On the Greatest Speech of Jesse

Jackson’s Life

David Masciotra Revisits the 1988 Democratic Convention

Jesse Jackson began his address at the 1988 Democratic Convention by introducing the audience to Rosa Parks. Raising her hand in the air, and smiling wide and bright, he christened her the “mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” “Those of us here think we are sitting, but we are standing on the shoulders of giants,” Jackson declared before reciting the names of whites, blacks, Christians, Jews, and atheists who died, from bullets flying into their bodies, knife wounds, and brutal beatings to make American democracy credible, and the rainbow coalition possible, with their work in the civil rights movement.

National political conventions were once the settings of political combat and backroom calculation. In an unpredictable, and often unmoored, display of infighting, approximate in sight and sound to the floor of New York Stock Exchange, party delegates would actually select their presidential and vice presidential nominees at the convention. John Kennedy, for example, fought, lobbied, and brokered deals in order to have his name in the VP slot on the Adlai Stevenson ticket of 1956. He fell short, but did not accept his defeat until mere minutes before the delegate count. Gore Vidal depicted the high energy and intrigue of past conventions with his play about the battle for a presidential nomination, The Best Man.

In the 1970s, due to the healthy shift in emphasis from party elites to primary voters in nomination power, conventions became little more than expensive celebrations of the hosting party. Rather than capturing the intricate machinations of realpolitik, they began to resemble cheerleading exhibitions in which the greatest reward awaited the speaker or presenter who could wave his pom-poms and perform cartwheels with the most enthusiasm. For Jackson to begin his speech, not with a triumphalist tribute to the Democratic Party, but a reminder of the bloodbath and body count that was necessary for America to construct a genuine democracy signaled a different theory and practice of convention oratory.

“My audience was not those on the convention floor” Jackson told me, “It was those watching on television who never got involved in party politics before—the outsiders, the marginalized, the first time voters our campaign brought into things.” Jackson had an hour on primetime television. He was not about to waste it on the bromides of bumper sticker slogans. The address was an electric and emotional hybrid of populist advocacy for a left turn in American politics, but also a fiery homily on the secular rewards of faith, and the human spirit’s capacity to overcome the catastrophes of fate and the cruelties of man. Jackson weaved together political logic and data supportive of his political claims, but when he sang and shouted in sermonic delivery, he relied upon the evidence of his own experience. Transforming the Omni Coliseum of Atlanta, Georgia, into a Pentecostal temple, he gave a testimony.

Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis was reportedly nervous about allowing Jackson to speak at the convention. “When he gets through,” the candidate told a journalist in tones of consternation, “none of us will be able to meet that standard.” Writing in the New York Times, a paper previously unfriendly to Jackson’s presidential campaign, veteran columnist E. J. Dionne claimed that Jackson’s “rousing” performance “did nothing to dim Dukasis’ prediction.”

*

The prophet, according to popular misinterpretation, is a clairvoyant who might accurately identify tomorrow’s winning lottery numbers, or prevent a child from running across the street because she can envision an inevitable hit and run. Theology and history offers a much richer understanding of the term “prophecy,” and makes clear that it is not synonymous with psychic power. Abraham Joshua Heschel, the rabbi who became a close friend and supporter of Dr. King, explained in his book, The Prophets, that the prophet does not speak for God; he reminds his audience of “God’s voice for the voiceless.” Heschel’s theological interpretation submits that “prophecy is the voice that God has lent to the silent agony, a voice to the plundered poor, to the profane riches of the world.”

Jackson weaved together political logic and data supportive of his political claims, but when he sang and shouted in sermonic delivery, he relied upon the evidence of his own experience.

Theologian and religious historian, Richard Lischer, writes in The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word that Moved America that in ancient Israel there were two forms of prophets—central prophets and peripheral prophets. Those on the periphery moved among the poor, gave unsparing and scathing denunciations of power, and never obtained access to the monarchy. Central prophets advised and consulted with kings, struggling valiantly to persuade them to serve the will of the people and keep their covenant with God. King, according to Lischer’s analysis, spent the last years of his life as a peripheral prophet, especially as his message and mission became increasingly radical. When he met with President John Kennedy, and later President Lyndon Johnson, to discuss civil rights legislation, however, he was a central prophet. Jackson never amassed the official influence of King, but with the success of his presidential campaigns, he began to move from the margins to the center.

