On the I Ching as a Writing Guide

How the Ancient Chinese Divination Text Helped Heinz Insu Fenkl Write His Novel

Many Western artists and writers have been inspired by the I Ching. The Beat poets, like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs, were known to use it as a tool to access the subconscious and the collective unconscious. The composer John Cage used it as a way to generate randomness and chance in his compositions, giving them their distinctive and often remarkable qualities. Probably best-known to contemporary readers is the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick, who consulted the I Ching as part of writing The Man in the High Castle.

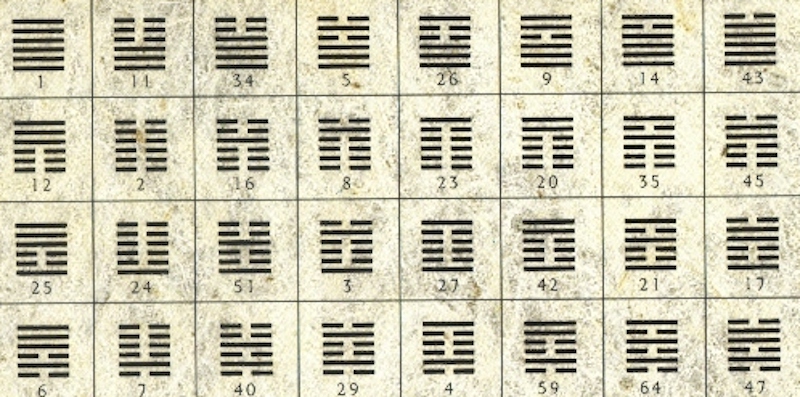

Also known as The Book of Changes, the I Ching, is an ancient Chinese divination text that has been used for thousands of years for guidance on personal, philosophical, and political questions. Its origins are mythic, attributed to Fu Xi, a wise ruler who lived 5,000 years ago and is said to have been half serpent. Each of the 64 hexagrams that comprise the I Ching represents a different dynamic state of being, and by studying the meanings of the hexagrams and the relationships between them, one gains a deeper understanding of one’s place in the ever-changing flux of the cosmos. For a writer, especially when looking for motivation, consulting the I Ching can provide valuable insight.

In writing my novel, Skull Water, I used an archaic consultation method I learned from my mother’s eldest brother (my “big uncle” in Korean) who is the basis for the character Big Uncle. His method was a pictographic one based primarily on the Zhoui Yi, the ancient Chinese text that is the foundation of the I Ching. The Zhou Yi is a collection of short oracle texts that were used to consult the gods and spirits, without the extensive commentaries that came later.

For a writer, especially when looking for motivation, consulting the I Ching can provide valuable insight.

Big Uncle was a geomancer, someone who could read the spiritual energy of a landscape and locate auspicious sites for graves and houses. When I was little, I often watched him mumbling under his breath and scratching what I thought were stick figures and random lines in the dirt. Afterwards, he would make confident pronouncements about what he was going to do. I knew he was performing some sort of ritual, but when I asked, he would just say it was “nothing” or “a secret.” It wasn’t until I was in graduate school doing a tutorial in Classical Chinese that I realized Big Uncle was consulting the I Ching by using pictograms, the oldest form of Chinese writing.

In my novel, the story of Big Uncle’s survival during the opening months of the Korean War in 1950 runs parallel to the story of Insu’s quest for the legendary skull water, which is set in the mid 1970s. Because the novel is so much about the interconnections between the two characters and the convergence of their lives, I was looking for a way to make those parallel story lines resonate without having to use too much exposition.

Because the novel is autobiographical, I also wanted a way to stimulate my memory of my own teenage years while also reflecting on Big Uncle’s adventures, which are based the things he and my other relatives had told me about the war years. Since I had already been studying the I Ching for many years by then, consulting it in the traditional way, I wondered what would happen if I tried Big Uncle’s unique method and made that an integral part of writing the novel. I had already written parts of Skull Water, but when I incorporated Big Uncle’s method of consulting the I Ching, the result was quite remarkable. I wrote 400 pages from September to January. At times, I was focused simply on describing the images that were flooding my mind in a kind of autohypnosis.

