On the Liberation Struggles of the

Soviet Refuseniks

Natan Sharansky Recalls the Global Effort to Get Russian Jews to Israel

After I broke out of the ivory tower of doublethink, I became a free person living in an unfree land. I knew I was joining a struggle with no guarantee of a happy ending. I was sure, however, that my life would be filled with a sense of purpose, a feeling of belonging, and the blessings of freedom—even if I never reached the free world. What I didn’t know was that I would get a special bonus. Very quickly, I found myself in the center of one of the most exciting—and challenging—movements in Jewish history.

I grew up in a world where Jewish solidarity was only expressed through coded hints and secret nods. I went to a school where I could not even acknowledge I was considering moving to Israel with the select group of roommates who huddled around the radio with me at night, secretly listening to Voice of America.

Then, suddenly, within a few weeks, I found myself openly, overly connected to Jews. In joining the struggle, I entered an exhilarating, exhausting world that attached me to my fellow Soviet Jews, Israelis, and Jews from communities across the globe in the least secretive, most exposed way.

The struggle to save Soviet Jewry was unique. It was global, involving Jewish communities on both sides of the Iron Curtain. It was pluralistic, mobilizing French Communists and British aristocrats, pious rabbis and assimilating lawyers, American patriots and Zionist activists, countercultural hippies and Establishment leaders. And it was focused. Everyone wanted to rip a hole in the Iron Curtain to free millions of Jews. The shared mission came down to three Hebrew words: shlach et ami, let my people go.

*

As with every totalitarian regime, the Soviet Union’s rigidity caused great instability. It was as vulnerable as a big man highly allergic to a small bee. Trying to control everything ultimately meant that any deviation, no matter how small, could threaten everything. Ever fearful that its obedient armies of doublethinkers were about to turn into dissidents, the regime could not permit its citizens to decide what to read or what to say. Recognizing the mass desertions open borders could cause, it also couldn’t allow its citizens to choose where to live. That’s why this command-and-control society had no official procedure for emigration.

There was only one legal way out: pleading family reunification. Most people, however, feared admitting they had relatives abroad. Beyond that, applying for a visa set you on a bureaucratic obstacle course with little chance of success. The conditions were so daunting that the authorities assumed few would dare to start the process.

That is why the Jews’ post–Six Day War identity awakening surprised the Soviets. Suddenly, dozens, hundreds, then thousands of once-quiescent Jews proclaimed they wanted to leave. Exploiting the family reunification loophole, Israeli officials helped every Jew interested in immigrating find Israeli “relatives” to certify their relationship and their pressing desire to reunite.

Feeling threatened, the regime pushed back, cautiously. In the 1950s, it would have been simple: anyone suspected of such criminal thinking would have faced immediate arrest and possible execution. But by the 1970s, the Communist elites didn’t want a Stalinist bloodbath. Looking inward, they learned that all this purging and mass murdering was too risky for them; today’s killer became tomorrow’s kill too easily.

Looking outward, the Soviet Union, desperate for the West to help its failing economy, was now pretending to respect international norms. As the regime tried, in Andrei Sakharov’s words, to follow in the Western ski tracks economically, it became vulnerable to Western pressure politically.

Deprived of serious Jewish educations, most of us Refuseniks were just discovering our roots.

The counterattack against Soviet Jewry, approved at the highest level, followed a two-part strategy. By letting a limited number of Jews reunite with their families, the Communist system pretended to be humanitarian to impress the West. At the same time, the regime prosecuted some Jewish activists in show trials while refusing the visa requests en masse. Soviet Jews understood the thuggish message: anyone starting this emigration process could lose everything for no clear gain.

Today, the word Refusenik describes young Israelis who refuse to serve in the army, babies whose birth mothers refused to take them home from the hospital, and even teenagers refused service at a bar despite their fake IDs. Half a century ago, a modest Russian language teacher from London, Michael Sherbourne, coined the term to describe the class of people in the purgatory these new Soviet tactics created. Michael’s single word describing those refused permission to emigrate by the Soviet authorities became a global brand. Eventually, tens of thousands of Refuseniks were denied their right to emigrate.