Heschel writes that he chose to rigorously study the ancient prophets of Judaism when he realized that “the terms, motivations, and concerns that dominate our thinking may prove destructive of the roots of human responsibility and treasonable to the ultimate ground of human solidarity.” Prophecy offers a redemptive alternative. It is the “exegesis of existence from a divine perspective.”

I look at the world from a secular vantage point. Prophecy and speculation over the supernatural means little to me, and I do not believe that a God moves through any speaker, even the most extraordinary. Heschel and Lischer’s theological arguments construct a helpful frame through which to look at certain moments, however, if one can take the questionable liberty of demystifying prophecy. Leaving differing beliefs in the existence of a divinity aside, perhaps one can argue that a prophetic moment is that which enables access to the highest truth of the human condition—the truth of universal human fraternity, the truth of suffering, and the redemptive power of love; the truth that has inspired much of religion, the best of art; the truth to which we aspire in our most magnificent moments. If it is possible to understand prophecy from that perspective, the 1988 Democratic Convention address from Jesse Jackson is the only moment in modern American history when prophecy conquered politics.

*

Mario Cuomo, the late governor of New York, is famous for his contention that an effective political leader “campaigns in poetry, but governs in prose.” Jackson’s rhetoric at the 1988 convention aspired to reach the heights of poetic grandeur. Its central ambition was to rescue the values of progressive unification around causes of justice from abstraction through their articulation in concrete terminology. He told a heartwarming story of his grandmother, and her tactics borne of privation and desperation, for keeping warm the children in her home:

When I was a child growing up in Greenville, South Carolina my grandmama could not afford a blanket. She didn’t complain, and we did not freeze. Instead she took pieces of old cloth—patches, wool, silk, gabardine, crockersack—only patches, barely good enough to wipe off your shoes with. But they didn’t stay that way very long. With sturdy hands and a strong cord, she sewed them together into a quilt, a thing of beauty and power and culture. Now, Democrats, we must build such a quilt.

Jackson transitioned from his homespun wisdom to the most important political battles of his time, many of them still ongoing, by identifying the isolated issues of social justice as “patches.” When workers fight for fair wages, Jackson thundered, they are right, but their patch alone is insufficient. When mothers petition for child care, equal pay, and paid family leave, they are right, but their patch is still too small. When Black people fight for civil rights, when Latino immigrants work toward an opportunity for citizenship, and when gays argue for equality, they are all righteous in their devotion, but their respective patches are not individually big enough.

“Be as wise as my grandmama,” Jackson advised, “pull the patches and the pieces together, bound by a common thread. When we form a great quilt of unity and common ground, we’ll have the power to bring about health care and housing and jobs and education and hope to our nation.”

Prophecy and speculation over the supernatural means little to me, and I do not believe that a God moves through any speaker, even the most extraordinary.

Like King making compassionate reference to the financial precarity he shared with his prison guard, Jackson identified common ground with class interest. Few within the Democratic Party spoke with adequate aggression against “Reganomics,” which Jackson defined as a set of policies based on the idea that “the rich have too little money, and the poor have too much.” In his address to the nation, he referred to the extreme income gains of the top 1 percent, along with the data indicating that the wealthiest Americans paid 20 percent less in taxes in the 1980s than they did in the 1970s. The middle class, working class, and poor, meanwhile, were slipping further away from domestic stability on a daily basis. Jackson implored his fellow Democrats that for the party to maintain a laudable and likable identity, it must believe in government as “a tool of democracy” working with the “consent of the governed” to improve living conditions for all Americans, but most especially those who live under the threat of illness, disability, poverty, or bigotry. After most politicians ignored rising inequality for decades, the few voices in the public square who warned of the dangers of austerity, and the destructiveness of policies giving advantage to the rich over everyone else, resound with greater prescience and profundity. The proposals of the Jackson candidacy—radical for their time and place, but pedestrian in Canada and Western Europe—are now those that dominate the platforms of most major Democratic Party leaders.

