On the Literary Roots of Die Hard

Nick de Semlyen Traces the Road from Nothing Lasts Forever to "Yippee-ki-yay, motherf*cker"

Die Hard had started with a man named Roderick going to see a movie in 1975. Novelist Roderick Thorp, a burly, bald former private investigator best known for his novel The Detective, bought a ticket for The Towering Inferno, sat through 165 minutes of Paul Newman and Steve McQueen trying to save a large ensemble cast of tanned celebrities, and then went home and had a horrific nightmare.

Just as the image of a Terminator rising from flames first came to James Cameron in a bad dream, so Thorpe that night imagined a lone figure trapped in a high-rise, fleeing men with guns. He expanded the image into a 1979 sequel to The Detective, Nothing Lasts Forever, in which a retired NYPD officer named Joe Leland has a very bad Christmas Eve inside the forty-story headquarters of a company called Klaxon Oil. After battling ten invading German terrorists, he drops their leader, Anton Gruber, out of a window, though his daughter dies in the process, too.

It got good reviews, with the Miami Herald even anticipating the inevitable big-screen adaptation (“Nothing Lasts Forever is truly a one-man show that would require an actor of Sinatra’s stature to do it justice”) and saluting the cleanness of its high concept (“The building is sealed off; the gang is in an impregnable position, except for Leland, the one-man army, who hides on the top floors above them”).

Yet the book would bounce around Hollywood for most of a decade without drawing much interest. Finally a young executive named Lloyd Levin, who worked for Lawrence Gordon, discovered and began championing it. Gordon brought in screen-writer Jeb Stuart. And over two and a half months, Stuart turned Thorpe’s dense first-person prose, which featured its hero monologuing at length on CB radio and offering long sections of exposition about Klaxon Oil’s sideline in arms dealing, into a screenplay.

“I worked with what Bruce was,” says McTiernan. “We had to work out: what are the circumstances in which you can like this man?”Much changed, starting with the title. Where Nothing Lasts Forever conjured up images of a James Bond movie or Rock Hudson melodrama, Die Hard left little doubt as to what to expect. At John McTiernan’s behest, the ten terrorists became ten thieves masquerading as terrorists; it would allow them to shake off the novel’s fug of solemnity and make it a caper instead. The earnest dialogue and flat supporting characters became similarly zesty, even more so once Steven de Souza was brought in for a pass.

And then there was the hero, no longer Joe Leland but John McClane (it had been “John Ford” in early drafts, after Stuart saw a mural of the Westerns director on the Fox lot). Stuart had already made him younger than his sixty-year old literary equivalent, but originally envisioned him as suave and sophisticated, with a slick sports coat. This would have worked for Richard Gere, but once the un-suave Bruce Willis was official, McClane was retooled all over again. “I worked with what Bruce was,” says McTiernan. “We had to work out: what are the circumstances in which you can like this man?”

Overhauling the script, they leaned into Willis’s working-class roots—in his pre-acting days he had been a truck driver and a security guard at a nuclear power plant—and his man-of-the-people charm, honed while working as a bartender in New York, famous for his bone-dry martinis and signature cocktail, Honey I’m Home (the ingredients for which Willis has never divulged).

McClane would now begin the movie by declining an invitation to sit in the back of a limousine, getting in the front with the driver instead. He wears a white A-shirt under his flannel shirt, like a stevedore. And beneath the bravado, the grins, the “Yippee-ki-yay, mother-fucker,” is a guy who’s scared shitless.

McTiernan, who saw Die Hard as akin to William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (albeit with fewer fairies and more C- 4), envisioned McClane as a wounded soul. “The secret is that he doesn’t like himself,” the director says. “He thinks he’s a loser. His wife thinks he’s a loser. And he’s just doing the best he can. He’s being a smartass to rise above the pain. And Bruce being a smartass in that circumstance becomes an act of heroism. The audience can like him for it.” Adds de Souza: “Vulnerability became a feature, not a bug.”

And as the hero changed, so did the villain. A generic heavy was transformed into the polar opposite of a beat cop: designer suit, superior sneer, citations from Plutarch (“Benefits of a classical education”). Hans Gruber—Anton no more—was becoming an action-movie equivalent of the arrogant, expensively dressed bankers to whom Willis once served martinis. Albeit, thanks to the casting of Alan Rickman and the citrus-sharp dialogue, Gruber was a villain so fun that you’d actually want him to walk away with $640 million in bearer bonds, if it weren’t for the guy in the A shirt.

“It’s like that cartoon about the mouse looking at the eagle and giving him the finger,” McTiernan says, summing up the two opposing forces. And on November 2, 1987, the mouse and the eagle entered Nakatomi Plaza for the first time.

__________________________

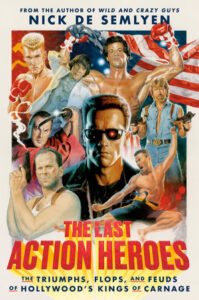

Excerpted from THE LAST ACTION HEROES by Nick de Semlyen Copyright © 2023 by Nick de Semlyen. Excerpted by permission of Crown. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.