The label took on a deeper meaning for a tiny subset, who resisted the regime’s diktats twice: first, by applying for visas and then by refusing to accept the refusal silently. Particularly inspired by the events of August 6th, 1969, when members of 18 Georgian Jewish families appealed to the United Nations for help to leave the Soviet Union, Refuseniks protested in the streets, circulated petitions worldwide, and became the voice of Soviet Jewry. The number of activists ready to confront the authorities rarely exceeded 200. In all my years of organizing petitions, I don’t recall ever collecting more than 130 signatures.

Deprived of serious Jewish educations, most of us Refuseniks were just discovering our roots. In breaking through from doublethink to dissent, we also broke into the storehouse of Jewish history. We developed a sweeping narrative that reflected our activist passion more than any scholarly erudition. Our appeals often connected our cause with the chain of Jewish freedom fighters we knew: from the exodus from Egypt, to the Maccabees in ancient Judea, to the founders of Zionism and the pioneers of modern Israel.

The Soviets tried jamming the Refusenik message systematically. The authorities staged press conferences starring Jewish mathematicians, scientists, writers, chess players, and ballerinas—some of whom were world-famous. All issued carefully rehearsed statements affirming how happy they were in the Soviet paradise. But the world wasn’t fooled. These official Jews were obviously doublethinkers mouthing Soviet propaganda.

By contrast, the words of a few Jews, far less famous, were more sincere. The world took the small band of Refuseniks—who had the chutzpah to speak in the name of three million silenced Jews—very seriously. Having abandoned the life of Soviet lies, Refuseniks said what they—and most Soviet Jews—really thought.

Moscow’s show trials in 1970 and 1971 against Jewish activists also backfired. They catalyzed global protests. The burgeoning international movement earned one of its first big victories when the regime commuted two death sentences imposed in December 1970, following the first Leningrad trial. The Soviet retreat demonstrated a new sensitivity to world public opinion and a vulnerability to the movement, encouraging even more activism.

But, no matter how loud, the small group of Soviet Jewish Refuseniks could never have survived alone. From day to day, even minute to minute, our struggle only worked because we joined a broader struggle for Jewish freedom. While Jews and non-Jews from all over the world eventually helped, Israel’s contribution to the cause was unparalleled, symbolically and practically.

The state’s founding in 1948—and its fight to survive in 1967—triggered the Soviet Jewry movement. Israel was determined to reach out to Jews behind the Iron Curtain. After all, this is why Zionists founded the Jewish State. Saving them was such a priority that, starting in 1951, a secretive organization to advance these goals operated out of the Israeli prime minister’s office.

Officially given a misleadingly bland name—Lishkat Hakesher, the Liaison Office—Nativ was headed from 1970 to 1980 by Nehemiah Levanon. Levanon was so formidable that we activists whispered his name in awe. A devoted Zionist and kibbutznik, a character straight out of a Zionist novel, Levanon led his colleagues in harnessing Israel’s state power to assist the Soviet Jewish campaign.

They collected whatever information they could about Soviet Jews, even in the 1950s, when the Iron Curtain seemed impenetrable. They sent thousands of tourists over the years to encourage Refuseniks, executed complicated diplomatic maneuvers, and choreographed the emigration process, finding “relatives” whenever necessary.

Golda Meir’s devotion to Soviet Jewry made her the “mother of the movement.” By 1969, this Ukrainian-born, American-educated Labor Party leader (and Israel’s first ambassador to the Soviet Union) was Israel’s prime minister. No matter how busy she was, she regularly met planes landing in Israel with Soviet immigrants. “I’m not just welcoming these newcomers,” she said. “I’m doing it for them,” meaning those of us still stuck in the USSR. “I want Soviet Jews to know they are important to us.”

Zionism meant that a country thousands of miles away, which most Soviet Jews had never visited, would never stop fighting for us; Israel made that far-fetched idea appear normal. The best example of how far Israel would go to save Jews occurred on July 4th, 1976. That night, 100 Israeli commandos secretly flew over 2,500 miles to Entebbe, Uganda, refueling in the air, to rescue 12 Air France crew members and 94 Jewish passengers—mostly Israeli—whose plane had been hijacked by pro-Palestinian terrorists.

