On the Long, Lonely Apprenticeship of the Writing Life

Kayla Min Andrews Remembers Her Mother, Author Katherine Min

“You might want to buckle down. It’s a looooooong apprenticeship.”

–Mom

*Article continues after advertisement

Sometimes people ask me, “What was it like, having a fiction writer as a mom?”

Sometimes people ask, “Is that why you write fiction, too?”

Let me answer with a snapshot from 2009:

I am twenty-three. I am waitressing at a Chinese restaurant in a suburb of New Orleans. I have no idea what I want to do in life, but I love to read, and once in a while, I write down a scene of something that happened at the restaurant. Then I either forget about it, or send it to Mom with an email that says something like: Well, I was bored today, so I took some notes. Here they are.

One day, Mom calls me.

“I liked your story,” she says.

“Oh, it’s not a story. I was just—”

“I think you’re a writer,” she says, her tone insistent and amused. She is teasing me. Because she’s said this before and I’ve denied it.

“I was just bored at work, Mom,” I say with mock exasperation.

“But you know,” she adds, “you might want to buckle down. It’s a looooooooong apprenticeship.”

I change the subject. In my infinite wisdom, I wait another decade before taking her advice.

*

I encountered the phrase “long apprenticeship” again recently, while reading Charles Baxter’s fantastic craft book Wonderlands. He describes how, as a young man, he wrote three novels which, according to him, absolutely no one liked, until finally getting his first book accepted for publication.

I’ve gotten better at accepting that failure is inevitable in any life worth living.

This reminded me of my friend Maurice Carlos Ruffin, who speaks openly and generously about his two unpublished novel attempts, written before his debut We Cast a Shadow. Which reminded me of something Julia Phillips said at a writer’s conference about an ambitiously structured novel that she wrote before her bestselling debut Disappearing Earth.

I realized many authors have “apprenticeship novels”—novels written before the author’s published debut, which don’t get published but which help the author grow. Novels the author now agrees should never have been published. Novels the author has no desire to revisit. It’s not for the faint of heart: pouring huge amounts of time and energy into writing that might never end up on anyone’s shelves. But in today’s frenetic, time-optimizing, productivity-worshiping culture, there’s something beautiful to me about the patience and commitment of the apprenticeship novel.

And so my thoughts, as thoughts about writing often do, take me back to Mom.

*

I grew up in a small town in central New Hampshire. Though Mom was clear in her identity as a fiction writer, she worked a full-time job as a staff writer for the local university’s alumni magazine. She’d come home from work at 4:30pm every weekday, say hello and goodbye to the babysitter (until my brother and I grew old enough to watch ourselves after school), change into pajamas and read me a few chapters of whatever novel we were currently reading aloud together—advancing from Roald Dahl and Charlotte’s Web to Virginia Woolf and Crime and Punishment over the years. After reading, she’d take a nap, then stumble groggily downstairs to watch Oprah or Entertainment Tonight before making dinner. She wrote on weekends and holidays and at occasional artist residencies.

Her parents and extended family grumbled about her disappointing career, thwarted in their desire to brag about her to their friends. Mom didn’t care. She kept writing fiction. “I’m a late bloomer,” she’d say with a shrug and a devious, knife-sharpening smile.

According to the rough count of my memory, she wrote four novels, one screenplay, and one young adult novella throughout my childhood, none of which were published. This was her period of loooooooong apprenticeship. Not only did she write and write, she also pursued honest feedback on her writing from a variety of sources. She took classes and workshops, engaged with a wide community of writers she met at residencies and conferences, submitted to literary journals, applied for writing grants, queried agents.

The feedback helped her grow and improve. It helped her recognize when she was on the right track. Over the course of my childhood, she progressed slowly from never-published to a few publications (her first short story was accepted in the late 1980s, by a now-defunct magazine designed for dentists’ waiting rooms!) to publishing in well-regarded journals like Ploughshares and winning a Pushcart Prize for her story “Courting a Monk.” She landed an agent who stuck with her for many years before she ever got a book deal.

Only now, in my thirties, after her death, can I understand two things. That she pursued success in a way I deeply admire, her strategy hinging on persistence and feedback. And that her success was never assured.

