith and Carlos, each now gloved, bowed their heads and raised their arms to the sky, fists clenched. The photo of the two of them, with Norman standing in front of Smith, arms at his side, is one of the most iconic ever taken.

“It’s been 53 years, and I feel like I’m still being asked to make the same argument over and over.” John Carlos was talking in short, almost breathless bursts. He’s 76 now and doesn’t give a lot of interviews—especially to people he knows nothing about. But he had agreed to get on the phone with me to hear why I wanted to talk with him for this book. The truth is, I never got to ask a question. Once I got through with my explanation, he began talking.

“Look at what just went on in Washington,” he said—this was shortly after the attempted insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. “What do you think that was about? Race! What do you think would have happened if that had been a Black Lives Matter rally and it had turned into that kind of a riot and they had tried to attack the Capitol? You know what would have happened? There would have been hundreds dead and a lot of white people screaming they got what they deserved.

“This has been going on for more than four hundred years in this country, hasn’t it? When Tommie and I did what we did, we were called every name in the book. We were thrown out of the Olympic movement. And you know what? There are still plenty of people out there who think we got what we deserved—just like there are people out there today who think that kid [Colin] Kaepernick got what he deserved.

“He sacrificed his career doing what he thought was right. He wasn’t any different than Tommie and me. And the response wasn’t all that different either, was it?”

Smith and Carlos were, in fact, banned from the Olympic movement and ordered to fly home from Mexico City by—you guessed it—Brundage. They were also ordered to return their medals.

“Never did it,” Smith said. “They told me a time and place to go to, to surrender my medal. I just never went.” Neither did Carlos.

The backlash against Smith and Carlos by white America, indeed by many in the mostly white media at the time, was perhaps best summed up by a column written by Brent Musburger, then a young columnist working for the Chicago American.

“Smith and Carlos looked like a couple of black-skinned storm troopers, holding aloft their black-gloved hands during the playing of the national anthem,” Musburger wrote. “They sprinkled their protest with black track shoes and black scarfs and black power medals. It’s destined to go down as one of the most unsubtle protests in the history of protests.”

“It’s been 53 years, and I feel like I’m still being asked to make the same argument over and over.”

Smith and Carlos wore black socks—no shoes—on the medal stand. Their so-called black power medals were the OPHR pins—one of which was also worn by Norman. Musburger never did explain why a protest should not be “unsubtle.”

“But you have to give Smith and Carlos credit for one thing,” Musburger continued. “They knew how to deliver whatever it was they were trying to deliver on international television, thus ensuring maximum embarrassment for the country that is picking up the tab for their room and board here in Mexico City. One gets a little tired of the United States getting run down by athletes who are enjoying themselves at the expense of their country.”

This was 1968, not 1858. Musburger could easily have been a plantation owner who couldn’t understand why his “darkies” were complaining about working 12 hours a day in the cotton fields when, after all, he fed and housed them.

The US Olympic Committee (USOC) wasn’t “picking up the tab” for the Olympic athletes—who in those days were paid nothing for competing—out of the goodness of its heart. It was picking up the tab in return for the athletes’ bringing glory to the American flag by bringing home medals to the good old USA.

Musburger went on to become an iconic TV broadcaster, first with CBS and then with ABC and ESPN, known mostly for his “You are looking live!” openings at games. He retired from ESPN in 2017 so that he and his son could run their own gambling business in Las Vegas, but he has continued to do radio work for the Las Vegas Raiders into his eighties.

In 2017, a year after Kaepernick had started the anthem protests, which had been continued by many of his former teammates in San Francisco, Musburger tweeted at one point: “Yo #49ers, since you instigated protest 2 wins and 19 losses. How about taking your next knee in the other team’s end zone.”

Musburger has never publicly apologized for the 1968 column even though there have been many stories urging him to do so. Carlos says he has no interest in even discussing Musburger other than to say, “He was proven wrong.”

When I began conducting research for this book, I reached out to Musburger, who I’ve known for about 35 years. I sent him a text detailing the book and asking if he and I could speak about the column. He responded quickly, sending me a photo taken a few years ago in Las Vegas. It was a photo of him, Raiders owner Mark Davis, and Tommie Smith.

He offered no explanation of the photo other than to say that the three of them had eaten dinner together. I wrote back and said, “This makes me want to talk to you about this even more.” He responded by saying how much he respected Smith’s mother. He never responded to my request for an interview other than to say my bringing up the events of 1968 had made him think it was time for him to write his autobiography.

Later, when I spoke to Smith, I asked about the meeting and the photo.

“Mark Davis is a friend,” he said, “and he asked if I would be willing to get together with him [Musburger] for dinner one night. I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ To be honest, I was curious what he might have to say. When I asked him what he was thinking when he wrote the column, he went on about how young he was [29] and how he had to write the column that way because that was what his bosses wanted him to do.

“He said, ‘I had to do it to protect my job, to take care of my family. I had to do it.’ I waited for him to say ‘I’m sorry.’ Instead, he came over to me and started crying, put his arms around me and said, ‘I had to do it, I had to do it.’ He never actually apologized, but I still felt sorry for him at that moment. Not for what he did, but for the fact that he had to know how wrong he’d been. To me, the tears were his apology, but he never actually said ‘I’m sorry.’

“He knew the column was racist; he had to know it. He just couldn’t bring himself to say it.”

While Musburger’s column came to symbolize the reaction of much of the white media, there were columnists who defended Smith and Carlos and were outraged by Brundage’s decision to throw them out of the so-called Olympic movement.