The speech soared not when Jackson spoke in the prose of politics, but when he offered the poetry of testimony. In his address, he is able to transcend the political and reach toward the prophetic. Not content to merely make a practical case for the poor, he advanced their dignity and asserted their humanity.

They work hard everyday. I know, I live amongst them. They catch the early bus. They work every day. They raise other people’s children. They work everyday. They clean the streets. They work everyday. They drive dangerous cabs. They change the beds you slept in in these hotels last night and can’t get a union contract. They work everyday. No, no, they’re not lazy. Someone must defend them because it’s right and they cannot speak for themselves. They work in hospitals. I know they do. They wipe the bodies of those who are sick with fever and pain. They empty their bedpans. They clean out their commodes. No job is beneath them, and yet when they get sick they cannot lie in the bed they made up every day. America, that is not right.

The United States is the only free and wealthy country that denies its people the most basic of human services. It is alone in the developed world in its cruelty toward the poor, forbidding them access to medicine when they are sick, threatening them with bankruptcy if they desire to take off work to care for a dying parent or spouse, burdening them with decades of debt for pursuing an education, and making their poorest children come of age in conditions of filth and infection.

Abuse, slander, and mistreatment of the poor is not only harmful public policy. It is a violation of the essence of democracy. Walt Whitman, writing in Leaves of Grass, identifies the “password primeval” and “ancient sign” of democracy among the “deformed persons . . . the diseased and despairing . . . the rights of those that others are down upon.” The great American bard prefaces his identification of the democratic voice with the promise, “I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.” Jackson sings in Whitman verse in his 1988 address; not only advocating for the humanity of the diseased and despairing but also affirming and advancing it in real time. Just as Whitman announced on the opening pages of his epic that every atom belonging to him as good, belongs to you, Jackson articulates something far beyond representation of the dispossessed, but political, social, and spiritual intimacy.

With a simple refrain—“I understand”—Jackson could separate himself from the other mere politicians and establish a familial and experiential kinship with his audience, beginning by broadcasting the criticism of skeptics:

“Jesse Jackson, you don’t understand my situation. You be on television. You don’t understand. I see you with the big people. You don’t understand my situation.” I understand. You see me on TV, but you don’t know the me that makes me, me. They wonder, “Why does Jesse run?” because they see me running for the White House. They don’t see the house I’m running from. I have a story. I wasn’t always on television. Writers were not always outside my door. When I was born late one afternoon, October 8th, in Greenville, South Carolina, no writers asked my mother her name. Nobody chose to write down our address. My mama was not supposed to make it, and I was not supposed to make it. You see, I was born of a teenage mother, who was born of a teenage mother. I understand.

I know abandonment, and people being mean to you, and saying you’re nothing and nobody and can never be anything. I understand.

Jesse Jackson is my third name. I’m adopted. When I had no name, my grandmother gave me her name. My name was Jesse Burns until I was 12. So I wouldn’t have a blank space, she gave me a name to hold me over. I understand when nobody knows your name. I understand when you have no name.

I understand. I wasn’t born in the hospital. Mama didn’t have insurance. I was born in the bed at the house. I really do understand. Born in a three-room house, bathroom in the backyard, slop jar by the bed, no hot and cold running water. I understand.

Wallpaper used for decoration? No. For a windbreaker. I understand. I’m a working person’s person. That’s why I understand you whether you’re black or white. I understand work. I was not born with a silver spoon in my mouth. I had a shovel programmed for my hand. My mother, a working woman. So many of the days she went to work early, with runs in her stockings. She knew better, but she wore runs in her stockings so that my brother and I could have matching socks and not be laughed at at school. I understand.

At 3 o’clock on Thanksgiving Day, we couldn’t eat turkey because momma was preparing somebody else’s turkey at 3 o’clock. We had to play football to entertain ourselves. And then around 6 o’clock she would get off the Alta Vista bus and we would bring up the leftovers and eat our turkey—leftovers, the carcass, the cranberries—around 8 o’clock at night. I really do understand.

