On the Gift (and Weight) of Winning a “Free” House

Anne Elizabeth Moore Considers the Cost of a House in Detroit

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

–Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

*Article continues after advertisement

For the cameras, I pretend that I am seeing it all for the first time. So one evening in early May 2016, families at dinner watch me on WXYZ-TV meandering hesitantly from room to room in the fancy outfit of an award recipient at her own celebratory gala, exclaiming with delight at: Empty white walls! Hardwood floors! A fancy bathtub! My own couch! That Nick and Nadine had carefully packed into a moving van in Chicago the previous day and driven for five hours before installing it in this mostly empty house and then leaving me alone to deal with the organization, the local artists, the new neighbors, the politicians, the print reporters, and the camera crews. The couch, years before, had been a gift from the same two friends, the castaway of a former lingerie designer. My friendship with Nick and Nadine spans over a decade, and the couch is ten times that old, roughly the same age as the building it now rests in.

My delight at the house, another gift, is unfeigned, even if the structure itself is more familiar than the camera crews portray for viewers at home. For ten years I have spent more time traveling than I have staying put, and I am tired and broke in a general way, although in the moment I feel happy, relieved, and excited. Those emotions are genuine.

So there’s me on TV, smiling and gesticulating exuberantly on the front steps of a cute little white bungalow in the BanglaTown neighborhood of Detroit, shaking the hand of the local city council member. He presents me with an award. Later he will let my calls about neighborhood needs go unanswered. One of the cofounders of the organization is also there. She hands me a set of keys. Soon she will be the cause of late-night phone calls and several emergency meetings. My next-door neighbors watch eagerly from their own porch. Within a day they will enter my home and explain to me that a neighbor, despite what I may have learned elsewhere, is a best friend.

Being awarded a house is both validating and terrifying, as well as several other emotions I find myself unable to affix.

There I am on video, standing between Casey Rocheteau, a poet and educator and the first free-house winner, and the poet Nandi Comer who, it is announced today, will receive the house after mine, making her the fourth free-house winner, and the only one from Detroit. Liana Aghajanian, an Iranian-American journalist and the second winner, is absent but sends greetings. Collectively, we soon come to share a secret: it can be a nightmare to be publicly awarded a free house.

*

Shortly before I move, I am on a train passing through Michigan in idle conversation with my seatmate. She is older than I am and suffers similar physical ailments, so we swap stories about medications and doctors between comments on the landscape.

“Where do you live?” she asks at one point.

“Chicago,” I tell her, “but I will move to Detroit soon.”

“Oh honey,” she says, patting my arm. “You’re not supposed to say Detroit. Call it Southeastern Michigan. Otherwise people will know.”

*

You will remember, perhaps vaguely, that an organization in Detroit started giving away free houses to writers in the mid-2010s—although you may recall instead that it was the city itself giving houses away, or that houses were being given to anyone who asked, or that all housing within the city limits of Detroit had been offered for free to anyone who wanted it, for any reason. Perhaps you heard that the city of Detroit tried to give free houses away, but that no one wanted them. None of that is true.

*

Legally, it is not my house, even after I move into it. My agreement with the organization stipulates a two-year residence before the title will go in my name. Still, it is called my house in several major newspapers, over the radio many times, on a variety of local newscasts, in international documentaries. My neighbors neither understand nor care about the nuance. To make it easier for everyone, I come to refer to it as my house. Although before I say it out loud, I always hesitate.

*

The first few years of my life, I should explain, are spent on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, home of the Sicangu Oyate, also known as the Sicangu Lakota. If you are lucky enough to live there as a white person, you learn quickly how easy it is to grow comfortable on stolen land, and how little governments give in compensation for that they take.

*

The word bungalow describes a small house with a low-pitched roof, usually only a single story tall, although sometimes one and a half or two. Houses of this design are marked by deep eaves and exposed rafters, an open floor plan, and built-in cabinetry. The term comes from the Hindi word bangla, meaning “belonging to Bengal.” The word was first used to describe the detached cottages built for early European settlers in India, hiding its inherent colonialism by paying homage to local culture.

*

For months, I am booked onto television and radio spots. I conduct email and telephone interviews. Two camera crews come by to film two different documentaries, one in French. Also I have a new book out, and conduct readings and interviews to promote it. Film options are discussed, agents consulted. It is an exciting time.

The history of the house suggests a municipal policy of violence against poor women that my media appearance and the public celebration of my supposedly free house neatly erases.

I am particularly looking forward to a live video feed for a morning news program in Chicago, where friends might see me as they prepare for work. I have been told that I am to be interviewed about both the house and the book. However, after the hosts greet me cheerily and explain to viewers that I have just won a free house for my writing, they do not ask me anything about what I write. Instead, they want to talk about Detroit.

“Aren’t all the houses free in Detroit?” the perky blonde says.

Her dark-haired male companion belly laughs. “Yeah!” he agrees. “What kind of a prize is that?”

*

Throughout a wayward young adulthood I seek solace in punk clubs, where I drink endless cheap beers out of cans with people who bathe rarely, wear leather, and have relationships with their parents as fraught as my own. This is where I first hear the phrase “property is theft,” a translation of French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s pronouncement, a vituperative argument against landowners who profit from renting out farmland and housing stock. Most often I hear it when someone grabs a beer that I protest is mine. “Property is theft,” some black-clad punk will say as he downs it.

*

Being awarded a house is both validating and terrifying, as well as several other emotions I find myself unable to affix. The plumbing inspector asks me about them one day, these emotions, and I tell him the exact same thing I’m telling you: being awarded a house brings about many diverse feelings. Not the least of them is surprise at the emotional complexity I am willing to display to the plumbing inspector, with little to no prompting.

*

The move begins the period where everyone quotes Virginia Woolf at me. They shake their heads in wonder and say something like, “Living the dream, right? A Room of One’s Own?”

I admit that I often scowl. At first I resent the association, because Woolf is a depressive, a modernist, and the only woman writer many who bring her up seem to have heard of. Then I begin to feel as if my situation—white girl in a Bengali Muslim neighborhood in a majority Black city—might appear colonialist enough without bringing an actual Brit into it.

*

Although I feign surprise at the new house for the cameras, in fact this day has been in the works for two years. Fakery disturbs me, both as a performer and as an audience member. Considering, however, that the keys I am handed unlock the doors of a house that will take another three and a half years to legally come into my possession, that I am told this house is free when in fact it will cost me close to $30,000 in repairs and legal fees—six times what the house originally cost the organization—and that the history of the house, invisible to me at the time, suggests a municipal policy of violence against poor women that my media appearance and the public celebration of my supposedly free house neatly erases, it is unclear to me what degree of complicity I hold in the sham.

_______________________________________

Excerpted from Gentrifier: A Memoir by Anne Elizabeth Moore. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Catapult Books. Copyright © 2021 by Anne Elizabeth Moore.

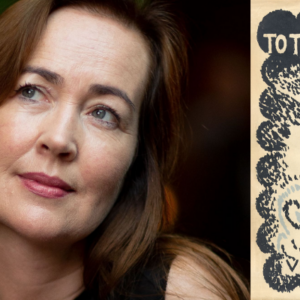

Anne Elizabeth Moore

Anne Elizabeth Moore was born in Winner, South Dakota. She has written several critically acclaimed nonfiction books, including the Lambda Literary Award–nominated Body Horror: Capitalism, Fear, Misogyny, Jokes, which was a Chicago Public Library Best Book of 2017, and Sweet Little Cunt, which won an Eisner Award. She lives in Hobart, New York, with her cat, Captain America.