In a twist, the person who may have suffered the longest because of what happened that night was Norman —the Australian silver medalist. When Smith and Carlos told him what they planned to do, Norman, who had fought against the “White Australia” policy in his home country that had limited immigration by nonwhite people (sound familiar?) said he would support them in any way possible.

“When we told him [Norman] what we were going to do,” Carlos said, “we thought we’d see fear. Instead, all we saw was love—and support.”

That was when Norman found Hoffman. Later, the IOC actually threatened to sanction Hoffman for giving Norman the pin that he had worn on the medal stand.

“I wish there were more people in our country willing to stand up the same way Peter did.”

Because of that show of support for the two Americans by wearing an OPHR pin, Norman was pilloried in his home country for years. In 1972, even though he had bettered the required Olympic qualifying time in the 200 meters on 13 occasions (and the qualifying time in the 100 meters five times), he was left off the Olympic team after finishing third in the 200 at the Australian Athletics championships. Running with an injury, Norman went 21.6—well above the qualifying time of 20.9 and considerably slower than the Australian record time of 20.06 he had run in Mexico City.

The Australian Olympic Committee had the option of adding Norman to the team because he had met the qualifying standard in both the 200 and the 100 multiple times. The committee opted not to send him to Munich. In 2000, when Sydney was the host city for the Olympics, Norman was not invited to the games by the committee. The excuse was that it would be too expensive to invite all Australian Olympians. Norman was given the opportunity to buy tickets. But the committee failed to mention that Norman wasn’t just an Olympian; he was a silver medalist and still held the national record in the 200.

Instead, Norman went to Sydney as a guest of the USOC. Brundage, who died in 1975, no doubt rolled over angrily in his grave.

The three men who stood on the podium together in Mexico City remained friends until Norman died of a heart attack in 2006 at the age of 64. Norman had flown to San José in 2005 to be part of the unveiling of a statue on the San José State campus honoring Smith and Carlos. The statue, 22 feet high, depicts Smith and Carlos with fists raised on the first- and third-place medal platforms. The second platform is empty. Norman asked that it be left empty so that visitors to the statue could stand on his empty spot to feel as if they had joined Smith and Carlos in their protest.

When Norman died, Smith and Carlos flew to Australia to eulogize him at the funeral and to be pallbearers.

“He was my brother,” Carlos said at the time. The USOC declared the day of the funeral to be Peter Norman Day, the first time it had ever made such a declaration for a non-American athlete.

In his eulogy, Carlos said, “Peter Norman was a man who knew that right could never be wrong. Go and tell your children the story of Peter Norman.”

Although the Australian Olympic Committee clung to the myth that Norman’s actions in Mexico City had not been punished in any way, the Australian Parliament finally issued a formal posthumous apology to Norman and his family in 2012.

There were four items in the official statement.

This House recognizes the extraordinary athletic achievements of the late Peter Norman…

Acknowledges the bravery of Peter Norman in donning an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on the podium, in solidarity with African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos who gave the “Black Power” salute.

Apologizes to Peter Norman for the treatment he received upon his return to Australia and the failure to recognize his inspirational role before his untimely death in 2006 and

…Belatedly recognizes the powerful role Peter Norman played in furthering racial equality.

To say that the apology was too little, too late is an understatement. Norman lived the last 38 years of his life under a cloud in his home country because he had the courage to support Smith and Carlos. He had been dead for six years before the parliament got around to admitting the Olympic Committee had been lying for years about its treatment of Norman.

“The sad thing is I knew—knew—that wearing the button wasn’t going to be a good thing for Peter that night,” Smith said. “The way the world was then, a white guy standing up for two Black guys, two scary Black guys, wasn’t going to turn out well. But I admired him for doing it. I loved him for doing it. Right then and there, he did a lot to bridge the gap between Black and white. I wish there were more people in our country willing to stand up the same way Peter did.”

Smith and Carlos were the lead pallbearers at Norman’s funeral; Carlos on the left, Smith on the right. “That was the heaviest coffin I ever carried,” Smith said. “Physically and emotionally.”

Norman didn’t live long enough to hear the apology read in the Australian Parliament. Smith and Carlos have become heroes to many—if not most—in the United States. In addition to the statue at their alma mater, both have received honorary PhDs. And in 2019—51 years after Mexico City—they were inducted into the USOPC (US Olympic & Paralympic Committee) Hall of Fame. It took the USOPC even longer than it took the Australian Parliament to get around to trying to right the wrongs of men like Brundage and Musburger.

A year earlier, Smith and Carlos were asked by USA Track and Field to present the Jesse Owens Award for 2018 to sprinter Noah Lyles. They were introduced—via video—by Colin Kaepernick. The standing ovation was long and loud.

The torch had been passed.

__________________________________

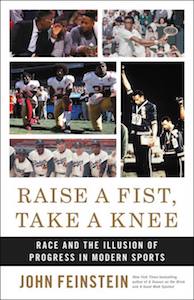

Excerpted from Raise a Fist, Take a Knee: Race and the Illusion of Progress in Modern Sports. Used with the permission of the publisher, Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2021 by John Feinstein.

John Feinstein

John Feinstein is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of the classic sports books A Season on the Brink and A Good Walk Spoiled, along with many other bestsellers including The Legends Club and Where Nobody Knows Your Name. He currently writes for The Washington Post and Golf Digest and is a regular contributor to the Golf Channel, Comcast Sports Regional Networks, and he hosts a college basketball show and a golf show on SiriusXM Radio. The Back Roads to March is now out from Doubleday.