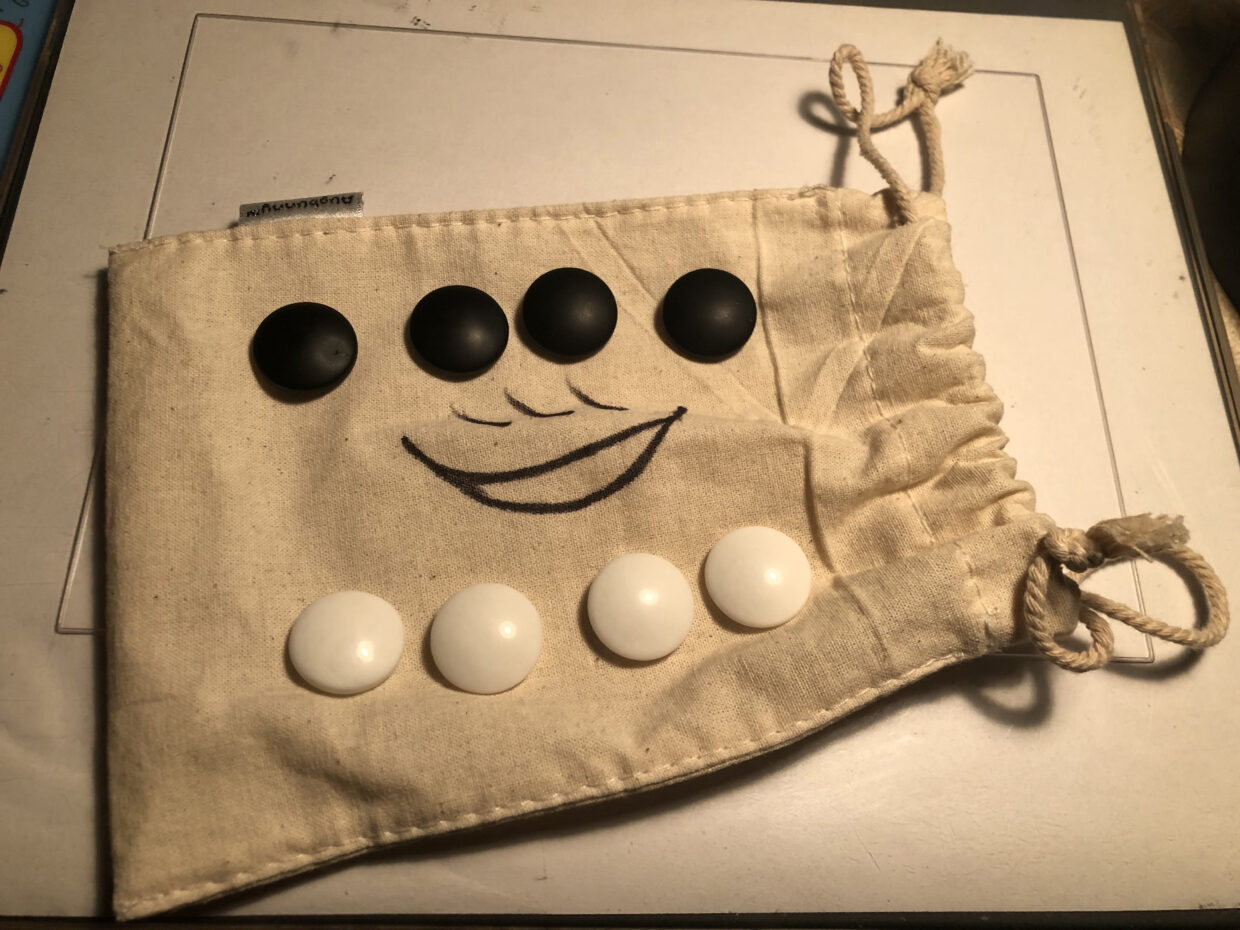

My cloth pouch with its four black and four white baduk (go) stones, the method Big Uncle used for his readings.

My cloth pouch with its four black and four white baduk (go) stones, the method Big Uncle used for his readings.