Plenty of talented writers don’t get book deals. The market is fickle and crass; publishing decisions are often based on factors beyond a writer’s control. I didn’t feel the terror of these odds as a kid because I believed in Mom unquestioningly. I saw her as she saw herself: a brilliant artist who hadn’t yet published a book but would, probably soon, probably whichever novel she was currently working on. My nuclear family—Mom, Dad, my brother, and me—lived inside this dream together. The dream started before I was born, and came true when I was eighteen.

*

As I was getting ready to leave home for college, Mom was finishing up her novel Secondhand World. “This is the best thing I’ve ever written, and if it doesn’t get published, that’s it, I’m done with writing,” she said in a moment of frustration.

This pronouncement terrified me. It had never occurred to me, in all my eighteen years, that she might give up on the dream. I couldn’t imagine her not writing. I went off to college uneasy.

At some point during my freshman year, she called to say that Secondhand World had been accepted for publication. By Knopf! Of course it was, I thought, as I squealed a surprised congratulations into the phone. Of course it was.

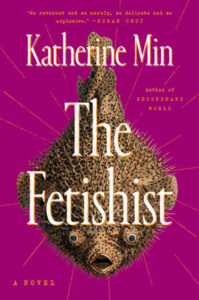

The publication of her debut novel in 2006 changed Mom’s life. She was able to get tenure at a teaching job she loved. She was able to take sabbaticals to spend more time writing. She started working on a new novel, a darkly funny thriller/love story called The Fetishist. (Which, as it turned out, would be published posthumously.)

*

Mom’s death, in 2019, finally jolted me to acknowledge what I think on some level I’d always known: Stories excite me like nothing else, and I want to write them. Death can be clarifying. It can cut the bullshit out of inner monologues.

Mom’s life taught me that the process centers on persistence and feedback.

Are you happy with your life, big picture? I asked myself sometimes, sitting by Mom’s bed in the hospice center while she slept.

No, I’d answer. Haven’t been for a long time.

What might change that?

Writing.

Well, okay then.

And that’s how I started to write in earnest. By which I mean: I buckled down.

Once, in the hospice center, her mind fuzzy from cancer and painkillers, Mom asked me, “What’s death like?” in a trusting child-like voice.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“I hope they let me write about it,” she said dreamily.

It wasn’t publication or accolades or being remembered that occupied her mind at the end. It was the desire to create.

Now, here I am: at the beginning of my looong apprenticeship. There is terror in knowing that the novel I’m working on now—my first—might never be published. Or the one after it. Or the one after that.

I used to be so afraid of failure I pretended I didn’t care about writing. I’ve gotten better at accepting that failure is inevitable in any life worth living. Though the deeper truth is apprenticeship novels aren’t failure. They’re part of the process. They are simply a part that doesn’t get turned directly into a product.

One of the many lines from The Fetishist that haunts me is this one, about a young punk rocker: “She liked to make things—music, art, video—but once she was done, she lost interest. It was the process that mattered, the making; the product was incidental. In this, she was a true artist.”

With this line, and with this character more broadly, I think Mom was dramatizing and exaggerating an aspect of herself. In reality, Mom saw value in promoting her work as a product—she did such tasks diligently, from finding an agent to organizing a DIY book tour for Secondhand World. But deep in her idealistic heart, and part of what made her such a compelling person, was a fierce love of the process—not the product—of creating.

Mom’s life taught me that the process centers on persistence and feedback. You struggle to create something. Then you seek honest feedback from others. You figure out which bits of feedback require you to change and grow so you can improve what you’ve made, or make something better next time. Then you struggle to create again. It’s a good outline for life in general: struggle to do something, get feedback, struggle to do it better. The process—more than publication, money, or acclaim—interests me. (Though, to be clear, those things interest me, too.) The process makes me feel alive.

These days, I sometimes smile as I imagine looking up from my laptop to answer Mom’s comment of fourteen years ago:

“You might want to buckle down. It’s a looooong apprenticeship.”

“I know, Mom. I am now. Thank you for your advice, and your example.”

__________________________________

The Fetishist by Katherine Min is available from G.P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Kayla Min Andrews

Kayla Min Andrews is a biracial, Korean American writer living in New Orleans. She has a piece forthcoming from The Massachusetts Review and has been published in Cagibi, Halfway Down the Stairs, and Asymptote. Her flash essay “Old Kleenex” was nominated for a Best of the Net 2020. Kayla assisted Putnam on the posthumous publication of her mother’s novel The Fetishist (January 2024), including editing the manuscript and writing the afterword. Kayla is an MFA candidate in fiction at Randolph and is working on a novel.