On the Meteoric Rise of “Aunt Elsie,” Beloved Newswoman and Children’s Columnist

“I don’t believe in hammering in morals. I just believe in telling children’s stories which will make them happy.”

A teaser for her first column ran in the Oakland Tribune on December 19, 1918, under the headline “Kiddies, Look Here!” She was introduced as both Elsinore Crowell and “Aunt Elsie”—a woman who could talk to animals and “share all their secrets.”

“I don’t believe in hammering in morals,” she stated. “I just believe in telling children’s stories which will make them happy.”

Her column, “Trestle Glen Secrets,” named after a wooded area near Lake Merritt in downtown Oakland, hit the paper on Sunday, December 22. It ran adjacent to Frank Baum’s far more prominent column, “The Wonderful Stories of Oz,” a series based on his popular second book, The Marvelous Land of Oz. Using the same intimate, animated voice of the stories she published in John Martin’s Letters, she wrote and illustrated a tender-hearted tale of a group of animal friends—Jimmy Squirrel, Mattie Mud Hen, Billy Owl—who come to the rescue of two orphaned mice siblings on Christmas Day.

The story was a hit and fan mail from kids poured into the Oakland Tribune’s mail department from kids across the city.

Based on the enthusiastic response, and coinciding with Baum’s death, Levy expanded Elsie’s column. On May 11, 1919, she was given a weekly, one-page feature called Aunt Elsie’s Magazine for the Kiddies of the Oakland Tribune. In 1920, he shortened the title to Aunt Elsie’s Magazine and expanded her feature to two pages. And in 1922, Levy assigned Elsie an entire section—a whopping eight pages—for her juvenile stories.

She wrote separate sections for children based on their ages, including thrillers that played out over several installments for older readers and cartoons and crafts for younger kids. One week’s handicraft included directions for how to make a camp stove from an empty can of tomato juice; another included cutouts to design an elegant paper wardrobe for a clothespin doll.

Elsie encouraged her young readers to write to her at the “Tribune House” and promised to write them back.

“Tell me about the happys—and tell me about the sads,” she wrote in her “Jewel Box” column for girls. “Because I had sads too, little girl. If you don’t want me to print the sad letter in the paper, send me a stamped envelope with your address on it and I will write you a letter all your very own that will make you know that my arm is around you and that I love you very much.”

Now with a stable paycheck, one of the first purchases she made was a cheap tweed suit. Too cheap, it soon ripped in the derriere—as George her son gleefully pointed out one afternoon when she returned home. No matter. She ripped out one of the pockets and fashioned it into a patch before joyfully returning to the throngs of professional women striding down Market Street.

“Tell me about the happys—and tell me about the sads,” she wrote in her “Jewel Box” column for girls. “Because I had sads too, little girl.”

Her success kept growing. Her columns were passed from child to child, and “Aunt Elsie” clubs, sponsored by the Tribune, formed across Northern California with thousands of members. At one point, there were chartered Aunt Elsie clubs in sixty-five towns—ranging from Redding, 200 miles to the north of Oakland, to Monterey, 120 miles to the south, to Nevada City, 140 miles to the east—covering a territory far larger than the Tribune’s distribution.

Children received membership cards that entitled bearers to “ALL THE GOOD TIMES AND PRIVILEGES” of the club and proudly wore membership pins featuring an enamel red heart against a white background with the words “Aunt Elsie Club Member” around it. Club members organized parades for which they built ornate floats and wore costumes indicating their favorite section of the magazine—the Witches’ Cave (for girls) or Pirates’ Den (for boys). They competed in drawing and short story writing contests for the chance to have their work published in the paper.

The Tribune began to host Aunt Elsie parties in an assembly hall on the top floor of the Tribune Building and stage variety shows at local venues. These events were so popular that the Oakland Police Department dispatched officers for crowd control.

“One, two, three, four blocks of kiddies! Count ’em! Stretching clear around the American Theater block, everyone grinning, waiting in the sunshine for the show to begin,” ran a feature about one such event in the Oakland Tribune on April 9, 1922. The price of admission was “a cheerful smile,” and entertainment included song-and-dance revues by the Tribune Juveniles performance troupe, screenings of (silent) movies—and, of course, heavily applauded appearances by the lady of the hour herself.

Aunt Elsie’s tremendous success even triggered a blatant rip-off: On July 2, the San Francisco Chronicle launched “The Chronicle Kiddies Corner” featuring “Aunt Dolly.” Children were invited to write letters to Aunt Dolly, join the Chronicle Kiddies Club, and submit their own stories for possible inclusion in the paper. The column’s introductory message contained familiar hype: “Aunt Dolly will arrange theater parties for her Chronicle Kiddies’ Club—when they’ll see new films and plays and leading playhouses—absolutely free.”

As Elsie’s fame shot up among the school-age set, parents began to read the comforting words she offered their children, and before long, they also began to write to Elsie, seeking advice for their own quandaries.

Bored, bewildered, often embittered by the chaotic times, Mother and Dad wanted to talk things over with somebody in the know… The unconventional style of the Aunt Elsie work put them at ease. So Mother and Dad began writing in, asking what, why and whither.

The Tribune, seeing an opportunity to expand its circulation, assigned Elsie a homemaking column called “Curtains, Collars, and Cutlets: Cheer-Up Column.” The section ran with her own name as the byline, “Elsie Robinson.” Before long, the title was shortened to “Cheer-Up” and the scope expanded to attract male readers. She’d often add her own illustrations, signing them “ERC” or “ER.”

In 1920, she began writing a second adult column, “Cry on Geraldine’s Shoulder”—with Elsie as “Geraldine”—which focused on relationship problems.

“Is your one wife too many?” she asked in an announcement for the new column. “Is your husband or your complexion growing dull? Let us then discuss the value of soft soap on complexions—and husbands… We shall sit together on the edge of the world. You have wanted a friend. I’M IT.”

When Elsie landed in the news business, she did so by building on the fame and success of women writers who preceded her. This included stunt reporter Nellie Bly, who in the late 1880s, wrote accounts of her voluntary confinement in one of New York’s most notorious insane asylums and the fictional hero of author Jules Verne’s book, Around the World in 80 Days (she did it in seventy-two).

Around 1900, newspaper editors began to hire female reporters to write human interest stories, believing women wrote more “emotional” copy than men—noting such details as, say, the tears in a widow’s eyes or her trembling hand. Subsequently derided as “sob sisters,” the highly sentimental writing style of these reporters went out of vogue by the 1910s—yet these journalists paved the way for future generations of newswomen like Elsie.

___________________________________

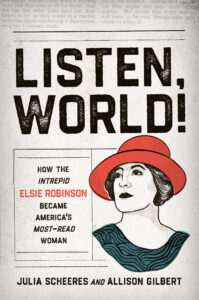

Excerpted from Listen, World! How the Intrepid Elsie Robinson America’s Most-Read Woman by Julia Scheers and Allison Gilbert. Copyright © 2022. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Julia Scheeres and Allison Gilbert

Julia Scheeres is the author of the New York Times–bestselling memoir Jesus Land and the award-winning A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Jonestown. She lives in Northern California. Allison Gilbert is an award-winning journalist and author of numerous books including Passed and Present and Parentless Parents. She lives outside New York City.