I tend to think of good novels not so much as texts but as places one can enter in one’s imagination, and because my Big Uncle was a geomancer, I approached my own novel as a kind of literary landscape. As I consulted the oracle, I asked for auspicious “landmarks” in the form of the pictograms, and the ones I received functioned as guideposts or, sometimes, almost like billboards. Initially, I would frame a question like “What should I write today to resolve the theme of returning in the rest of this chapter?” But as I became more familiar with the process and the results, my questions became simple requests like “Give me a pictogram for this passage.”

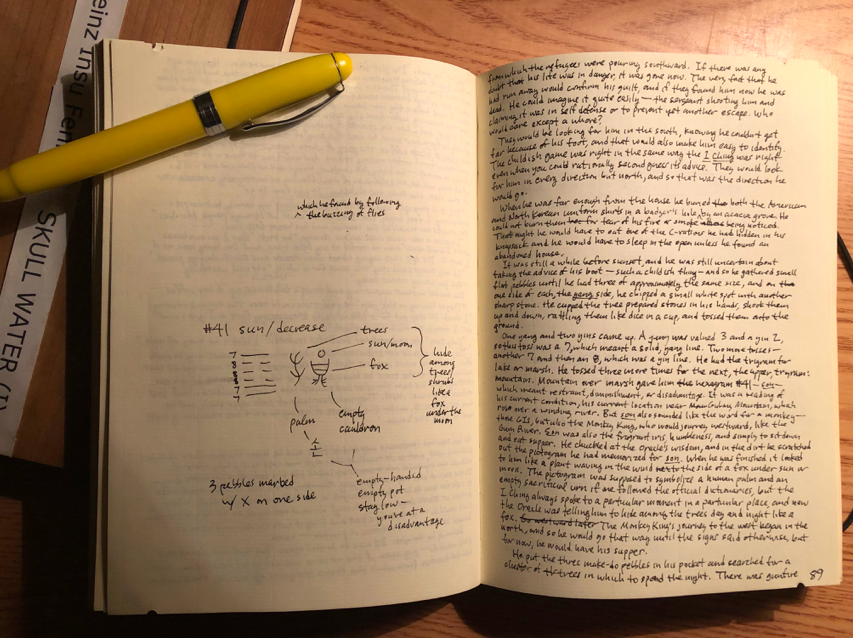

An example from one of my two Skull Water notebooks. The hexagrams and pictograms, with my notes, are on the left and the handwritten draft of the novel is on the right.

An example from one of my two Skull Water notebooks. The hexagrams and pictograms, with my notes, are on the left and the handwritten draft of the novel is on the right.