“I had a life, an experience, that most of the others (politicians) did not, because American politics had become so caught up in the affairs of the wealthy. So, on a spiritual matter, I was simply trying to say, ‘I understand your pain, your difficulty, your challenges,’” Jackson told me when I asked about his refrain for the crescendo of his speech. “My grandmother almost did not vote for me,” he remembered, “Because she could not read or write. It was hard for her, because she would have to admit her illiteracy. So, I understand. It was simple.” Jackson continued with a practical application of his philosophy that still eludes most Democrats, especially those who in the aftermath of Trump immediately began to focus on the white working class—“Democrats were obsessed with regaining some of the votes of the white men who went to Reagan. I thought it more important to get those we never had, because they never registered, but were our natural allies, than scramble and make compromises for those we lost. That’s how Barack won in 2008. He brought out the rainbow.”

The speech soared not when Jackson spoke in the prose of politics, but when he offered the poetry of testimony.

As Jackson reaches his soaring conclusion in the speech, he addresses those whose voices society often places on mute, those who suffer through degradation, and those whose lives, both painful and heroic, are often without advocacy in the nexus of corporate media and major party politics. His voice rising in a full-throated shout, Jackson exercised the politics of friendship, and, in doing so, demands a friendship of politics. In a culture that too often evaluates worth and character according to the narrow and shallow metrics of wealth, glamor, and power, Jackson advanced a deeper alternative of universal beauty and sublimity.

In your wheelchairs. I see you sitting here tonight in those wheelchairs. I’ve stayed with you. I’ve reached out to you across our nation. Don’t you give up. I know it’s tough sometimes. People look down on you. It took you a little more effort to get here tonight. And no one should look down on you, but sometimes mean people do. The only justification we have for looking down on someone is that we’re going to stop and pick them up. But even in your wheelchairs, don’t you give up. We cannot forget 50 years ago when our backs were against the wall, Roosevelt was in a wheelchair. I would rather have Roosevelt in a wheelchair than Reagan on a horse.

As Jackson offers his homiletic helping of encouragement, the camera catches a man on the convention floor, sitting in a wheelchair. His face cracks into a half smile, but his eyes betray sadness. It is not presumptuous to imagine that Jackson’s words about “mean people” cut his heart like a scalpel. As soon as Jackson uttered the words, “look down on you,” the same man raises his thumb in the air. He never allows it to drop. Even as the crowd goes wild with Jackson’s comparison of FDR to Ronald Reagan, he keeps his arm extended, his thumb pointing toward the sky. It is in the coupling of Jackson’s words and that man’s facial expression and approving gesture that a politics of transcendence emerges, and through that emergence one gains an ability to accurately appraise the stakes of an argument. More than taxation, regulation, and even law, political debate can, in its most ambitious moments, raise the most crucial inquiries into what a society values. If we, as a people, would rather affirm the dignity of the man in the wheelchair than tacitly provide aid and encouragement to the mean people who look down on him, we must make a series of decisions, and those decisions must go beyond personal behavior and private charity. They must implicate the very essence of our society—how we organize our institutions, and how we exercise our power.

“Every one of those funny labels they put on you, those of you who are watching this broadcast in the projects, on the corners, I understand,” Jackson announced in a softer, more delicate enunciation. He then continued in the final emphasis of exactly what his campaign meant, and who it was meant for: “Call you outcast, low down, you can’t make it, you’re nothing, you’re from nobody, subclass, underclass; when you see Jesse Jackson, when my name goes in nomination, your name goes in nomination.”

__________________________________

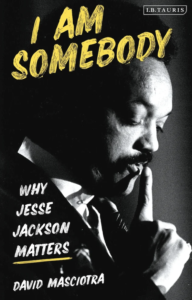

From I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters by David Masciotra. Used with the permission of I. B. Tauris & Company. Copyright © 2021 by David Masciotra.

David Masciotra

David Masciotra is a cultural critic, political commentator, and public lecturer. He is the author of five books, including Mellencamp: American Troubadour. He is a columnist with Salon, and has also written for the Washington Post, Atlantic, and Los Angeles Review of Books.