Elie Wiesel became the living link connecting the horrors of the Holocaust, the bounty of America, and the biggest Jewish community still in distress.

Soviet Jews considered this successful operation a personal message from Israel. As soon as I could find a photo of the martyred commander of Entebbe, Yoni Netanyahu, I hung it on my wall. Later, throughout my years in prison, whenever I heard a plane flying overhead, my pulse quickened, reminding me that Israel and the Jewish people would never, ever abandon me, or us.

The global network of the Jewish people amplified the Refusenik voice, and our power. A new generation of Jews arose. Most felt comfortable as free, increasingly prosperous citizens in the West. They were often empowered by the courageous New Jew in the Middle East. But their defiant cry of “never again” was tinged with guilt. They were vowing to avoid another mass failure, of free Jews not doing everything possible to save endangered Jews.

Elie Wiesel became the living link connecting the horrors of the Holocaust, the bounty of America, and the biggest Jewish community still in distress, Soviet Jewry. Wiesel first traveled to the Soviet Union in 1965 as a journalist from the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. The Jewish despair he encountered shocked him, 20 years after his liberation from the Buchenwald concentration camp.

His 1966 book The Jews of Silence challenged the world to speak up about our isolation. This modern prophet shamed many American Jews into action. Later, for all his achievements as a novelist, Holocaust memoirist, human rights activist, entrancing lecturer, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Wiesel told me he hoped to be most remembered for giving voice to the millions of Jews living behind the Iron Curtain.

Thanks to Wiesel and others, news about the Soviet “Jews of silence” spread throughout the Jewish world in the 1960s. Committees formed. Organizations developed. In 1971, organizations from across the ideological spectrum gathered in Belgium. Overcoming many deep differences, the 800 delegates at the first Brussels conference agreed on one central idea: let my people go. This Jewish human rights movement became an international cause célèbre, one of history’s most successful human rights campaigns.

Jews of the free world lobbied their leaders as concerned outsiders and, occasionally, as political insiders. Tourists to Russia—who didn’t tour much—became the living bridges between Refuseniks and the outside world. They kept coming, no matter how many KGB informers masquerading as Intourist guides menaced them. They kept calling, no matter how many telephone lines the KGB cut. They created a global communications network, updating Soviet Jews and others by dialing the phone and handing off mail, person-to-person, decades before the Internet’s invention.

Characteristically, Jews followed many different paths to visit us in Moscow or fight Moscow with us. Some activists, vowing “never again,” were Jews born on American soil, embarrassed that their sha-shtil, don’t-rock-the-boat immigrant parents and grandparents did nothing while six million died during the Holocaust. Some, shouting “Freedom now,” were civil rights activists applying the skills they had mastered in Alabama and Mississippi to help their people in a human rights struggle. Some, singing “Am Yisrael Chai” and proclaiming, “We are one,” were Orthodox Jews or Zionists acting on their values as Jewish nationalists.

But, above all, the Soviet legal demands framed it nicely: it was a worldwide family reunification project. One branch of my family, the Lantsevitskys, had arrived in Canada decades earlier, before World War I. All contact was cut off for years. When my case was in the news, the family patriarch, Noah, said, “This guy must be related to us. We used to be Shcharanskys too.”

When they contacted Avital, it turned out to be true. The family, now the Landises, plunged in, helping the struggle in so many ways, from hosting Avital to recruiting others to fight. Irwin Cotler, my Canada-based attorney, used my newfound Canadian connection to convince Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau that Canada had a real stake in freeing me, beyond the broader human rights fight. In the grand sweep of the struggle, this was just one more relatively minor episode. But for me, the symbolism was very significant. After decades of distance, Soviet and Western Jews were rediscovering that we were all part of one big extended family.

Some tourists came well briefed by Israelis or Jewish organizations. Others were acting independently. Whatever their motives, whatever their level of involvement, we in Moscow were often surprised by how committed these strangers were to our cause.