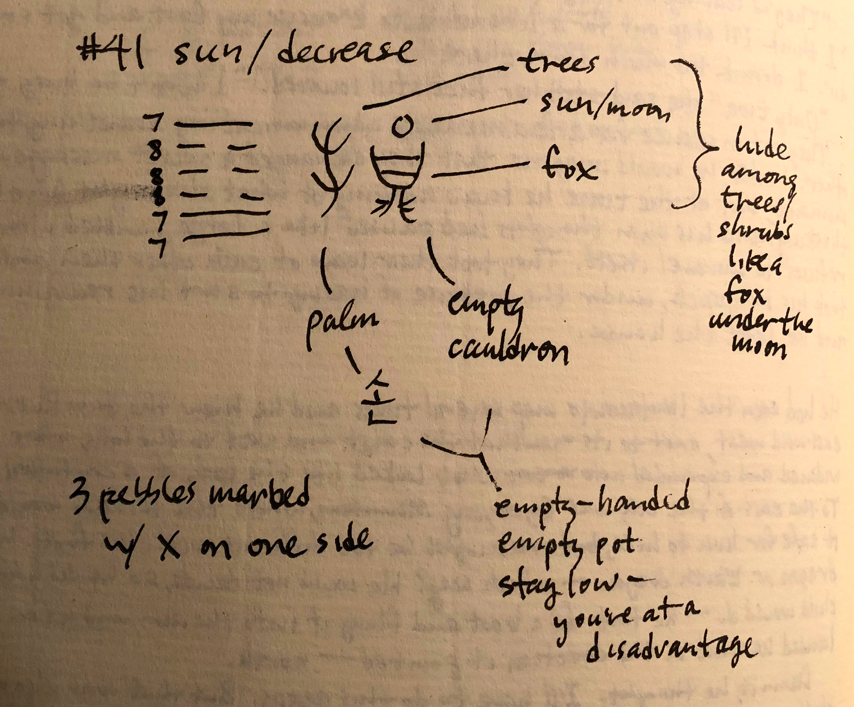

The image above is of a passage in which I incorporated an I Ching reading directly into with scene it produced: Big Uncle does an I Ching reading. You can see the hexagrams, the pictograms, and my initial associations on the left-hand side from the reading I did before writing the passage. In the accompanying text, Big Uncle casts the hexagrams, draws the pictograms, and interprets them much in the same way—my reading provided the specific descriptive details for the action in the story. Big Uncle hides like a fox among the trees. He uses stones to consult the oracle, and he hides something in a badger hole by a tree under the sun. I looked up the textual reading in the Wilhelm/Baynes edition of the I Ching (which is the best translation) and found this key verse: “Thus the superior man controls his anger / And restrains his instinct.”

Enhanced detail of the I Ching reading.

Enhanced detail of the I Ching reading.

Big Uncle has just escaped a dangerous situation, in fear of his life, and was forced to leave behind someone he loves. He is certainly angry and—given that it is wartime—his first “instinct” is simply to run. He must restrain that impulse and do something calm, rational, and strategic in order to survive. He has to hide, day and night (i.e., under sun and moon), in the woods. The figure on the right side of the pictogram looked vaguely like a rucksack to me, but also sort of like a wide-jawed insect eating something so, in the passage, Big Uncle finds a can of C-rations in his rucksack and eats them.

When you consult the I Ching, the answer you get—and the way you resonate with it—happens from a unique vantage point in time, place, and consciousness. Do not waste this precious insight.

Keep in mind that there was no conscious plotting or formulation of the passage before I wrote it. I did not pause after the reading from the I Ching. I went immediately to writing what felt intuitively right. Some of the details in the passage had to be cut in the final edits because of length, but the central actions and descriptive details are in the final text of the novel and the scene as a whole not only works where it is—it also resonates with earlier details and foreshadows what comes later in Big Uncle’s journey, which is resolved only at the very end of the novel. Because plot is not the action, per se, but the meaning that links actions, using the I Ching also integrated the plot in an unusual way, connecting events in keeping with one of the important underlying themes in Skull Water: karma.

If you look up the etymology of the two pictograms, you will see that they differ from the direct pictographic reading. The “official” reading of the pictogram on the right is two hands and the figure on the right is an empty cauldron (a sacrificial vessel). That reading would suggest that Big Uncle had to or has to sacrifice something to do the right thing, and in the story, he actually has. He has sacrificed his relationship to the woman with whom he was falling in love.

Could I have plotted the scene and come up with the same details without using the I Ching? Probably. But it would have taken much longer and required a great deal of revision later to create the same kinds of resonances forward and backward in time. It would have involved more trial and error and second guessing, and even then, the result might have been too obtrusive when done consciously. Using the I Ching, I was able to write a scene that would normally have taken me three or four times as long. I was able to write over 100,000 words in five months, and for writing literary fiction, that is the most productive I have ever been.

When you consult the I Ching, the answer you get—and the way you resonate with it—happens from a unique vantage point in time, place, and consciousness. Do not waste this precious insight. The oracle does not tell you what to do—it lays out the terrain so you can see where you have been and where it is possible to go. The ultimate decision and action are up to you. Do the right thing.

_______________________________________

Skull Water by Heinz Insu Fenkl is available now via Spiegel and Grau.

Heinz Insu Fenkl

Born in South Korea to a German father and a Korean mother, Heinz Insu Fenkl grew up in Korea until he was twelve and then in Germany and the United States. A professor of English at The State University of New York, New Paltz, he is known internationally for his collection of Korean folktales and translations of contemporary Korean fiction and classical Buddhist texts. He is also the author of the novel Memories of My Ghost Brother, a PEN/Hemingway Award finalist and a Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” selection. An excerpt from Skull Water, “Five Arrows,” was first published in the New Yorker. Fenkl lives in the Hudson Valley with his wife and daughter.