Once, I gave a young woman from Philadelphia a copy of a letter one hundred Refuseniks had signed. She was going to smuggle it in her underwear out of Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport. She would deliver it to a Jewish organization, which would then pass it on to one of our champions, Henry Jackson, a non-Jewish Democratic senator from Washington, a state with few Jews. Watching her fold up the letter, noticing how hard she was trying to mask her nervousness, I felt badly for her. “Don’t do it, if it makes you feel uncomfortable,” I said. “We can always find other ways, by telephone or diplomatic pouch.”

Echoing something hundreds of tourists said over the years, she explained, “No, you don’t understand. I’m not doing you a favor. You’re doing me a favor. You’re changing our lives. You’re letting us make Jewish history together with you.”

By promising “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms,” the Soviet Union had settled the debate and signed its ideological death warrant.

The free, cushy lives of American Jewish baby boomers couldn’t have been more different than our unfree, severe existence. Many of them were drifting away from the Jewish identity we were running toward. Suddenly, we shared the common thrill of rejoining Jewish history and changing it together. Decades later, one American Jewish leader told me, “You Refuseniks saved my generation from assimilation.”

The Soviet authorities dismissed the movement as a fly-by-night annoyance. KGB officers mocked this “bunch of hooligans,” who would soon get distracted by some newer, sexier headline-making cause. Indeed, more Diaspora Jewish activists were bankers than bomb throwers. Few in power expected that these commonplace crusaders, leading a global grassroots movement, would be so persistent—fighting for decades, sometimes passing the responsibility like a family heirloom from activist parents to activist children.

The authorities couldn’t control the problem. Like water leaking into a basement, it threatened their very foundation. As mass refusals and show trials failed to discourage Jewish visa applicants, the Soviets experimented with more sweeping restrictions. In August 1972, they imposed an “education tax.” Anyone who benefited from the Soviet Union’s free higher education had to pay retroactive tuition before emigrating.

This is the kind of Soviet Trojan horse that would have tricked earlier generations of Western dupes, especially because, in this case, Americans were used to paying big money to send their kids to college. But by now, most Westerners had learned to look for the ugly reality behind the decorative Communist façade, thanks to the Refuseniks’ coaching. The fees the Soviets assessed were almost one hundred times the average monthly salary, in a world where few people had any savings.

The charade and the repression backfired again. The free world was proving equally inventive and responsive. The outrage over the education tax helped build support for the Jackson-Vanik amendment to the Trade Act of 1974 in the US Congress. Just as the Soviet Union was about to reap the fruits of its new policy of détente toward the West and gain economically beneficial most-favored-nation trade status from the United States, Senator Henry Jackson and Congressman Charles Vanik stepped in, making these economic benefits contingent on the regime granting freedom of emigration.

Henry Jackson’s linkage of American foreign relations to human rights concerns was controversial. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wanted to advance détente with no strings attached. The debate intensified during negotiations over the Helsinki Accords in 1975. Few realized that, by signing the seventh clause promising “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms,” the Soviet Union had settled the debate and signed its ideological death warrant.

The Soviet Jewish movement’s grand coalition, cooperating with other dissident groups, had pressured diplomats into injecting human rights considerations into all dimensions of the Soviet Union’s relationship with the West. From lonely demonstrations in New York and London during the mid-1960s to the December 1987 march on Washington, mobilizing a quarter of a million people, there was one clear message: Jews throughout the world—with cherished allies—would not stop demanding that the Soviets “let my people go.”

This global coalition, spearheaded by Israel, continued demanding our freedom into the 1990s. In December 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. By then, more than two million Jews were on the move. More than one million ultimately arrived in Israel.

__________________________________

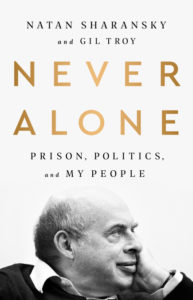

Excerpted from Never Alone: Prison, Politics, and My People by Natan Sharansky and Gil Troy, Copyright © 2020. Available from Public Affairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc

Natan Sharansky and Gil Troy

Natan Sharansky lives in Jerusalem with his wife Avital. He has two daughters and six grandchildren.

A native of Queens, New York, Gil Troy is currently Professor of History at McGill University. He is the author of several books, including Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s and Hillary Rodham Clinton: Polarizing First Lady.